Technically demanding procedure reduces morbidity and recovery time for donors

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9aec3927-b2aa-4471-a078-805b2437af28/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-hero-650x450_jpg)

19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-hero-650×450

A Cleveland Clinic surgical team led by Choon Hyuck David Kwon, MD, PhD, has successfully performed the Midwest’s first purely laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy for liver transplant (LDLT).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The procedure is technically demanding and is available at only a few hospitals worldwide, mostly in Asia. The laparoscopic approach significantly reduces the invasiveness and morbidity of living donor liver procurement, improving safety for patients, shortening recovery times and potentially motivating more people to donate.

The laparoscopic hepatectomy and transplant were performed in August. The donor, a 29-year-old Florida man, was discharged after five days and was off all pain medication one week postoperatively. He has recovered without complications.

The 66-year-old male recipient, also from Florida, who suffered from liver failure due to cryptogenic cirrhosis, received 33% of the donor’s liver. He has recovered well and now has normal liver function.

“The operation went perfectly. I couldn’t have been happier about the performance of our surgical team,” says Dr. Kwon, the Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute’s Director of Laparoscopic Liver Surgery.

Dr. Kwon is one of the world’s most experienced laparoscopic living donor liver surgeons, having performed more than 75 of the procedures at South Korea’s Samsung Medical Center since founding that institution’s program in 2013. He joined Cleveland Clinic in November 2018 and spent nine months preparing to launch laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy services here.

Cleveland Clinic is only the second U.S. medical center to offer the minimally invasive, purely laparoscopic approach for LDLT. Since the initial procedure in August, Dr. Kwon has performed an additional four surgeries.

Advertisement

“Our goal is to increase the availability of laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy so that more donors can recover from the operation faster and easier. We also want to become a leading center of expertise in this procedure,” Dr. Kwon says.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0e7e1f29-1f02-4523-aede-723b71197205/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-1-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5f068f2c-fe64-46f2-8bec-0eaa80892556/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-2-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e75520f5-36fd-4141-a242-e14795b05cb7/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-3-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e0584827-98fa-426e-b2d8-8798ad896724/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-4-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/afb5218f-cd3c-47be-b9f2-28c6ee00b31e/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-5-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a81c7824-49e2-4ba7-bb8a-60ca52f2a6e5/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-6-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/56934404-13ff-4ed7-aaa7-1754004f32d7/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-7-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0c74c3b1-2d21-4379-b23b-d4fc631c6bbb/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-8-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/daefd8c6-908d-4570-9f7c-57661ae0e3ea/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-10-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/61fa7730-1113-49ba-95be-387c459e9fcf/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-11-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5fd4c4e2-a97e-4d9f-8ab1-6e9de620c68a/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-12-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e61f7494-ec0f-4ecc-83e8-a65f3197ec9c/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-13-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/dd2d0799-e31b-4a86-ae57-c4596b5a4a1e/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-14-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b0bd5280-16f1-418e-b842-bb5fb9e3f242/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-15-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1a34a567-458c-4e92-8a71-93f784d72c36/19-DDI-3939-LAP-LDLT-16-650x450-150x104_jpg)

Slide 1/15

LDLT debuted in 1988 in response to the extreme shortage of deceased-donor organs and long wait times and high mortalities prior to transplant. It was performed as an open technique, owing to the complexity of graft mobilization and resection. The procedure was an extension of the experience surgeons had gained in reduced-size and split-graft deceased-donor transplants.

Initial LDLTs were adult-to-child, with expansion in the early 1990s to adult-to-adult cases. Left-lobe living-donor hepatectomies were less challenging, technically, but because the left lobe was often undersized for an adult recipient, surgeons developed a right-lobe LDLT technique that became the preferred methodology in many Asian countries, where LDLT predominates.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b8c79e1c-95c5-43f8-aaea-93fe6ada504d/19-DDI-3939-laproscopicIncisionsLiver-inset-770x979_jpg)

