Editor’s note: This article originally appeared here in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine and has been republished with permission.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

By Glenn T. Werneburg, MD, PhD and Daniel D. Rhoads, MD

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common human infections. But the urine culture, the cornerstone for laboratory diagnosis of UTI, is imperfect. It has a high frequency of false-positive and false-negative results, and its diagnostic threshold is debated. Also, urine culture takes 2 to 3 days to result, and antibiotics are often initiated empirically while awaiting final culture readings. Further, asymptomatic bacteriuria—the presence of bacteria in urine in the absence of UTI symptoms— generally does not warrant treatment.

Current guidance based on an expert panel consensus by Claeys et al1 recommends appropriate laboratory urine testing and interpretation of the results when the potential for UTI is being assessed. The guidance describes approaches to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use and the misdiagnosis of UTI and is organized according to the procedure for urine culture: ordering, processing, and reporting.

The authors of the guidance, an expert panel representing multiple areas of expertise, used a modified Delphi approach to determine best practices in diagnostic stewardship relating to urine culture. The central tenets of the guidance are avoiding testing and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria, and avoiding fluoroquinolones as first-line treatment for acute cystitis, principles corroborated by other major guidelines.2–4

Here, we outline the current guidance and discuss its impact on daily practice. Finally, we discuss specific patient groups and scenarios to which the guidance will not apply.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c0a7b91d-346e-4464-b4c3-08c75b7f3015/23-URL-3524809-Inset1_jpg)

The guidance1 relates to urine culture diagnostic stewardship in both outpatient and inpatient settings and specifically addresses the emergency department, inpatient, ambulatory, and long-term care practice settings.

This review is intended for clinicians who diagnose and treat UTI, and for those who perform or report urine studies. These include general practitioners, emergency medicine physicians, infectious disease physicians, geriatricians, and laboratory medicine medical directors. This review is also intended for urologists, for whom the discussion of exceptions to the guidance in urological patient cohorts is particularly relevant.

The guidance includes 18 general statements written by an expert panel chosen from geographically disparate practice settings. The panel included 15 individuals with specialization in healthcare epidemiology and quality improvement, medical informatics and decision support, infectious diseases, clinical microbiology, antimicrobial stewardship, and urology, and with expertise in UTI management, diagnostic stewardship, clinical microbiology, and infection prevention. Thirteen of the 15 panelists were physicians, and 10 of those were infectious disease physicians. No clinical pathologists trained and board-certified in the general practice of laboratory medicine were on the panel. The guidance panel reviewed relevant literature on diagnostic stewardship from electronic databases to generate a final list of clinical questions to guide the development of survey questions for use in the modified Delphi process. A modified Delphi approach using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method5 was used to determine best practices in diagnostic stewardship relating to urine culture. Guidance panel experts ranked their recommendations on a Likert scale, and subsequently met to further discuss points of disagreement. A second round of review was performed, and the final body of guidance statements was generated.

Advertisement

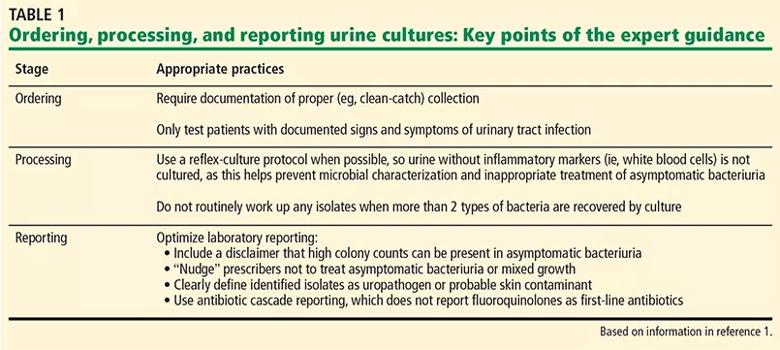

Key points of the guidance are summarized in Table 1.1 The main recommendations focus on optimizing urine culture diagnostic stewardship and antibiotic stewardship. The recommendations are broadly classified by ordering, processing, and reporting of urine cultures, along with associated appropriate and inappropriate practices.

