When no source can be found, suspect infective endocarditis

An 11-year-old patient of tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia, with previous cardiac surgeries, presented with three days of intermittent fevers ranging from 37.7 to 38.6°C who defervesced with acetaminophen and ibuprofen.* There was no history of rhinorrhoea, cough, chest pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, burning micturition, myalgia, joint pain or skin rash.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

His most recent cardiac intervention was dilation of the left pulmonary artery stent at 6.5 years of age and his most recent echocardiogram three months prior revealed moderate stenosis with maximal transvalvular flow velocity of 2.4 m/second across the valved glutaraldehyde-fixed bovine jugular vein graft (Contegra, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) and moderate regurgitation.

His vital parameters revealed the following: heart rate, 100/minute; blood pressure, 118/69 mmHg; temperature, 37.8°C; oxygen saturation, 100%; and his clinical examination revealed grade 2/6 systolic murmur in the left parasternal space. The clinician ordered complete blood count, urine analysis and blood culture studies that revealed a white blood count of 7,400/mcL with 85% neutrophils and normal urinalysis. He was discharged home with a presumptive diagnosis of viral fever.

His blood culture study results revealed Streptococcus gordonii after 48 hours. He continued to have intermittent fevers responsive to antipyretics in that time period. He was admitted to the hospital and his repeat blood culture study revealed S. gordonii. His detailed clinical examination did not reveal a new cardiac murmur, any peripheral stigmata of infective endocarditis, or a specific focus of infection. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an increase in the stenosis of the Contegra conduit with a maximal transvalvular flow velocity of 3.5 m/second, severe regurgitation with diastolic flow reversal in the branch pulmonary arteries, and an 8 × 5mm mobile vegetation within the conduit. He was diagnosed as a “definite” case of infective endocarditis of the Contegra conduit and initiated on a six-week course of antibiotics with good response.

Advertisement

“Had we not been proactive and pursued a source of fever in this patient, we would’ve missed the diagnosis,” says Hemant S. Agarwal, MD, MBBS, a pediatric cardiac intensivist in the department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine at Cleveland Clinic Children’s and senior author on the case studies recently published in Cardiology in the Young.

A 10-month-old infant with unbalanced atrioventricular canal defect and gastrooesophageal reflux disease with previous cardiac and gastrointestinal surgeries presented with gastro-jejunal tube leakage and tactile warmth.* There was no history of rhinorrhoea, cough, vomiting, diarrhoea or irritability. She had undergone bidirectional Glenn shunt at 4.5 months of age and her most recent cardiac intervention included balloon dilation of the neo-left pulmonary artery stenosis at 7 months of age. Her most recent echocardiogram two months prior revealed unobstructed laminar flow in the Glenn pathway, with some narrowing in the neo-left pulmonary artery, mild right and left atrioventricular valve regurgitation with normal right ventricular systolic function.

Her vital parameters revealed: heart rate, 164/minute; blood pressure, 114/72 mmHg; oxygen saturation, 74%; and rectal temperature, 38 °C. Her clinical examination revealed erythema associated with formula leakage around the gastrostomy skin site. The clinician ordered a complete blood count, serum chemistry, blood culture studies, and the patient was admitted to the hospital. Her studies revealed a white blood count of 12,200/mcL with 66% neutrophils and normal serum chemistry. Her gastro-jejunal tube leakage was corrected and enteral feeds were resumed.

Advertisement

She developed another fever spike of 38°C in the next 24 hours. Her initial blood culture study results revealed Enterococcus fecalis. A repeat blood culture study undertaken after the second fever spike also revealed E. fecalis. Her urine culture was negative for organisms and her clinical examination did not reveal a new cardiac murmur, any peripheral stigmata of infective endocarditis or a specific focus of infection. A transthoracic echocardiogram study revealed unobstructed laminar flow in the Glenn pathway with similar degree of neo-left pulmonary artery narrowing, mild right and left atrioventricular valve regurgitation, and a 7 × 4mm mobile vegetation attached to the crux of the heart close to the left atrioventricular valve. She was diagnosed to have “definite” IE and initiated on a six-week course of antibiotics with a good response.

Children with CHD are at significantly higher risk of developing infective endocarditis. Although the overall incidence of infective endocarditis in children is 0.43 per 100,000 children, the incidence in children with CHD is much higher – at 6.1 per 1,000 according to one study.

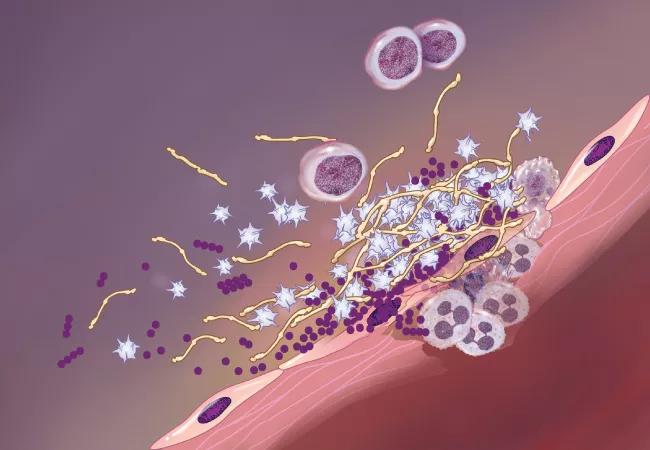

In children with CHD, infective endocarditis is the result of an injury to the endocardial surface caused by increased turbulence. While initially noninfectious, transient bacteria or fungi adheres to the injured endocardium and thrombus, which can proliferate rapidly. Additionally, “any type of foreign material, such as synthetic material, increases the risk of infection,” says Malek Yaman, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s.

Advertisement

“Infective endocarditis can be an easy diagnosis to miss if you’re not looking for it,” Dr. Agarwal notes. “Infective endocarditis can be insidious.”

Additionally, identifying a new heart murmur in a child who has had previous surgical intervention may be difficult, and making the diagnosis requires serial blood cultures and a positive echocardiogram. There are no other lab tests or inflammatory markers to indicate infective endocarditis. For this reason, it is very important to get that initial blood culture on a patient with CHD who presents with a fever for which you can identify no source, according to Dr. Agarwal.

Complications of infective endocarditis include valvular insufficiency, stroke, infarction of the kidneys or other organs, metastatic infection or systemic immune reaction (glomerulonephritis). Infective endocarditis can also lead to the development of abscesses inside the heart that may need to be surgically drained.

Assuming no complications, patients with infective endocarditis are treated with a six-week course of intravenous antibiotics and serial echocardiograms, and tend to be discharged in less than one week. “Indications for surgical intervention are also evolving” according to Dr. Yaman. “In cases that are hemodynamically unstable or refractory to medical treatment, we have a lower threshold for considering surgery as surgical techniques and outcomes have markedly improved.”

“When detected and treated early, infective endocarditis generally responds well to intravenous antibiotics. We should never ignore fever in children with congenital heart disease. If physicians are unable to pinpoint the source of the fever, we should have a high level of suspicion and not send the patient home without further workup,” concludes Dr. Agarwal.

Advertisement

*Please note: Case studies republished with permission from Cardiology in the Young. This work was originally published here: DonaireGarcia A, Burke B, Latifi SQ and Agarwal HS. Fever without a source in children with congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2020 Sep;30(9):1353-1355.

Advertisement

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management

A closer look at the impact on procedures and patient outcomes

Experts advise thorough assessment of right ventricle and reinforcement of tricuspid valve