Patient’s unexplained low blood glucose levels in the absence of diabetes spark quest for answers

A 31-year-old man with a five-month history of episodic weakness and confusion presented to Cleveland Clinic London’s endocrinology outpatient department and was seen by Professor Barbara McGowan, MA, MBBS, MRCP, FRCP, PhD, a consultant in Diabetes and Endocrinology who specialises in treating hormones and metabolic problems.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The patient had first begun noticing symptoms in early 2022. He recalled an incident at a sporting event where he experienced double vision and confusion. At halftime, he could not remember why he was waiting in a queue.

The patient had no history of seizures or related sequelae such as tongue-biting or incontinence. He reported not taking regular medications or using illicit drugs. He had no notable family history. He attributed his symptoms to alcohol consumption, inadequate food intake or excessive exercising. Over time, he noticed the episodes occurring more frequently.

After conducting internet research, he felt his symptoms may have been caused by hypoglycaemia. He began carrying packs of sweets as a precaution.

His symptoms intensified while attending a friend’s wedding in Italy during the summer of 2022. The day before the wedding, he had exercised in the morning, spent all day on the beach and went to bed at midnight. He failed to appear at a luncheon the following day and was unresponsive when friends tried to awaken him in his hotel room at 4 pm. They eventually were able to rouse him by giving him a carbonated soft drink to sip.

After returning to the UK, the patient was referred to Professor McGowan. She saw him in the outpatient clinic following his severe episode in Italy. He had normal weight, body mass index, blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation levels.

“Several conditions can present with symptoms similar to what this patient experienced, including epilepsy, adrenal insufficiency, reactive hypoglycaemia or an insulin-secreting tumour leading to hypoglycaemia,” she says. “So it was important to establish exactly what was happening and why.”

Advertisement

The patient returned to Cleveland Clinic London the next day without eating breakfast so that Professor McGowan and her care team could further assess him.

Initial blood tests showed a low fasting blood glucose level (2.53 mmol/L), with a lower-than-normal HbA1c (28 mmol/mol), normal renal profile and full blood count. A serum morning cortisol level was 287 nmol/L.

“His blood glucose level was extremely low, and more worrying was that he felt OK,” Professor McGowan says. “Most people with a glucose level below 3.0 mmol/L would feel ill. He had clearly been managing this condition for a very long time and his body had developed hypoglycaemia unawareness and adapted to not reacting to such low blood glucose levels.”

After processing the patient’s lab results, Professor McGowan immediately scheduled him for a supervised 72-hour fast.

The patient was admitted to the hospital’s Acute Admissions Unit, which offers rapid assessment and continuous care as well as access to advanced diagnostics and testing for patients in need of acute or urgent medical attention.

Within five hours of admission, the patient began to feel lethargic and exhibited slow speech but remained conscious and coherent. He had no other neurological deficits. His blood glucose was critically low, at 2.11 mmol/L. Blood ketones were negative. His symptoms resolved with oral glucose replacement.

In healthy individuals, if blood glucose levels are low, insulin levels should be low or suppressed. In the patient’s case, Professor McGowan suspected an insulinoma and was expecting to find inappropriately elevated insulin levels to explain the hypoglycaemia. This was not the case, however; insulin levels were appropriately suppressed at <1 mIU/L. A C-peptide level was low at 0.86 mcg/L. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) level was at the lower end of the normal range at 16.6 nmol/L. IGF-2 was 42 nmol/L and an IGF-2: IGF-1 ratio was not raised at 2.5.

Advertisement

These results were indicative of non-islet cell tumour hypoglycaemia (NICTH), driven by IGF-2 or one of its incompletely unprocessed metabolites, also known as big-IGF2. These tumours present with low levels of insulin, a low C-peptide and a low beta-hydroxybutyrate. IGF-1 is typically suppressed whilst the levels of IGF-2 may be normal or elevated. A molar ratio of IGF-2/IGF-1 > 3 (often approaching 10 or more) is diagnostic of NICTH, although the ratio in this patient was not raised, suggesting that the culprit was likely big-IGF2.