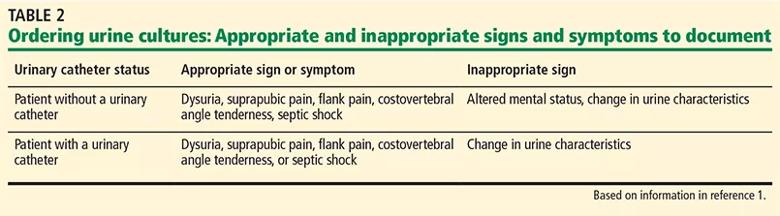

Appropriate practice for ordering a urine culture includes documentation of signs or symptoms (Table 2)1 of UTI in order to obtain a urine culture, to replace stand-alone urine culture orders with a “reflex-culture” protocol (i.e., when urinalysis and urine culture are ordered together, the culture is performed only if urinalysis criteria are met) based on urinalysis results, and to automatically cancel repeat urine cultures within 5 days of a positive culture, if during the same hospital admission.

Inappropriate practice is the inclusion of culture in standard order sets (emergency department, hospital admission, preoperative, altered mental status, and falls assessment), or ordering urine cultures in response to a change of urine characteristics.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8f6ba2c7-b1d1-4c63-9498-e38066aeb711/23-URL-3524809-Inset2_jpg)

Appropriate practice includes using an elevated white blood cell count on urine microscopy as a criterion for reflex culture when a urine culture is ordered by a clinician. Further, the collection method (eg, midstream clean catch, indwelling catheter, in-and out straight catheterization) should be documented before processing cultures.

Inappropriate practice includes automatically obtaining reflex cultures based on urinalysis results in cases where a urine culture was not specifically requested.

Advertisement

Appropriate practice should include urine culture reports informing clinicians that counts greater than 100,000 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL may not represent true infection in the absence of symptoms, and reminding clinicians not to treat asymptomatic bacteriuria or mixed flora. Further, the culture report should differentiate between typical uropathogens and contaminants. Identification and susceptibility testing of isolates should not be routinely reported when more than 2 unique bacterial isolates are present in culture.

For example, our clinical laboratory provides the following comments along with results of cultures with growth of 3 or more organisms: Mixed microbiota. No further workup. Mixed microbiota can be due to urine contamination with skin bacteria at time of collection or presence of a long-term urinary catheter. If a new culture is needed, please consider re-education of the patient on proper midstream collection technique or straight catheterization for urine collection.

An additional appropriate practice, termed cascade reporting, is that antibiotics recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) should be preferentially reported if an organism is susceptible, and fluoroquinolone susceptibilities should be withheld unless there is resistance to preferred oral antibiotics.

Inappropriate practice would include suggesting not to treat if less than 100,000 CFU/mL of bacteria is recovered in culture, and withholding culture information and waiting for the prescriber to contact the clinical microbiology lab to release the results.

Advertisement

The goal of the current guidance is different from the IDSA/American Society for Microbiology (ASM) guidelines6 in that the focus is the best implementation of urine testing for the optimal treatment for UTI. It seeks to provide system-based guidance to influence diagnostic stewardship on a large scale.

The 2018 IDSA/ASM “Guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases,”6 which includes urine culture guidance, does not disagree with any of the guidance offered by Claeys et al,1 but it does offer additional points. The IDSA/ASM guide states that urine should be placed in boric acid (“gray-top”) preservative tubes if transported at room temperature. Alternatively, urine can be refrigerated after collection and during transport, or urine can be inoculated within 30 minutes of collection if not refrigerated and not preserved with boric acid. The IDSA/ASM guide also states that a reflex-culture protocol based on pyuria should be a locally approved policy.

The guidance by Claeys et al does not address preanalytical considerations to prevent bacterial overgrowth during transport. Preanalytical practice effectiveness is systematically reviewed elsewhere.7 Additionally, it is beyond the scope of the guidance to inform as to how to create and implement a reflex-culture approach at a local level.

The clinical impact of the guidance can be stratified into 2 main categories: reduction in unnecessary antibiotic use, which is good antimicrobial stewardship practice, and cost avoidance through decreased urine culture testing and inappropriate therapy, which is good diagnostic stewardship practice.

Reduction in antibiotic overuse

Antibiotic exposure is a known strong risk factor for antibiotic-resistant UTI and other infections.8,9 Antibiotic use is associated with increased resistance at the population level.10 Antibiotic exposure is also associated with increased risk for Clostridioides difficile colitis and vulvovaginal candidiasis due to disruption of the healthy microbiome.11,12 Thus, reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics is a critical aspect of delaying and minimizing the emergence of resistance and reducing collateral pathology. The guidance by Claeys et al provides actionable measures to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use during each stage of the urine culture process, ie, ordering, processing, and reporting.