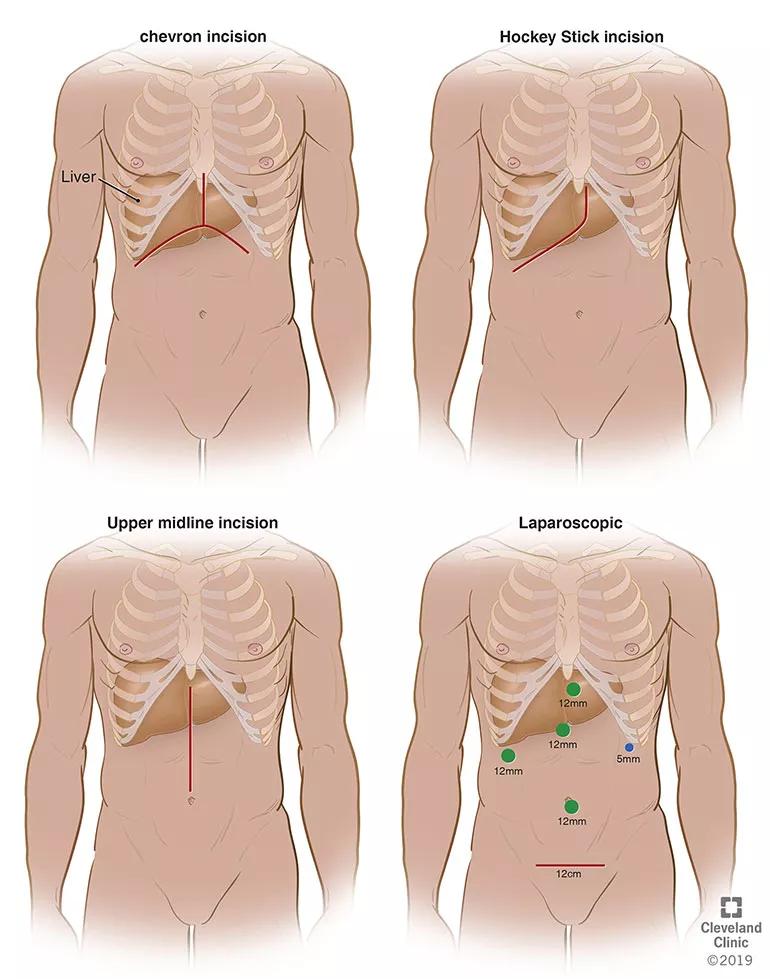

From upper left to lower right, this illustration shows the decreasing size of incisions that surgeons have used over time as the living donor hepatectomy procedure has become less invasive.

With the safety of altruistic donors paramount, and in consideration of the significant morbidity and cosmetic concerns inherent with open, large-incision liver donor surgery, some surgeons began to contemplate whether the minimally-invasive laparoscopic techniques employed in liver cancer resection and renal transplantation could be adapted for living-donor hepatectomy.

Advertisement

In 2002, a group of French surgeons was the first to show the feasibility of a laparoscopic approach for living liver donors, performing two successful parent-to-child transplants involving left lateral sectionectomy.

Laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy subsequently demonstrated advantages in reduced blood loss, postoperative morbidity, length of recovery and scarring compared with traditional open surgery. But the technique has not been widely adopted due to concerns about donor safety and a steep learning curve that requires expertise in both laparoscopic liver resection and LDLT.

“LDLT is one of the most complex surgeries that can be done laparoscopically,” Dr. Kwon says. “You need a lot of preparation. When I started the laparoscopic living liver donor program at Samsung Medical Center, our team had already performed more than 1,000 LDLTs and more than 350 laparoscopic liver resections, including more than 100 major hepatectomies. That’s how I gained confidence that I could manage the laparoscopic living-donor hepatectomy.”

That overlapping experience is essential, says Charles Miller, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s Enterprise Director of Transplantation and Director of the Transplant Center.

“One of the reasons laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy for LDLT has proliferated in many Asian countries is that liver surgery and laparoscopic surgery are taught in the same program,” Dr. Miller says. “Here, liver surgery is taught in hepatobiliary programs and laparoscopic surgery is taught in minimally invasive surgery fellowships. Very few people become expert liver surgeons and expert minimally invasive surgeons in the United States. Dr. Kwon is both. He uses all the tools.”