The patient was discharged home with a glucose monitor to check BMs regularly and instructions to correct them with glucose/sugary drinks as necessary. The monitor showed frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia over the following weeks.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

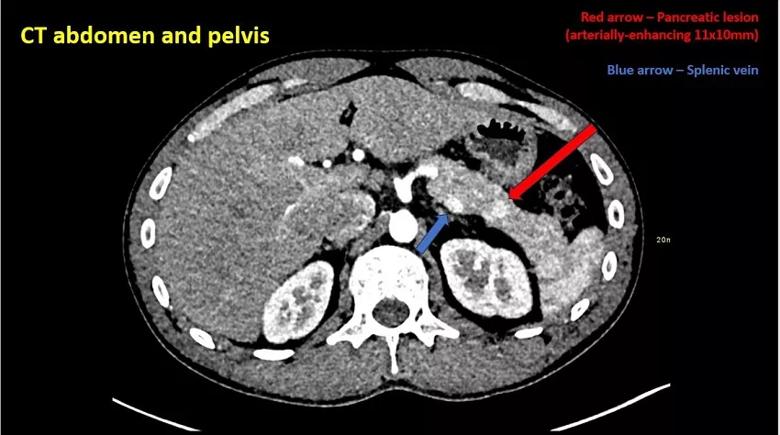

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d0a40762-4357-4d73-8a59-a3c7f21b0472/23-CCC-3907458-CC-London-neuroendocrine-case-report-contrast-CT-850x650-1-jpg)

CT with contrast shows an arterially-enhancing 11 mm x 10 mm lesion in the pancreatic tail.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

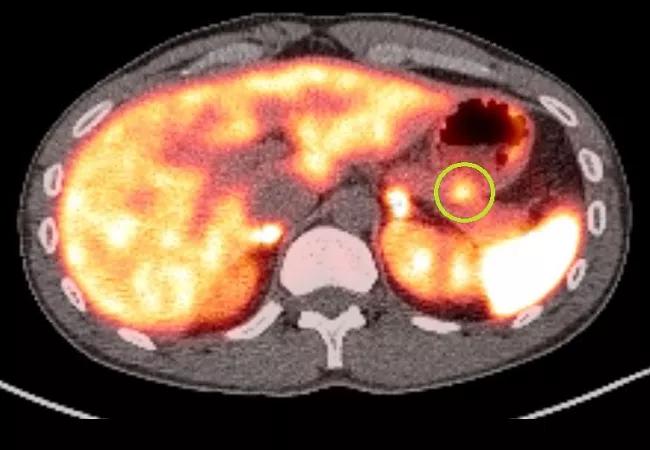

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3d3afdc8-85e6-4915-af74-c8545af8bc0f/23-CCC-3907458-CC-London-neuroendocrine-case-report-PET-scan-850x650-2-jpg)

A gallium-68 dotatate PET scan of the pancreatic lesion shows prominent dotatate uptake (green circle).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ee870fa9-1c72-4552-a951-dc052f398c8c/23-CCC-3907458-CC-London-neuroendocrine-case-report-endoscopic-ultrasound-850x650-1-jpg)

Endoscopic ultrasound performed via a trans-gastric route shows a round hyperechoic T1N0 mass in the tail of the pancreas measuring 11 mm x 11 mm with well-defined margins.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

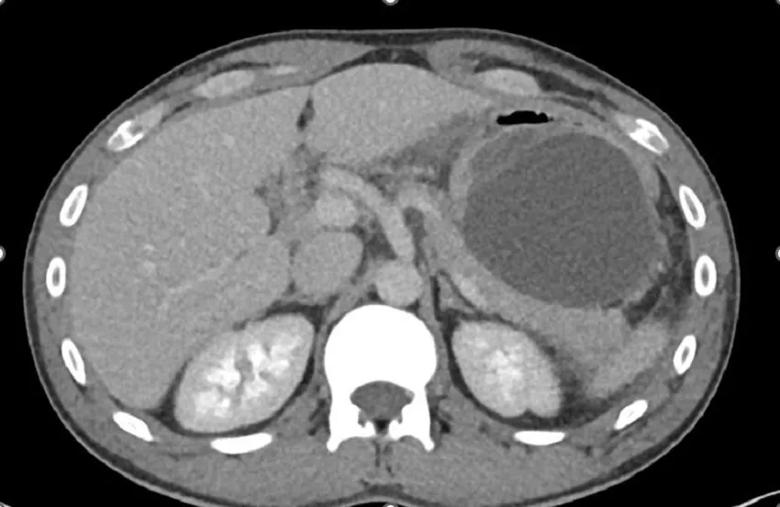

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/10a5419f-b5c6-4c78-b33b-f55d826d7f5f/23-CCC-3907458-CC-London-neuroendocrine-case-report-repeat-CT-850x650-2-jpg)

A repeat CT performed after the patient experienced severe abdominal pain shows left upper quadrant fluid collection adjacent to the pancreatic tail associated with gastric mucosal oedema and acute uncomplicated pancreatitis.

