Dr. Heather Gornik takes issue with new draft recommendation

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6d3eb254-a41c-4a92-9038-3b0861714e38/18-HRT-116-USPSTF-Persp-CQD-Feat-2_jpg)

18-HRT-116-USPSTF-Persp-CQD-Feat-2

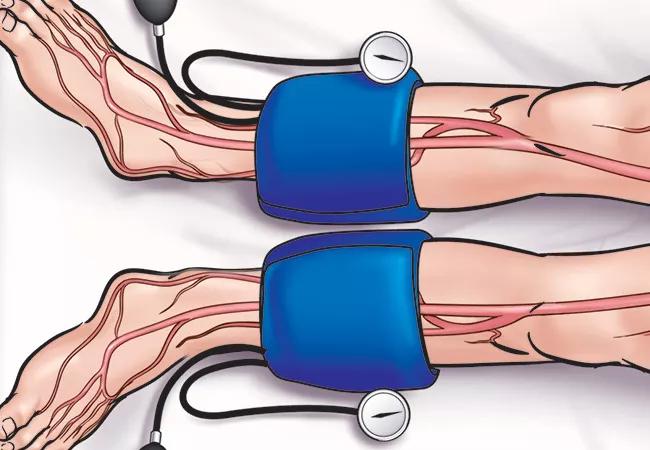

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) will soon issue final recommendations on use of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) for screening and risk assessment for peripheral artery disease (PAD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in asymptomatic adults. Based on the USPSTF’s final draft, released in January, the recommendation is likely to be negative.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In the U.S., a low ABI (typically ≤ 0.9) is considered diagnostic for PAD, especially in the presence of symptoms. Although the USPSTF found adequate evidence that the ABI is accurate in detecting PAD in patients with symptoms, it found insufficient data on the index’s accuracy in identifying asymptomatic people who could benefit from treatment for PAD or CVD.

While the USPSTF determined that direct harm from obtaining the ABI is minimal, it said possible harms arising from false-positive results include exposure to imaging risks for confirmation of a PAD diagnosis, anxiety and adverse effects from treatments (e.g., bleeding with aspirin or diabetes with statins). The USPSTF’s assessment does not consider the costs of providing the service.

Consult QD asked PAD expert Heather Gornik, MD, a cardiologist and President of the Society for Vascular Medicine, for her take on the USPSTF draft statement.

Q: What do you think of this draft recommendation against use of the ABI for detecting PAD in asymptomatic adults?

A: PAD is a common medical problem in older people with atherosclerotic risk factors and is associated with increased cardiovascular risk as well as impaired walking abilities. PAD is woefully underdiagnosed and underrecognized, even among patients with significant disease.

Patients may be “asymptomatic” because their PAD has limited their ability to walk, so that they walk less than they used to. Unfortunately, limiting ABI testing to only those patients with classic symptoms of claudication or limb ischemia is problematic, as most people with PAD have no symptoms or have leg symptoms that are atypical for claudication or may just have walking impairment. Patients with classic claudication are only the tip of the iceberg for this disease.

Advertisement

Q: How do you recommend that the ABI be used?

A: Patients who don’t have classical claudication but who have pulse deficits or bruits on physical examination should undergo ABI testing to confirm the diagnosis of PAD regardless of whether they have symptoms. The same goes for patients who have “atypical” leg symptoms or any report of difficulty with walking.

I was vice-chair of the writing committee for the 2016 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guideline on management of patients with lower-extremity PAD. We strongly recommended ABI testing in patients with history or physical exam features suggestive of PAD (class I). Also, we advised that ABI testing is reasonable (class IIa) for patients at risk for PAD, including those with atherosclerotic risk factors or known coronary artery disease, even without signs or symptoms of PAD.

Q: What’s your response to the USPSTF’s assessment of potential harms from the ABI?

A: Most patients with PAD are managed with medical therapies, particularly antiplatelet agents and statins, and we now have supervised exercise therapy as an option for Medicare beneficiaries. We also have good guidelines that don’t support unnecessary imaging or invasive procedures for these patients.

The ABI is a very simple test that can be done in the office with a blood pressure cuff and a handheld Doppler device by a trained nurse or medical assistant or of course a physician. Even when performed in a vascular lab with higher-tech equipment, it’s still a relatively low-cost procedure involving very low to no risk.

Advertisement

An abnormal ABI has a very high positive predictive value. There are very few false positives, so it doesn’t require additional confirmatory testing to establish the diagnosis of PAD. Sometimes false-normal ABI results occur in cases of diabetic vascular disease or chronic kidney disease, but this would be rare in an asymptomatic patient.

Q: What additional information might help close knowledge gaps in this area?

A: A Danish study published in The Lancet in November 2017 found a mortality benefit from a screening program for PAD, as well as for abdominal aortic aneurysm and hypertension, that included ABI screening. These are interesting data that show a potential impact for detecting patients with PAD and modifying their cardiovascular risk, but we still need more data. I’d like to see additional trials focused specifically on the ABI and identifying undiagnosed PAD.

I’d also like to see more randomized controlled trials of medical therapy to prevent cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, and limb events (including acute ischemia, need for revascularization and amputation) among patients with PAD who are “asymptomatic” or who have walking impairment but don’t have classical claudication.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Initial data indicate tolerability and promising cardiac remodeling effects

LLM-driven system uses both structured and unstructured data, provides auditable justifications

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most