Advertisement

Preparing for the first procedure at Cleveland Clinic involved bolstering and fine-tuning the institution’s existing LDLT and laparoscopic liver surgery capabilities, as well as rehearsing all aspects of the donor operation.

“You need to practice daily,” Dr. Kwon says. “The whole team needs to be used to the setting,” including surgical instrument placement and smooth teamwork during complex laparoscopic liver procedures. “About two months ago, I felt we were ready and we began recruiting patients.”

Careful donor selection in laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy is essential for optimal outcomes. Cleveland Clinic’s donor criteria include low body mass index, preferably less than 30; expected future liver remnant volume greater than 30%; and normal biliary and vascular anatomy. Surgical planning is aided by creation of a three-dimensional model of the donor’s liver, derived from a computed tomography scan.

In Cleveland Clinic’s initial case, the surgical team determined that the donor’s left liver lobe would the best graft to use. Fortunately, the lobe showed favorable anatomy for a laparoscopic approach. With the aid of the 3-D model, Dr. Kwon was able to visualize the precise biliary and vascular anatomy preoperatively and make detailed, step-by-step surgical plans in order to have the best outcome.

The recipient had been diagnosed with cryptogenic cirrhosis. Although his physical condition and quality of life had markedly deteriorated — he was experiencing hepatic encephalopathy immediately prior to admission — his Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, which is used to determine priority for organ allocation, did not reflect an imminent need, making it difficult to obtain a deceased-donor graft.

Advertisement

“Cryptogenic cirrhosis is one of the diseases where the patient can be quite sick but doesn’t have a high MELD score,” Dr. Kwon says. “They may have to wait many years until their liver function has deteriorated to the point where they have the option of a deceased-donor transplant. Many of those patients experience complication from cirrhosis that are not reflected in their MELD score, and many die while on the waiting list. So they’re stuck in a situation where they either cope with a greatly reduced quality of life and face possible death while waiting for an organ, or opt for a living donor transplant.”

Fortunately for this patient, his daughter’s boyfriend was a willing donor and a blood type match. “Every person who steps forward to donate to save someone is very courageous,” Dr. Kwon says. “I always look up to their heroic gestures.”

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://www.youtube.com/embed/MtUojwi99-k?feature=oembed)

First Purely Laparoscopic Living Donor Hepatectomy for Liver Transplant at Cleveland Clinic

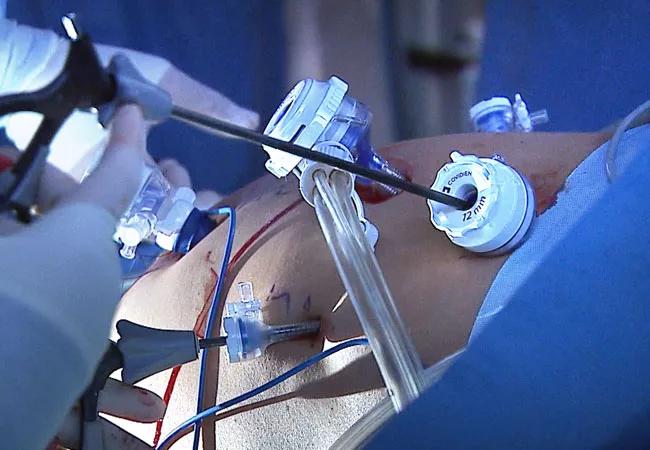

For the operation to retrieve the donor graft, the patient was placed in the supine position with his legs apart and his head tilted up 15 degrees to help lower central venous blood pressure. Dr. Kwon stood between the patient’s legs, with a view of the laparoscopic camera monitor placed in front of him, above the patient’s head. Surgeons Federico Aucejo, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Liver Cancer Program, and Cristiano Quintini, MD, Director of Liver Transplantation, assisted. Surgeon Kazunari Sasaki, MD, has extensive experience with the flexible 3-D laparoscope, so he was in charge of the camera.

