Multidisciplinary perspectives on the importance of early referral and more

Podcast content: This podcast is available to listen to online.

Listen to podcast online (https://www.buzzsprout.com/2243576/17293933)

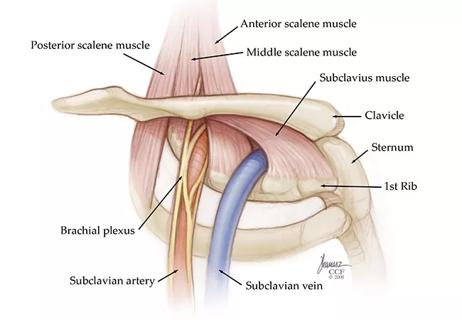

Brachial plexus injuries involve sudden damage to the network of nerves that branch off from the spinal cord at the neck and extend down the upper extremity. They often result from trauma, such as accidents or falls, but some cases are iatrogenic, resulting from inadvertent injury during surgery on the shoulder or other nearby anatomy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“These injuries generally fall into three types,” says Megan Jack, MD, PhD, a peripheral nerve neurosurgeon with Cleveland Clinic’s multidisciplinary brachial plexus injury program. “First are stretch injuries, where the nerve is still in continuity and may ultimately recover on its own. Then there are nerve ruptures, where surgical repair becomes imperative. The most severe form is an avulsion, when the nerve rootlets are pulled from the spinal cord; there are fewer surgical options for avulsions, but function can still be restored in many cases.”

In the latest episode of Cleveland Clinic’s Neuro Pathways podcast, Dr. Jack is joined by plastic surgeon Dennis Kao, MD, a colleague in the brachial plexus injury program, to discuss the essentials of diagnosing and managing brachial plexus injuries. They touch upon the following and more:

Click the podcast player above to listen to the 30-minute episode now, or read on for a brief excerpt. Check out more Neuro Pathways episodes at clevelandclinic.org/neuropodcast or wherever you get your podcasts.

Advertisement

This activity has been approved for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ and ANCC contact hours. After listening to the podcast, you can claim your credit here.

Podcast host Glen Stevens, DO, PhD: Tell us about the timing of intervention for brachial plexus injuries. Is there a point after which surgery shouldn’t be considered?

Megan Jack, MD, PhD: It’s challenging, because it can vary a bit for each patient, but we typically like to do surgery within a year of the injury. The optimal time typically is three to six months afterward. We would not offer surgery for a motor nerve injury after 18 months, as we know that the end plates of the muscle just will not recover, even if there were success in getting a nerve to grow there.

Dennis Kao, MD: It also depends on what function we are trying to restore. There are a few exceptions where we might offer surgery even two or three years after the injury. The one with the greatest chance of success would be for elbow flexion, because even though the patient’s bicep and brachialis will have atrophied, it is technically possible to take a fresh muscle from their leg, transfer it to the arm and make it work if we can find a good donor nerve to drive the muscle. It works best in a case like this when you’re just aiming to restore a single motion for elbow flexion or extension. But when you try to replace intrinsic hand function, which might involve eight or 10 muscles, or the shoulder, which may require four different vectors, it’s very difficult to reconstruct.

Advertisement

Dr. Jack: Yes, and the type of injury is important too. For instance, for spinal cord injury, we can often intervene years later. But for a true brachial plexus injury, intervening within a year is optimal.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Findings could help with management of a common, dose-limiting side effect

Novel therapy “retrains” the brain to disrupt pain signals

Pain specialists can play a role in identifying surgical candidates

Planning continues with critical, patient-focused input from nursing teams

An expert’s take on evolving challenges, treatments and responsibilities through early adulthood

Advances in genomics, spinal fluid analysis, wearable-based patient monitoring and more

An update on the technology from the busiest Gamma Knife center in the Americas

Success for these complex operations requires judicious patient selection and presurgical patient optimization