Despite challenges, mother and baby are thriving

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/34758582-44ba-4665-83c0-009f36f87e30/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Hero_jpg)

20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Hero

In a complex fetal surgery procedure performed at Cleveland Clinic, a multidisciplinary team led by pediatric and fetal surgeon Darrell Cass, MD, exteriorized a large, right-sided lung mass in a partially delivered fetus, enabling a safe birth and subsequent removal of the tumor.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In the three-hour operation, known as EXIT (ex-utero intrapartum treatment)-to-resection, the fetus remains on utero-placental “bypass” while the mass is exposed and resected. Full delivery and ventilation generally follow. In this case, the placenta worked poorly, requiring an emergency thoracotomy, delivery and resuscitation; contingencies that the team was prepared to undertake.

Fetal MRI at an outside institution revealed a large, right-sided lung mass. The fetus had severe fetal hydrops, with anasarca and significant ascites. Prior to referral, the mother received two courses of betamethasone.

“The mother presented at 33 weeks’ of gestation for a second opinion,” states Dr. Cass. “We performed a repeat fetal MRI, which revealed improving hydrops, but massive polyhdyraminos, and a large right-sided lung mass that was pushing the heart and esophagus to the left side. The CCAM volume ratio of the lesion, a measure of mass size relative to the fetus, remained 2-2.1, which was quite high at this late stage in pregnancy.“

“The family had been counseled that there was not much that could be done and the prognosis was poor. At the time of our evaluation, the fetus’s heart function looked good. We felt there were essentially three options. The first option would be to allow delivery to occur naturally, intubating the baby and supporting it as best we could. With this strategy, we worried there would be immediate respiratory failure requiring high ventilator pressures with the mass inside of the closed chest cavity and cardiac compression from the mass, that likely would expand with air trapping of small cystic spaces. There is often a vicious cycle with escalation of ventilator pressures, increased cardiac compression and worsening physiology. An urgent operation would be needed in a difficult situation that would have a high risk for poor outcome. Another option would be EXIT-to-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), in which we put the fetus on bypass prior to delivery to preserve gas exchange in the setting of respiratory failure; however, ECMO comes with significant risk, including bleeding, stroke and brain damage, and I was not convinced ECMO was going to be needed for this infant. A third option, which hadn’t been presented to the family, was EXIT-to-resection, in which we create a stable operative environment to expose and resect the lung mass prior to birth. We use the EXIT-to-resection strategy to deliver fetuses with persistently large fetal lung masses late in gestation with evidence of mediastinal compression or hydrops. In this case, the fetus had both indications, and we felt like the patient was a good candidate for this EXIT-to-resection approach,” Dr. Cass says.

Advertisement

Dr. Cass has unique experience with the EXIT-to-resection procedure, having performed it 18 times previously during his career. In addition, he has performed open fetal surgery for lung masses (in which the fetus remains inside the uterus postoperatively) another five times. He coined the term “EXIT-to-resection,” helped refine the operation, and published a paper with a large series of patients that have helped determine its use. He joined Cleveland Clinic in 2017 to develop and lead a fetal surgery program. Although Cleveland Clinic’s fetal surgery team has completed an EXIT-to-airway procedure before, this was its first EXIT-to-resection.

“The EXIT-to-resection procedure is totally unique,” says Dr. Cass. “There are not many surgeons who have this level of experience, which certainly helps when complications arise.”

During the EXIT-to-resection procedure, maternal and fetal anesthesiologists use deep general anesthesia of the mother to maintain uterine relaxation and optimize placental perfusion and function. The mother and fetus are monitored closely using an arterial catheter in the mother, and ongoing ultrasonography and echocardiography for the fetus. Ultrasound is also used to identify the fetus’s position and the location of the placenta to guide the uterine incision.

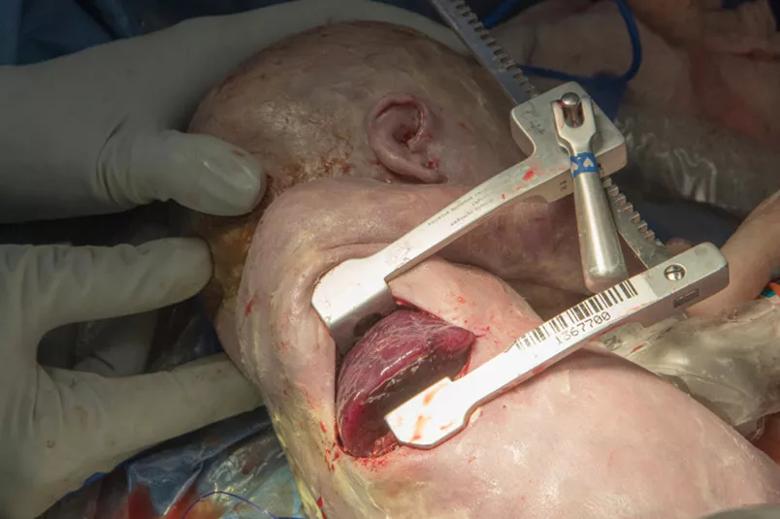

The fetus’s head, upper extremities and torso are exposed, the latter to accommodate pulse oximetry. The fetus is intubated, though ventilation is avoided to preserve the fetal and placental circulation and prevent the lesion from expanding (from air trapping within the malformation’s cystic spaces). At this point, an IV is placed, followed by fetal thoracotomy. The chest is opened to exteriorize the mass, which is often resected prior to delivery. In some instances, the fetus might be delivered with the mass exteriorized through an open chest, ventilated, and the lobectomy completed following delivery. That is what happened in this case.

