Adding tissue from the cheek to achieve improved outcomes

In order to achieve improved cleft palate repair outcomes, Cleveland Clinic craniofacial surgeons Antonio Rampazzo, MD, PhD, and Bahar Bassiri Gharb, MD, PhD, have further refined an established but little-used technique: The addition of myomucosal tissue from the patient’s cheek to facilitate closure of the palate. This reduces tension and lengthens the palate, thereby improving speech outcomes.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The addition of buccal myomucosal flaps to the Furlow double opposing Z-plasty palatoplasty technique was first described in 1997 by Robert J. Mann, MD, of Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Yet, the procedure still isn’t widely practiced due to added complexity to the palate repair.

The Furlow Z-plasty itself, commonly used for the past few decades, represented a major advance over older techniques because it provides significant improvement in velar muscle repositioning and lengthens the palate, resulting in less risk for postsurgical velopharyngeal insufficiency.

But, Dr. Rampazzo says, despite those advantages the Furlow technique still doesn’t involve sufficient tissue for complete cleft palate repair, especially with wider clefts. “When you leave areas open they will develop scar tissue and contractures and shorten the palate. That’s what we’ve been doing.”

In contrast, the addition of buccal myomucosal flap tissue allows for closure of the palatal cleft with minimal tension and reduced scar risk. The amount of tissue harvested from the cheek depends on the size of the cleft. “Some cleft palates have very little tissue. We add the tissue as we go. We start with a standard repair, then with tension we add tissue.” he explains.

Mann’s 2017 retrospective review of 489 patients who had all been treated with the double opposing Z-plasty showed equally good surgical outcomes and nasal resonance scores among 319 patients with wider clefts who also received the buccal myomucosal flap approach as with those who had narrower clefts.

Advertisement

Going a step further, Drs. Rampazzo and Bassiri Gharb use buccal flaps in nearly all cleft palate repairs, not just wider ones, noting “We have a very low threshold to use them also in narrower clefts,” because they see better outcomes across the board.

There are some downsides, he acknowledges. “It is technically difficult. You need microsurgery experience.” It also takes more time, about 35 minutes to an hour per flap. But, he says that surgeons shouldn’t be concerned that the tissue will die, since that doesn’t typically happen. “It’s a very safe procedure.”

With Cleveland Clinic’s most recent 11 primary cleft palate patients, all aged one year or younger, Drs. Rampazzo and Bassiri Gharb have further refined the buccal flap procedure by locating the small vessels going into the cheek and dissecting them out in order to bring the tissue even farther into the palate for a better reconstruction.