Dr. Kwon prefers a 3-D scope rather than 2-D because it provides intuitive visual feedback with better depth perception. That may not be needed in simple surgeries such as cholecystectomy, but is essential in procedures as complex as living donor hepatectomy in order to perfect the operation.

In an adjacent operating room, Koji Hashimoto, MD, PhD, Director of LDLT, and surgeon Masato Fujiki, MD, prepared the transplant recipient.

Dr. Kwon placed five trocar ports: one 12 mm at the umbilicus for optics; two 12 mm operative trocars on either side of the optics port, mainly for use by the operator; a 12 mm trocar below the sternum for retraction and exposure; and a 5 mm trocar in the left anterior axillary line.

After mobilizing the donor liver by dividing the triangular, falciform and coronary ligaments and performing a cholecystectomy, Dr. Kwon gently dissected and clamped the hepatic artery and portal vein.

Fluorescent intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) cholangiography was used for real-time visualization, to delineate the left and right liver lobes for accurate parenchymal transection, and the bile duct anatomy for precise division. This advanced technique is based on the principle that intravenously injected ICG is excreted into bile and emits light when illuminated with a near-infrared light source coupled to the laparoscopic camera. The surgeon can alternate between normal and near-infrared views on the camera monitor.

After clamping, the differential in blood flow between the left and right liver creates a distinct demarcation line between the dark and light (fluorescing) halves, facilitating transection. Likewise, bile duct anatomy is clearly illuminated. “With that fluorescence, you see the bile duct a lot better than when it’s not lit up,” says Dr. Kwon.

Following bile duct division and clipping, Dr. Kwon completed the remaining liver parenchymal transection. He made a 9 cm Pfannenstiel incision in the donor’s abdomen through which to remove the graft, and inserted a plastic bag to contain it and aid handling. Placing the bag before dividing the hepatic artery reduces warm ischemia time.

Dr. Kwon notified the recipient’s surgical team that the donor liver segment would be ready for transplant in 10 minutes. After injecting heparin 3,000 IU intravenously, he double-clipped and divided the hepatic artery. The portal and hepatic veins were divided and the remnant stumps were sealed with one-sided staples. Dr. Kwon retrieved the graft through the incision, handed it off to the recipient team, then inserted drains and sutured the small abdominal opening.

Although large Asian medical centers have performed laparoscopic living donor hepatectomies in significant numbers, fewer than 30 have been undertaken in the United States for adult living donor liver transplant recipients. In addition to the aforementioned reasons — the formidable learning curve and the demand for dual-specialty surgical expertise — skepticism among U.S. transplant surgeons about the procedure’s feasibility in larger-sized American patients may also be a factor, Dr. Kwon believes. Successful transplants like Cleveland Clinic’s may help dispel that notion.

“I don’t dispute that large body sizes can create challenges for laparoscopic living donor cases,” he says. “The average BMI of donors in Korea is 23; in the U.S., it’s 28. The average graft size in Korea is around 720 grams; in the U.S. it’s 890. I understand that can present some difficulties. But I believe laparoscopic LDLT is feasible for any population in the world if you know how to do it properly.”

Eventually, Dr. Kwon hopes to establish an advanced laparoscopic liver and pancreas surgery training and educational program at Cleveland Clinic, to increase the number of surgeons who can undertake those procedures.

His goals for Cleveland Clinic’s laparoscopic living donor liver program are to build its volume, adding pediatric patients to the mix and performing the more-challenging right-lobe hepatectomy donor procedure.

“In a few years, I expect that we will have the largest program in the United States,” he says.

Advertisement

Benefits of neoadjuvant immunotherapy reflect emerging standard of care

Multidisciplinary framework ensures safe weight loss, prevents sarcopenia and enhances adherence

Study reveals key differences between antibiotics, but treatment decisions should still consider patient factors

Key points highlight the critical role of surveillance, as well as opportunities for further advancement in genetic counseling

Potentially cost-effective addition to standard GERD management in post-transplant patients

Findings could help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication recommendations

Insights from Dr. de Buck on his background, colorectal surgery and the future of IBD care

Retrospective analysis looks at data from more than 5000 patients across 40 years