Advertisement

The procedure took place at 36 weeks and two days of gestation.

“It was a little difficult because the mother is 4’11”, her uterus was massively overdistended due to the polyhydraminos (amniotic fluid index of 56), the placenta was anterior and the baby was transverse. Optimally, we try to make our hysterotomy in the lower uterine segment to minimize long-term complications. There were a number of variables in this case, including the polyhydramnios and anterior placenta, but we were able to use a lower uterine incision successfully. The placenta was right there, but there was no bleeding and mother and fetus seemed to be doing well,” Dr. Cass recalls.

“Following hysterotomy, the head, torso and right arm were exposed, and an IV placed,” Dr. Cass continues. “Francine Erenberg, MD, our pediatric cardiologist, alerted us that the fetus was developing bradycardia. There was no sign of bleeding or placental separation, but the placenta perfusion seemed compromised in some way. Efforts to reposition the fetus and umbilical cord were unsuccessful.”

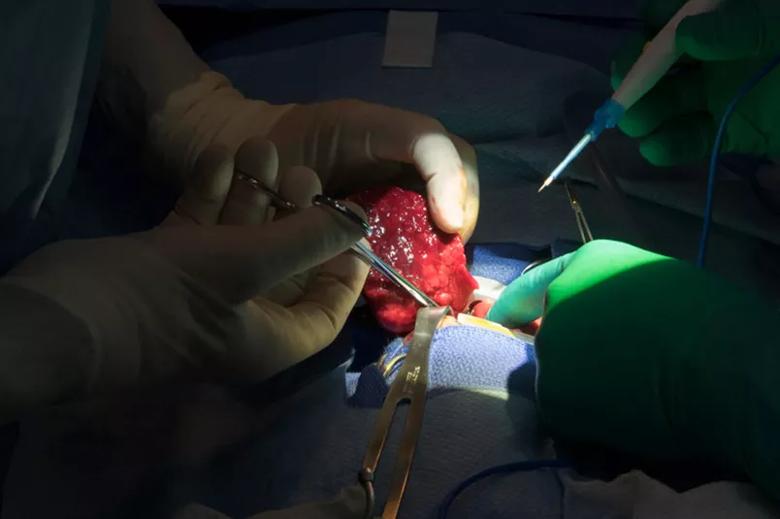

“I opened the right side of the fetus’s chest quickly, placed a retractor, and brought the lung mass out of the chest to help decompress it. The mass was huge. Then, since the umbilical cord had already shut down, we cut it, delivered the baby quickly, and moved to another table we’d set up in the operating room in case of an emergency.”

“The baby was intubated and resuscitated. I performed a right lower lobectomy, removing the mass. The mass itself was much bigger than we expected. It measured about 6 cm on fetal MRI prior to surgery. By the time we removed it, the mass was 7 cm, which is really big in a 2.5 kg baby.”

Advertisement

“Once we closed the chest, the baby began to stabilize. The patient was moved to the NICU, and has recovered steadily since. We expect to discharge to home in about one weeks’ time. The mother has recovered smoothly as well.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/82853059-7d9f-429a-8fe9-c637ffed7b26/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-1-jpg)

The fetus’s head and upper extremities are exposed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7b456a09-6c8c-4de9-a5be-e8b30ce4d352/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-3-150x113-jpg)

The chest is opened.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/449d32ec-7faf-4f89-8c33-a8217b86e51f/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-4-jpg)

The chest wall retractor allows exteriorization of the mass.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3450b390-5d6d-45e6-a7c3-682dab6545f8/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-5-jpg)

Ultrasound is used to examine the impact of the mass on the chest cavity.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5942bd70-ad89-4427-ba0a-d48b7a455c33/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-6-jpg)

The baby is delivered and ventilated.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/766b2bad-3ddb-4a38-a6b6-d2abc74d40ea/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-11-jpg)

The 7 cm mass is removed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/fddc76cd-8b20-4491-bb0c-7f451d69b808/20-DDI-1908231-CQD-Cass-EXIT-Surgery-Lung-Mass-Slide-13-jpg)

The baby recovers in the NICU.

Dr. Cass has high praise for his colleagues on Cleveland Clinic’s multidisciplinary fetal surgery team, whose diligent preparations had life-saving implications. The fetal surgery team — composed of more than a dozen physicians and nurses specializing in pediatric surgery, maternal-fetal medicine, pediatric cardiology, pediatric and obstetric anesthesiology, and neonatal intensive care — met prior to surgery to discuss the case and each operative step, to review their roles and how they would manage potential complications.

“We always do a walk-through to rehearse different steps. In this case, our preparation may have saved the baby’s life,” Dr. Cass says. “We always have a second operating room on standby in case the fetus needs it. This was the first time I set up a second operative table in the same room, which reduced the risks involved in moving the baby, allowed for faster intervention, took advantage of economies of scale and facilitated teamwork.”

“Teamwork is vital to the success of fetal surgery. There are many variables at play as we care for the mother and the fetus as it transitions from the in utero environment to life as a neonate. We have to be prepared with multiple contingencies depending on the minute-to-minute status of the mother and fetus. In this case the placenta did not function as effectively as typical. Dr. Erenberg did a great job monitoring the baby, and alerted us immediately to the first signs of fetal distress. We also had maternal fetal-medicine specialists Amanda Kalan, MD, and Uma Perni, MD, multiple anesthesiologists (including Tara Hata, MD, and Yael Dahan, MD) present to ensure the safety and comfort of both mother and baby,” Dr. Cass concludes.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years