Early screening, first-line therapy choice critical

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/64fdc01c-fb7a-49cf-9caf-226f29da66d3/19-CNR-766-Uveal-melanoma-650x450-1_jpg)

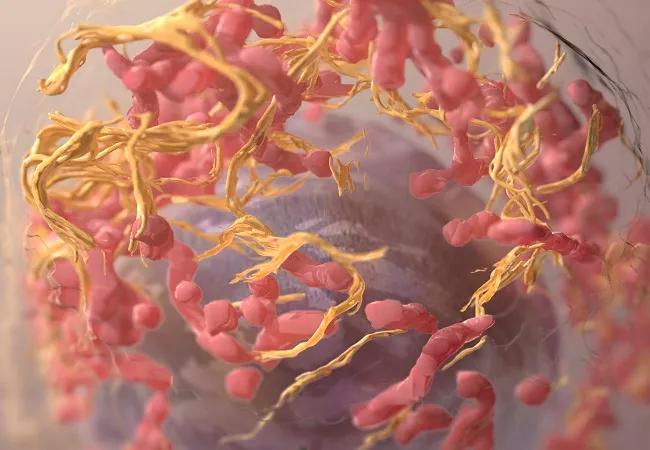

3D structure of melanoma cell

Patients with uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver who present without symptoms and receive local therapy as first-line treatment have longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than those who present with symptoms and receive other first-line therapies.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Those are the main findings of a study of Cleveland Clinic patients recently published in Ocular Oncology and Pathology.

Uveal melanoma is an intraocular malignancy that originates in melanocytes in the iris, choroid or ciliary body. Its incidence in the United States is 5.2 cases per 1 million population per year. Roughly half of patients develop metastatic disease.

“This rare cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and typically carries a poor prognosis,” says Arun D. Singh, MD, Director of the Department of Ophthalmic Oncology at Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute and a co-author of the report. “In this study we sought to determine what factors, if any, lead to better outcomes for these patients.”

Researchers performed a retrospective study of 73 patients with uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver seen at Cleveland Clinic between 2004 and 2016 (median age 63 years). More than half of patients (58%) had uveal melanoma located in the choroid. Episcleral plaque brachytherapy was the most common treatment (52%), with enucleation at 47% and one patient receiving proton beam radiation for the primary tumor (uveal melanoma).

On average, liver metastasis occurred 27 months after uveal melanoma diagnosis (interquartile range 13-46 months). Overall median PFS was four months (95% confidence interval [CI] 3-5 months), and OS was 15 months (95% CI 11-18 months). Upon multivariate analysis, patients who were diagnosed by symptoms (N = 10) had a much higher risk of mortality (hazard ratio 2.39, p < 0.017), with an OS of seven months compared with 16 months for patients who were asymptomatic at diagnosis (p = 0.005).

Advertisement

Treatment with checkpoint inhibitors did not improve average survival outcomes, although median follow-up was shorter in that group.

“This finding underscores the importance of screening patients at risk,” says Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center medical oncologist Pauline Funchain, MD, lead investigator on the Gross Family Melanoma Registry and a co-author of the study. “The best treatment for any cancer is early detection. Small uveal melanomas are known to have less metastatic potential. We are the only U.S. center with a familial melanoma registry that aims to identify individuals at high risk for developing melanoma with the goal of developing better surveillance and treatment strategies.”

Using data from this registry, Dr. Funchain and team have developed a clinical trial testing PARP inhibition combined with immunotherapy in the treatment of uveal and other metastatic melanomas.

This study confirmed the superior efficacy of local therapy as first-line treatment, as previously demonstrated in a 2016 study conducted by Dr. Singh and Eren Berber, MD, Director of Robotic Endocrine Surgery at Cleveland Clinic’s Endocrinology & Metabolism Institute and a coauthor of the 2019 study. In addition to significantly longer PFS and OS, more than 90% of patients in the 2019 study had no extrahepatic metastasis, compared with 64% of those treated with systemic therapy. All six patients who lived longer than three years were in the local treatment group. Two of them are still alive as of early 2020.

Advertisement

Drs. Singh and Berber conducted the 2016 study with colleagues in Cleveland Clinic’s Cancer Center and Digestive Disease & Surgical Institute. Researchers found that long-term survival is possible in patients with uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver who have a long interval to metastases development and limited liver tumor burden and who receive laparoscopic surgical resection. It was the first published report on the results of laparoscopic surgery for hepatic metastasis from uveal melanoma.

“We have a multidisciplinary team of specialists approaching uveal melanoma from all angles,” says Dr. Singh. “In addition to the aforementioned studies, we have also reported on our experience using hepatic ultrasonography to monitor and confirm liver metastases in a noninvasive manner, as well as exploring potential biomarkers for more accurate prognosis and monitoring. We are continually incorporating our research findings into our clinical approach.”

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center serves as a referral center for a variety of rare cancers and blood disorders, and its ocular oncology program treats patients with uveal melanoma, retinoblastoma, retinal cancer and others. Medical professionals who want to refer a patient should complete the online cancer patient referral form.

Feature image: 3D structure of a melanoma cell derived by ion abrasion scanning electron microscopy.

Credit: National Cancer Institute

Advertisement

Advertisement

Goal-of-care discussions drive earlier hospice access

Clinical trials and de-escalation strategies

Combination therapy improves outcomes, but lobular patients still do worse overall than ductal counterparts

Bringing empathy and evidence-based practice to addiction medicine

Supplemental screening for dense breasts

Combining advanced imaging with targeted therapy in prostate cancer and neuroendocrine tumors

Early results show strong clinical benefit rates

The shifting role of cell therapy and steroids in the relapsed/refractory setting