Recommended measures are provided to avoid unnecessary detection and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. In one study, about 70% of patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria were treated with antibiotics,13 despite the lack of benefit and the discordance with existing guidelines.2–4,14 The current recommendation is that the clinician be prompted to document signs and symptoms of infection when requesting a urine culture. The assignment of a symptom complex to a culture is designed to reduce testing in the absence of UTI symptoms and, thus, to subsequently reduce unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Further guidance designed to limit treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria includes the recommendation that culture reports remind, or “nudge,” clinicians to not treat asymptomatic bacteriuria, and that even high colony counts (> 100,000 CFU/mL) may not represent true infection in the absence of signs and symptoms.

Further, the guidance provides a strategy to decrease the time and resources required to achieve a final laboratory result by screening with urinalysis before culture. A urine culture generally takes 2 or more days to return a result with antibiotic susceptibility test interpretations. However, if a reflex-culture protocol is employed as the guidance recommends, the time to final result would often be significantly reduced, and culture would be obviated. This practice could lead to a reduction in unnecessary antibiotic use.

In 2019, there were more than 36 million hospitalizations in the United States.15 It is estimated that about 27% of hospitalizations are associated with a urine culture.16 At about $10 per culture (based on the Medicare clinical laboratory fee schedule CPT code 87086),17 this translates to almost $100 million annually in the inpatient setting alone. These data, coupled with the large quantity of urine cultures obtained in the emergency, ambulatory, and long-term care settings, underscore the opportunity for cost avoidance associated with a reflex-culture protocol. Further cost savings would be associated with the reduction in treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria.

The main tenet of nontreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria described in the guidance by Claeys et al1 is agreed upon by other major societies. IDSA, the American Urological Association (AUA), and the European Association of Urology (EAU) agree that asymptomatic bacteriuria should generally not be treated outside the context of pregnancy or prior to a subset of urologic interventions.2,4,18 The guidance is also corroborated by the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely health-education campaign, which recommends not obtaining urine cultures in the absence of symptoms and not treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.19,20 The IDSA/ASM guide to laboratory testing recommends that a reflex-culture policy be established locally.6

Existing guidelines vary as to the cutoff for uropathogen growth on standard culture. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention requires at least 100,000 CFU/mL on urine culture to meet its criteria for diagnosis of UTI.21 Conversely, the IDSA/ASM guidelines have a more flexible threshold and include growth less than 100,000 CFU/mL.6

Similar to the guidance by Claeys et al,1 the guidelines from the IDSA, AUA, and EAU emphasize that fluoroquinolones should be avoided in uncomplicated cystitis. For example, the IDSA/European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases guidelines3 note that fluoroquinolones are highly efficacious but have the propensity for significant off-target effects and should be reserved for uses other than acute cystitis, and should be considered an alternative rather than a first-line regimen. The EAU guidelines state that fluoroquinolones should not be used to treat uncomplicated cystitis,4 and the AUA guidelines2 note that the serious adverse effects associated with fluoroquinolones including tendonitis, tendon rupture, QT interval prolongation, and C difficile infection generally outweigh the benefits in uncomplicated UTI. Of note, the IDSA, AUA, and EAU recommendations do not necessarily apply to patients with complicated UTI (eg, aberrant anatomy, foreign body) or compromised immunity.

Most of the statements in the Claeys et al guidance are generally accepted good practice. However, the guidance also adds weight to the increasingly common practice of using a reflex-culture approach to prevent the culture of urine specimens in which no inflammation is present (ie, no white blood cells).

The guidance deemphasizes the traditional cutoff of 100,000 CFU/mL as a diagnostic criterion for UTI, which is consistent with IDSA’s previous deemphasis of this cutoff.6 The cutoff of 100,000 CFU/mL was developed based on a population with pyelonephritis and has since proven to be inadequate.22–27 The current guidance reemphasizes generally accepted principles, ie, that even cultures with uropathogen growth of greater than 100,000 CFU/mL do not require treatment in patients without symptoms, and that true UTI may be associated with uropathogen growth of less than 100,000 CFU/mL.1

The framework provided for the stewardship of fluoroquinolone use may reduce prescription of this drug class. In 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration added a boxed warning to fluoroquinolones due to their association with tendonitis and tendon rupture.28 However, there is evidence that the boxed warning has had little effect on prescription patterns of fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated UTI,29,30 and little effect on the high rates of fluoroquinolone resistance.31 We believe that one of the greatest impacts of the current guidance could be in reversing these trends in daily practice by encouraging laboratories to avoid reporting fluoroquinolones as routine, first-line antibiotics for UTI.

