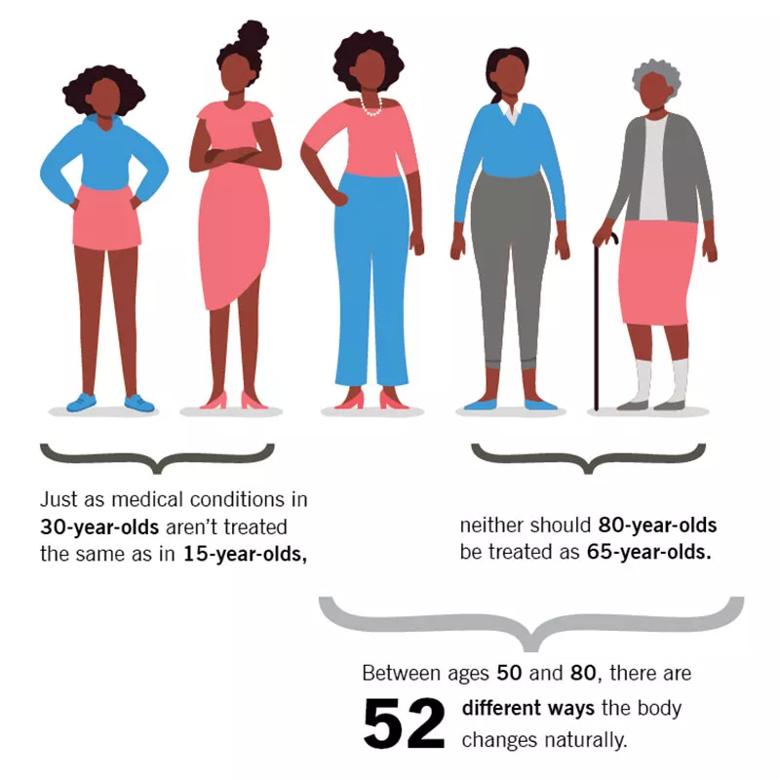

Age-related pathophysiologic changes warrant special clinical consideration

A recent review of COVID-19 presentations and treatment strategies in geriatric patients highlights the atypical symptoms and unique challenges that can complicate the management of older adults. In an article published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic geriatricians Saket Saxena, MD, and Ardeshir Hashmi, MD, emphasize the need for a modified approach when diagnosing and treating COVD-19 in patients older than 65, who face a disproportionately greater risk of severe illness and death. The authors further explain that the pathophysiologic changes that accompany aging and the cumulative impact of chronic comorbidities can compound these dangers.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Fever: Mean body temperature decreases with age, giving older patients a lower baseline temperature. A fever of 38.3°C (101°F) or higher in geriatric patients implies serious infection and warrants immediate attention. The Infectious Disease Society of America defines fever in older adults as a single oral temperature over 37.8°C (100°F), two oral repeat readings over 37.2°C (99°F) or an incremental increase of 2°F over baseline temperature. As such, fever may be an insufficient determinant of COVID-19 in geriatric patients, especially those who are frail.

Cold and cough symptoms: It is difficult to differentiate an acute cough or shortness of breath in older adults with chronic lung conditions. Loss of taste or smell is also difficult to differentiate in older patients, many of whom suffer from sensory impairments. Fatigue and body aches, which are also common in this population, are nonspecific. Minor symptoms, including sore throat, new-onset congestion, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea may be more valuable diagnostic indicators.

Delirium or altered mental status as a symptom: Age greater than 75, residence in an assisted living facility or nursing home, prior use of psychoactive medication, hearing and vision impairment, stroke and Parkinson’s disease appear to be predictive of delirium. Although current guidance does not include delirium as a diagnostic symptom of COVID-19, hospital strategies for managing the disease (eg, restricting visitors, isolation, personal protective equipment for caregivers, physical and chemical restraints) can contribute to disorientation and increase patients’ risk of developing delirium, leading to poor outcomes and mortality.

Advertisement

Falls, frailty and anorexia: Frailty and pre-frailty, as characterized by a simple frailty scale, are associated with increased COVID-19 severity. Of note, frailty may also be linked to lower lymphocyte counts (specifically, lower CD8+ counts), illustrating the interplay of frailty, immunosenescence and COVID-19. In those older than 85, falls and sudden or new-onset fatigue should be considered a symptom of illness.

Anorexia can lead to dehydration and failure to thrive in older adults and remains an important presentation of COVID-19.

Prognostic indicators: C-reactive protein peaks and lymphocyte nadirs are independent serological predictors of death, as are shortness of breath and oxygen desaturation in the oldest COVID-19 patients. Male sex, a history of cardioneurovascular disease, low albumin, serum creatinine and elevated troponin and brain natriuretic peptide levels are additional predictors of death in this patient population.

An estimated 40% of older COVID-19 patients have no radiographic abnormalities.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/02397575-3233-4834-a3ad-8ba89ba28c1b/21-GER-2517656-CQD-Inset-800x800-1_jpg)

Hospitalized older adults with delirium: Delirium during hospitalization is closely related to mortality and poor functional outcomes in older adults. Furthermore, pharmacological management of delirium in the elderly can have significant adverse effects and is only advised for those at risk of self-harm. The Hospital Elder Life Program is an entirely nonpharmacological-based prevention strategy shown to significantly decrease delirium by improving the management of cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, dehydration, visual and hearing impairment, and immobility.

Advertisement

Strict lockdown measures for residents of residential care facilities often lead to social isolation and related depression, anxiety, worsened dementia and delirium. Clinicians should be cognizant of these challenges and avoid attempting a “quick fix” by prescribing potentially inappropriate medications. Altered circadian rhythms, which can be caused by staying indoors extensively, can also trigger delirium and deplete the physiological reserves needed to fight infection.

Patients with dementia and COVID-19: The pandemic has been particularly daunting for older patients with moderate to advanced cognitive impairment. The “double hit” of COVID-19 and dementia has made it difficult to consistently implement public health measures like social distancing, mask wearing and hand hygiene. In addition, personal protective equipment and restricted visitation policies can be disorienting and scary for elderly patients. The increased behavioral manifestations that have been caused by this milieu have placed an additional strain on patients with dementia and their families.

Multidisciplinary care: Successful geriatric care is multidisciplinary by nature. Physicians, nurses, geriatric specialists, social workers, pharmacists and physical and occupational therapists often work together to deliver care in patients’ homes. Because many of these services have been disrupted by the pandemic, caregivers are encouraged to think creatively about alternatives to in-home care. Virtual platforms, home exercises, consistent nutrition, hydration and family support are particularly valuable tools.

Advertisement

Communication nuances: Lip reading, which is critical for communicating with older patients with impaired hearing, is hindered by face shields and masks. Caregivers must speak clearly and ask for verbal confirmation. Senior patients’ comfort with technology – and the affordability of digital devices – must also be carefully considered.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Patients report improved sense of smell and taste

Clinicians who are accustomed to uncertainty can do well by patients

Unique skin changes can occur after infection or vaccine

Cleveland Clinic analysis suggests that obtaining care for the virus might reveal a previously undiagnosed condition

As the pandemic evolves, rheumatologists must continue to be mindful of most vulnerable patients

Early results suggest positive outcomes from COVID-19 PrEP treatment

Could the virus have caused the condition or triggered previously undiagnosed disease?

Five categories of cutaneous abnormalities are associated with COVID-19