Hyaluronan and heavy chains

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e3cbdafe-b08d-4f2f-877a-47af2b20b5dd/17-PUL-3682-Aronica-Hero-Image-650x450pxl_jpg)

17-PUL-3682-Aronica-Hero-Image-650x450pxl

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Despite our increased understanding of the pathobiology of airways inflammation and the development of biologics as a therapeutic tool in the treatment of severe asthma, we still have much to learn regarding the movement of inflammatory cells within the lung and the long-term consequences of chronic inflammation within the lung. Part of the answer may lie in the extracellular matrix.

Much of our understanding of inflammatory cell movement is based on the established roles of selectins, integrins and chemokines in trafficking cells from blood vessels to sites of inflammation. Though we know how these cells are moved, we don’t fully understand what happens when they do.

Hyaluronan (HA) is a glucosaminoglycan in which the disaccharide (glucuronic acid-beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine-beta-1,4-) is repeated several thousand times. HA is a major constituent of the extracellular matrix. Due to its very simple composition, physical properties and near ubiquitous distribution, for many years HA was considered to be inert scaffolding, having only a mechanical role in supporting and maintaining tissue structure — essentially a goo. However, findings over the last decade indicate that the role of HA is much broader than previously thought.

HA was first noted in the secretions of asthmatics in 1978, and HA levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of asthmatics have since been associated with severity of disease. Additionally, HA can be covalently modified during inflammation with the heavy chains (HCs) of inter-alpha-inhibitor (IαI) to form an HC-HA complex. We and others have shown that HC substitution of HA significantly increases leukocyte adhesion to HA, thereby potentially defining a mechanism through which HC-HA could direct inflammatory events in the asthmatic lung.

Advertisement

Our group’s research has revealed the importance of HA in inflammation and provided strong evidence for HA’s major role in providing the preliminary matrix necessary for collagen synthesis and fibrosis noted in asthmatic airways. We have shown that HA deposition is an early event in the lung, with detectable levels within 12 hours of the first antigen exposure. Our data also reveal that inflammatory cells colocalize in areas of HA deposition, suggesting a role for HA in maintaining and localizing inflammatory cells to sites of danger.

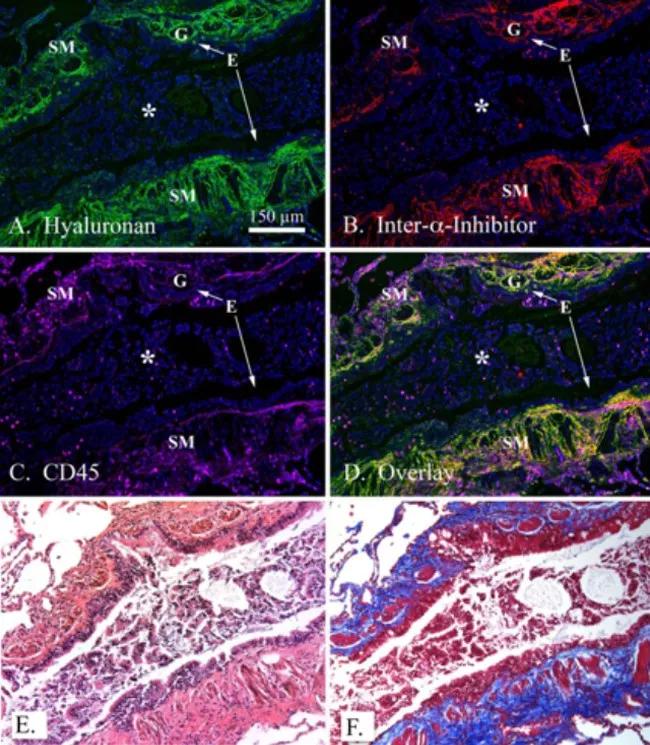

Although we completed much of this work in murine models of asthma, we also wanted to confirm that these findings and pathways are present in human asthma. We used immunofluorescent microscopy to examine the distribution of leukocytes within HC-HA matrices in lung tissue from three patients with acute severe asthma. (Figure). The airways of these patients displayed significant smooth muscle proliferation, epithelial metaplasia, mucus gland hypertrophy and airway obstruction due to mucus plugging (E,F). HA was distributed throughout the submucosa region and distributed around, but not within, serous mucus glands (A). Furthermore, HA was largely absent within the mucus of the airway lumen. IαI (i.e., HC) distribution was almost exclusively present in the submucosa region, displaying a striking colocalization with HA indicative of pathological HC-HA matrices (B). Using the common leukocyte antigen CD45 as a generic marker of inflammatory cells, we found large numbers of leukocytes in the submucosa region of these lungs colocalizing with and embedded within pathological HC-HA matrices.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/bdb912ec-e557-43b2-864c-13088ddc2e35/Aronia-inset_jpg)

Colocalization of leukocytes within HA matrices modified with heavy chains in asthmatic airways. A paraffin lung section of a patient with acute severe asthma was probed with a hyaluronan binding protein (green; A), an antibody against IαI (red; panel B) and the common leukocyte antigen CD45 (panel C; magenta). DAPI stained nuclei are shown in blue. Overlay is shown in panel D. H&E and trichrome staining from the same region shown in panels A-D are shown in panels E and F, respectively. Magnification is 10x. A magnification bar is portrayed as a white line in panel A (150 μm). The airway epithelium is identified by an E, airway smooth muscle by SM, submucosal glands by G and a mucus plug by an asterisk in panels A-D. These images were representative of three asthmatic replicates. Figure and legend originally appeared in J Biol Chem. 2015;290(38):23124-34. © American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.]

In summary, we believe that the extracellular matrix, an often ignored component in many diseases, is an active and direct participant in inflammatory processes including asthma, and a better understanding of these mechanisms may lead not only to insights into these processes but also to novel treatment pathways.

Dr. Aronica is staff in the departments of Pulmonary Medicine, Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and Pathobiology

Advertisement

Advertisement

Takeaways from the most recent annual meeting centered around clinical advances, AI integration and professional development

Recent breakthroughs have brought attention to a previously overlooked condition

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Looking at the real-world impact and the future pipeline of targeted therapies

The progressive training program aims to help clinicians improve patient care

New breakthroughs are shaping the future of COPD management and offering hope for challenging cases

Exploring the impact of chronic cough from daily life to innovative medical solutions

How Cleveland Clinic transformed a single ultrasound machine into a cutting-edge, hospital-wide POCUS program