The evidence, the obstacles, and the opportunity to improve care

Regionalization of congenital heart surgery (CHS) centers has the potential to improve quality of care and outcomes while potentially reducing costs. Many European countries and Canada have accomplished it, but in others, including the United States, significant obstacles still must be overcome.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

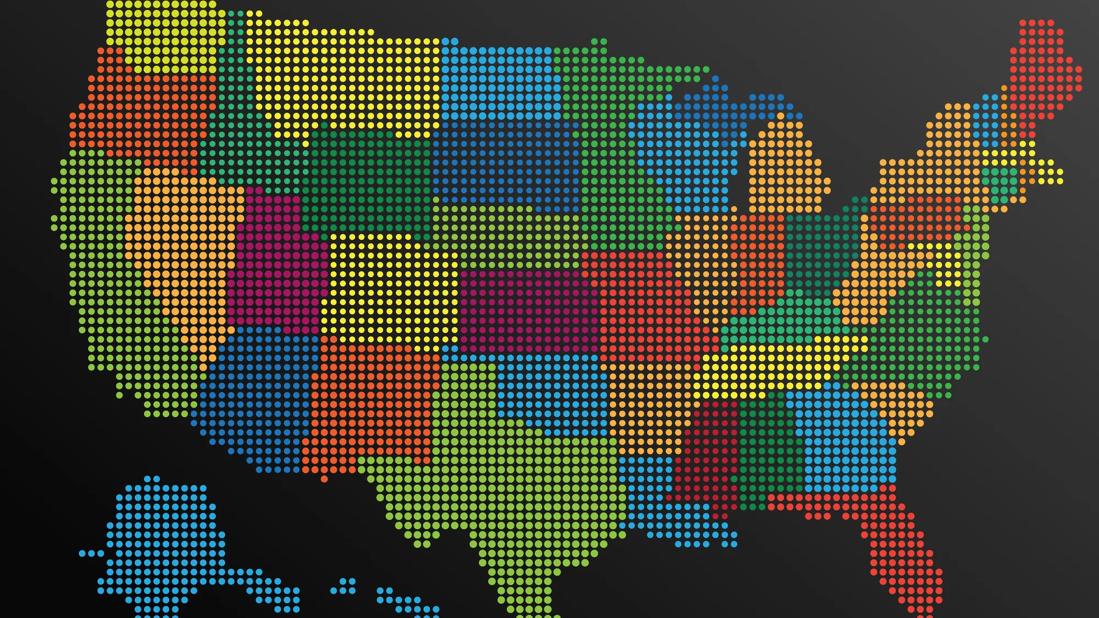

The United States currently has an excess of CHS programs that are clustered in certain geographic regions, creating redundancy. In a 2019 study, at least 153 CHS hospitals were identified in the US, of which 66% were located within 25 miles of another center. Surgeon caseloads at some of these centers are relatively low, leading to great variation in both short- and long-term outcomes and costs.

“Data show that if we increase surgery center volume we will improve survival, especially in complex care,” says congenital and pediatric heart surgeon Tara Karamlou, MD, MSc.

In a recent review paper published in Current Opinion in Cardiology, Dr. Karamlou and co-authors outline the potential benefits to consolidation of low-volume and unequally distributed centers into fewer high-volume, high-quality tertiary / quaternary institutions, along with streamlining supply chains, referral networks, and practice patterns. They also discuss the challenges and suggest possible models and roadmaps for overcoming the barriers to regionalization in the U.S. and the developing world.

“In the United States, it’s going to take an alignment of incentivization. We have an incentive-based healthcare delivery system. That might not necessarily be aligned with regionalization initiatives, which may triage certain complex cases to centers of excellence,” Dr. Karamlou points out.

In contrast, in many low- and middle-income countries there are too few CHS programs. About 90% of newborns in these areas with congenital heart defects — about 150,000 a year — simply die, typically without having had a prenatal diagnosis.

Advertisement

As some of these countries are only now starting to develop CHS services, “we need to have some way to extend to them a more pragmatic way to structure things so they don’t end up like us, where we’ve got these excess centers. I think that they can develop pathways using a much more data-driven standard,” she says.

“We’re trying to develop focus groups in conjunction with some of the policymakers in those countries to help us arbitrate and devise these types of healthcare delivery paradigms.”

One concern often expressed regarding regionalization is that it could potentially reduce geographic access for some individuals. But in fact, data from Cleveland Clinic researchers suggest that strategic placement of the centers would not substantially affect patient travel distance but would reduce in-hospital mortality.

A 2020 simulation that Dr. Karamlou co-authored suggested that if all CHS in the United States were done in programs that perform a minimum of 300 cases annually, 116 lives could be saved each year.

Such regionalization could be accomplished with two types of models. One, the “Hub-and-Spoke,” relies on a hospital or set of hospitals (“hubs”) that offer a full set of complex and comprehensive CHS procedures, while secondary centers (spokes) provide lower-complexity operations and refer back to the hubs. Such models have been implemented in Sacramento Valley, California and in Canada and Mexico.

The other model, the distributed or “tiered” model, relies on establishment of “centers of excellence” and “comprehensive centers of excellence” that work independently or in partnership. Criteria and accreditation for these have recently been developed by the Adult Congenital Heart Association.

Advertisement

Still to be determined, Dr. Karamlou says, is the optimal threshold by which patients would be potentially triaged away from smaller volume programs to larger volume programs. She and co-author Karl F. Welke, MD, of Atrium Health Levine Children’s Hospital, Charlotte, North Carolina, will be investigating that question this year.

As for the fear of losing revenue, Dr. Karamlou and colleagues point to the current evolution in medicine toward prioritizing value-based care over purely profit-driven models. And, she notes, in some cases regionalization might be based on performance rather than volume.

“We shouldn’t necessarily mandate it based on volume threshold. It could be based on quality metrics, for example. People have used volume because it’s easy to measure and is considered a surrogate for quality, but we would argue that regionalization might be based on quality metrics that all centers can agree upon. Can we provide the same quality at lower cost?”

In the paper, Dr. Karamlou and colleagues also flip other regionalization challenges into opportunities, including improving medical training via higher-volume centers and changing state laws to encourage regionalization based on volume thresholds, such as has begun in Florida.

“Although CHS programs may provide a considerable source of revenue for tertiary and quaternary hospitals, patients’ welfare should remain at the core of any healthcare delivery consideration,” Dr. Karamlou and colleagues conclude.

Advertisement

Advertisement

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management

A closer look at the impact on procedures and patient outcomes

Experts advise thorough assessment of right ventricle and reinforcement of tricuspid valve