An MRI of the pancreas showed no abnormalities or discernible masses. Due to concerns of an underlying secretory malignancy, Professor McGowan ordered additional imaging.

A CT of the patient’s chest, abdomen and pelvis showed a focal arterially-enhancing 11 mm x 10 mm lesion in the tail of the pancreas, which became iso-enhancing on the portal venous phase. The differential diagnosis was a pancreatic non-islet cell tumour. The diagnosis was further supported by prominent dotatate uptake (SUVmax 9.4) of the same lesion on a gallium-68 dotatate PET scan.

There was no evidence of nodal or distant metastatic disease on the scans. An endoscopic ultrasound and biopsy was performed via a trans-gastric route by Cleveland Clinic London consultant gastroenterologist Dr Gavin Johnson, MBBS, MSc, MD, FRCP, but because the lesion was small, it was not possible to obtain sufficient samples for histological analysis.

Advertisement

One day after the procedure, the patient returned to hospital with severe abdominal pain. His abdomen was firm and tender. Blood tests revealed raised serum amylase (300 IU/L), lipase (1544 U/L) and white cell count (18.19 x 109/L). Blood lactate level was normal (0.9 mmol/L) with no other significant abnormalities. Repeat abdominal CT showed acute uncomplicated pancreatitis with peripancreatic stranding and fluid along the lateral aspect of the body and tail.

The patient was treated conservatively for iatrogenic pancreatitis with intravenous hydration and intravenous patient-controlled morphine analgesia). His pain and nausea persisted for five days. Repeat abdominal CT showed a left upper-quadrant fluid collection adjacent to the pancreatic tail, which was associated with gastric submucosal oedema but no pancreatic necrosis. Four hundred millilitres of clear fluid was drained under radiological guidance and revealed a high amylase level (10,704 IU/L).

The patient continued to experience early morning hypoglycaemic episodes.

Following a multidisciplinary meeting of the histopathology, endocrinology and surgical teams, the consensus was to proceed with a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. With the patient’s consent, Mr Simon Atkinson, BSc (Hons), MBBS, MS, FRCS (Gen), a Cleveland Clinic London consultant pancreaticobiliary and general surgeon, performed a six-hour open procedure to excise the lesion. Histology confirmed a grade 2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour: CD56 positive, synaptophysin positive, chromogranin A positive and Ki-67 3%.

Advertisement

The surgery was successful and there were no complications. During the next few days, the patient spent time in the ICU and then continued recovering on the ward. His blood glucose levels returned to a healthy range.

He was discharged with no issues and received the necessary vaccines and prophylactic antibiotics for protection against encapsulated bacteria. He re-presented to the endocrinology clinic two weeks postoperatively with normal blood glucose levels as confirmed by a normal glucose trace for one month post-operatively and no further symptoms.

After two months, the patient was able to return to work. Seven months later, he reports he is back to full health. He recently participated in a marathon.

“The tumour that the patient had was rare and can often be missed for many years, especially in young people,” Professor McGowan says. “He was extremely lucky. Although his body was compensating, by acting quickly, his friends most certainly helped save his life.”

The surgery should be curative, although follow-up is advised given the rare nature of this tumour.

In summary, this case report describes a rare case of a non-islet cell tumour hypoglycaemia associated with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour. Professor McGowan says it is important to recognize that unexplained hypoglycaemia in the absence of diabetes or post-metabolic surgery can be due to paraneoplastic syndromes. Management includes localisation of these tumours and curative surgical resection if possible.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic endocrinologists work to identify protocols for improving care

Patients spent less time in the hospital and no tumors were missed

While results were negative for metformin, lifestyle counseling showed surprising promise

A review of current evidence and recommendations

Findings indicate clinical decision making should not be driven by initial lesion size

Rare genetic variant protected siblings against seizures and severe hypoglycemia

Maternal-fetal medicine specialists, endocrinologists and educators team up

Cleveland Clinic analysis suggests that obtaining care for the virus might reveal a previously undiagnosed condition