The guidance by Claeys et al does not apply to a number of clinical scenarios. Children, pregnant patients, renal transplant recipients, and severely immunocompromised patients were specifically excluded. However, screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is indicated in pregnancy,18 and the benefits of treatment may outweigh the risks.32

Screening for and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria is indicated prior to urologic surgical procedures that involve manipulation of the upper urinary tract or that cause mucosal trauma,18 and the benefits of treatment may outweigh the risks.33

For patients who have a urinary catheter or who require intermittent catheterization, and for patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction or bowel interposition in the urinary tract (eg, ileal conduit, neobladder), the utility of a reflex-culture approach has not been empirically established. Further, the IDSA guidance for catheter-associated UTI states that pyuria should not be used to differentiate between catheter-associated UTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria.34 UTI symptoms in these patients may be subtle and variable and can include increased spasticity, autonomic dysreflexia, and a sense of unease.34–36 Symptoms must be considered in the context of the physical examination and urine studies, especially given that the urine of these patients is generally chronically colonized with bacteria.

Urine cultures with complete antimicrobial susceptibility profiles may be required in urologic patients regardless of urinalysis results. Such circumstances may include contexts prior to or following urologic procedures, as well as cases of suspected prostatitis, epididymoorchitis, fistulae, or recurrent UTI.

The clinical appropriateness of performing cultures for urology patients should be at the discretion of the supervising urologist or urology practitioner, and stand-alone cultures should not be reverted to reflex culture in urologic patients without prior discussion with the urology team. Similarly, a culture within 5 days of another culture should not be cancelled in a urologic patient before a discussion with the team requesting the culture. Such a culture may be necessary in the context of refractory symptoms, to assess the possibility of recurrent infection or continued contamination. In urologic patients, species-level identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of all isolates grown in urine may be necessary before endourologic procedures, even in cases of more than 2 organisms, as polymicrobial interactions can play a role in urologic infection,37 and so this should be left to the discretion of the urology team.

In select cases of UTI, fluoroquinolone use is appropriate. For example, the EAU guidance states that fluoroquinolones are an effective oral regimen for uncomplicated pyelonephritis.4 Further, fluoroquinolones often exhibit excellent penetration of the prostate and thus are associated with significant benefit, particularly if there is suspicion for prostatitis, or in patients with febrile or recurrent UTI with prostatic involvement.4,38 Thus, fluoroquinolone susceptibilities must be reported in such cases.

In daily practice, a balance must be achieved between diagnostic stewardship and clinical practicality. For example, the guidance places additional ordering demands on the clinician, and there should be a method in place to rapidly designate an exception to the laboratory that processes the specimens. A series of “hard stops” for the clinician when placing orders may lead to inappropriate care when such hard stops are not applicable, as in the exceptional circumstances discussed above.

In early urosepsis, a subset of patients may not be able to describe symptoms, but changes in behavior or mental status may be witnessed or reported. Even in the absence of a catheter, the completion of a urine culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing should be based on clinical discretion.

In some patients with catheters, UTI may present with fever without septic shock,34 particularly in those unable to communicate, and thus urine culture should be processed at the discretion of the requesting clinician.

Recently, machine learning has been shown to improve antimicrobial stewardship. Specifically, the use of machine learning-generated antibiotic recommendations was associated with minimization of antimicrobial resistance.39 As these models mature and undergo further validation, their integration within antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship is poised to lead to further reduction in antibiotic overuse, antimicrobial resistance, and financial burden to patients and the healthcare systems.

Disclosures

Dr. Rhoads reports work as advisor or review panel participant with BD Diagnostics, Luminex, Roche Diagnostics, Talis Biomedical, and Thermo Fisher Scientific; teaching and speaking with Cepheid; and research (principal investigator) with bioMerieux, Cepheid, Cleveland Diagnostics, Hologic, Luminex, Q-Linea, Qiagen, Specific Diagnostics, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Vela Diagnostics. Dr. Werneburg reports no relevant financial relationships which, in the context of his contributions, could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Advertisement

How this technology is improving antibiotic use and stewardship

Up to 3 days faster than waiting for urine culture results

Pediatric urologists lead quality improvement initiative, author systemwide guideline

Fixed-dose single-pill combinations and future therapies

Reproductive urologists publish a contemporary review to guide practice

Two recent cases show favorable pain and cosmesis outcomes

Meta-analysis assesses outcomes in adolescent age vs. mid-adulthood