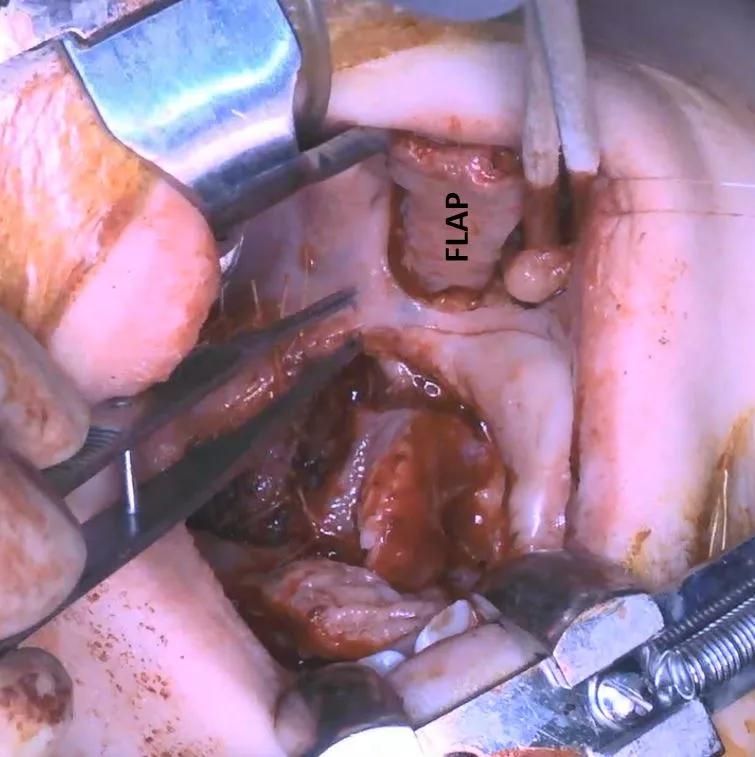

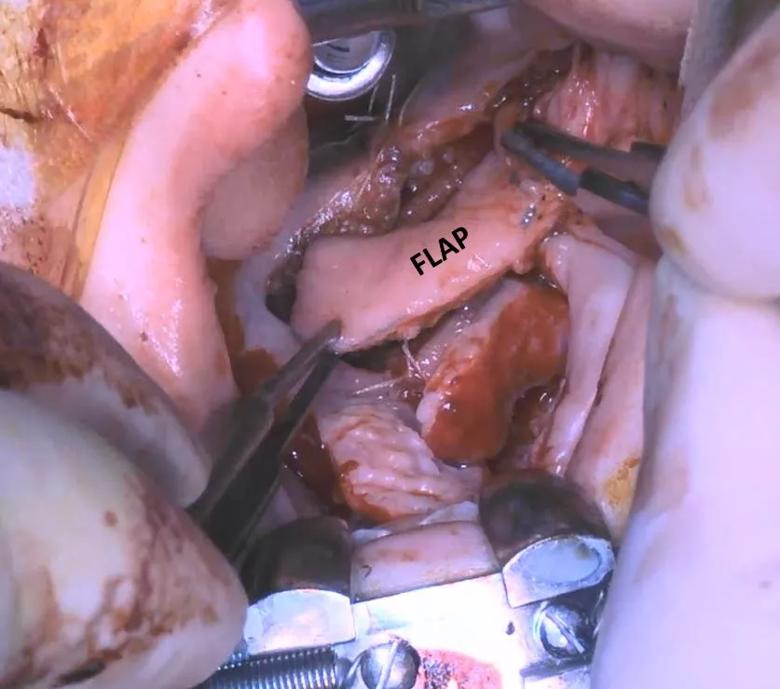

“We identify the buccal vessels and we island the flap (figure 1). This allows a greater mobilization of the buccal myomucosal flap and we don’t need a second stage to divide the pedicle of the flap (figure 2). Overall this way we decrease the incidence of oronasal fistulas and we hope to decrease the velopharyngeal insufficiency and avoid a speech procedure when the child is older,” Dr. Rampazzo explains.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/05b349c9-7eda-4706-b36a-a174c98dd703/figure-1_jpg)

Figure 1. The buccal myomucosal flap was harvested from the cheek.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2b042784-ca46-4359-9833-857363492ad6/figure-2_jpg)

Figure 2. The buccal myomucosal flap was advanced into the palate to reconstruct the soft tissue defect.

This “islanding” technique was made possible by the availability of Cleveland Clinic’s anatomy laboratory, he notes. “We are lucky because we have an anatomy lab where we can do cadaveric studies first on the vascular anatomy. We went to the cadaver lab first, and injected dye to help us understand the anatomy of the vessels to use the technique in these babies. That was very helpful for us.” He presented those results earlier this year at the Plastic Surgery Research Council meeting.

Advertisement

Preliminary results for the 11 patients – all operated on within the past year and a half – look very good, with no fistulas. “They’re starting to speak very well, but we have to wait until they’re 4 to 5 years of age when their speech is more developed to be sure,” Dr. Rampazzo says.

If the long-term outcomes prove the value of the buccal flap with islanding procedure, he hopes more surgeons will adopt it despite its technical difficulty. “I truly believe it’s the way to go to repair cleft palate. It’s a great technique.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Family history may eclipse sun exposure in some cases

Consider secondary syphilis in the differential of annular lesions

Persistent rectal pain leads to diffuse pustules

Two cases — both tremendously different in their level of complexity — illustrate the core principles of nasal reconstruction

Stress and immunosuppression can trigger reactivation of latent virus

Low-dose, monitored prescription therapy demonstrates success

Antioxidants, barrier-enhancing agents can improve thinning hair