New study counters earlier findings linking drugs with eye disease

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist drugs are gaining popularity as effective glucose-lowering and food-intake-reducing treatment for people with Type 2 diabetes and obesity. However, one randomized controlled trial studying GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide (SUSTAIN-6) indicated the drug was associated with complications of retinopathy, including vitreous hemorrhage and decreased vision in some patients (hazard ratio 1.76). As a result, the labels of semaglutide brands Ozempic® and Wegovy® now include warnings about the risk of vision changes.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

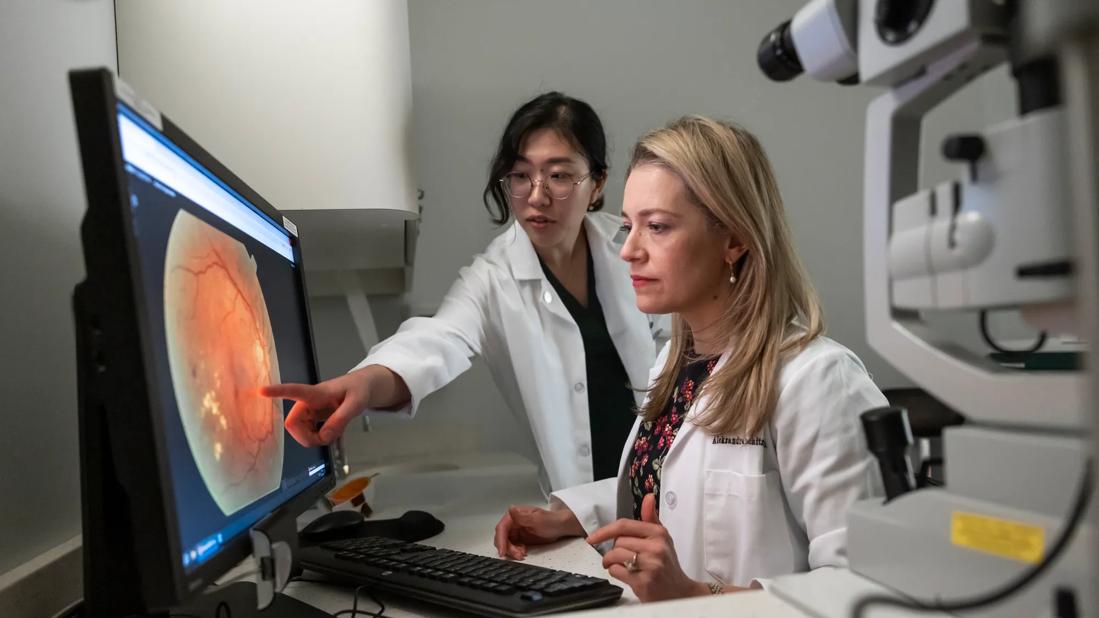

“Patients see the commercials and become concerned when they hear the disclaimer about eye disease,” says Aleksandra Rachitskaya, MD, a vitreoretinal surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. “They ask their ophthalmologist or endocrinologist if it’s safe to take the drug. Endocrinologists turn to ophthalmologists to discuss whether to start certain patients on the drug. There is a lot of uncertainty.”

Adding to the confusion, other studies have not shown a link between GLP-1 receptor agonists and eye disease. Large database studies are inconclusive, notes Dr. Rachitskaya. Some show no relationship between the drug and eye disease; some indicate that the drug improves existing diabetic retinopathy; some indicate that it’s not the drug but rather the rapid improvement in glycemic control that may affect eye disease.

A research team at the Cole Eye Institute recently conducted a retrospective study on the effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists on Cole Eye patients. Their study, published in Ophthalmology Science, found no association between use of the drug and worsening diabetic retinopathy.

The retrospective study evaluated nearly 1,000 patients with Type 2 diabetes who were treated at the Cole Eye Institute between 2012 and 2023. About 700 of them took GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide). A control group of about 300 patients took SGLT-2 inhibitors (e.g., canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin), drugs that are comparable to GLP-1 receptor agonists at lowering blood glucose levels.

Advertisement

The research team compared outcomes of the patients between both groups and with propensity score matching (based on race/ethnicity, age, baseline BMI and glucose level, baseline eye health, and other factors). They found:

“We wanted to cover all the bases on how ‘worsening’ could manifest,” says Julia Joo, a student at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine who was lead author of the study. “That’s why we reviewed both clinical diagnoses and need for procedures.”

Originally, the percentage of patients in the study with ICD-10 codes indicating worsening retinopathy after taking GLP-1 receptor agonists was much higher, notes Dr. Rachitskaya, senior author of the study. But the research team closely reviewed the medical records of each patient diagnosed with worsening eye disease. Most often, the team identified coding discrepancies and not actual worsening disease.

Advertisement

That rigorous review distinguishes the Cole Eye Institute study, Dr. Rachitskaya says.

“In large database studies where retinopathy worsening is based on ICD-10 codes, we don’t have the ability to go back and analyze diagnostic changes in such granular detail,” she says. “So, we need to be aware that methodological issues may be at play. For example, general ophthalmologists or optometrists may diagnose mild retinopathy while, later, a retina specialist may more precisely diagnose the condition as severe. That updated diagnosis may be due to different imaging modalities and more expertise in retinal disease, not disease progression.”

Another distinctive aspect of the Cole Eye Institute study is the study population’s relatively small change in HbA1c level.

“Our patients had good glycemic control at baseline, so their improvement in HbA1c while on treatment wasn’t as dramatic as the population in the SUSTAIN-6 trial,” explains Joo. “That could be another reason why eye disease didn’t appear to worsen as much in our study.”

Historically, patients with diabetes who have used insulin — resulting in dramatic drops in HbA1c — more often have reported worsening diabetic retinopathy, she notes.

This review of GLP-1 receptor agonists in a real-world population contributes to the understanding of the drugs’ effect on patients with diabetes.

“We can’t assume that patients will get worsening eye disease while on these drugs,” says Dr. Rachitskaya. “We should not hesitate to start patients on these medications if they are followed closely by their endocrinologist and ophthalmologist. There may be patient-specific factors that contribute to eye disease, especially in patients who have a dramatic improvement in glycemic control.”

Advertisement

She notes that she is interested to see how the increasing use of these drugs will change the landscape of diabetic retinopathy long-term.

“We know that diabetic retinopathy gets worse the longer you have diabetes and the less control you have over blood glucose levels,” Dr. Rachitskaya says. “Potentially, if patients are started on treatment earlier and have better glycemic control, we might see a general change in manifestations of diabetes in the eye. That remains for future physicians like Julia to report on years from now.”

Joo will graduate from the Lerner College of Medicine in 2025. She plans to apply for ophthalmology residency this fall.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Association revises criteria for the diagnosis and resolution of severe conditions

What to consider in the management of euglycemic DKA

Less than 50% of patients with diabetes get appropriate ophthalmic screening through primary care referrals

Familiarity will enhance its accessibility for patients with diabetes

Study highlights the value of quantitative ultra-widefield angiography

Longevity in healthcare, personal experiences may provide caregivers with false sense of confidence

Maternal-fetal medicine specialists, endocrinologists and educators team up

Spinal cord stimulation can help those who are optimized for success