Experts urge using ‘diagnosis uncertain’ and describing abnormalities instead

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/46938b56-3cf4-441b-a72f-6e80078b3de0/19-NEU-450-mitochondrion-650x450_jpg)

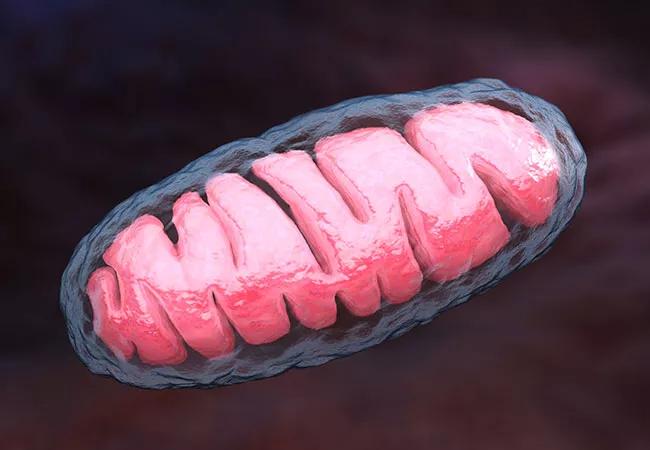

19-NEU-450-mitochondrion-650×450

For patients who have clinical and biochemical features of a mitochondrial disorder but are lacking a confirmed genetic abnormality, 25 mitochondrial disease experts from North America, Australia and Europe argue that the diagnosis of “possible” mitochondrial disease should be abandoned. This nonspecific label, they contend in a recent review article in the Journal of Medical Genetics (2019;56:123-130), may create unwarranted patient anxiety, delay continued evaluation and lead to inappropriate care.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Stick with what is known, and use the phrase ‘diagnosis uncertain’ with a description of clinical and biochemical abnormalities if a specific cause cannot be ascertained,” urges pediatric neurologist Sumit Parikh, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Mitochondrial Disease Center and lead author of the article. “That way, the patient’s condition will more likely be investigated further as it evolves and as newer tests become available.”

An estimated 1,000 to 4,000 children are born each year in the U.S. with a genetic mitochondrial disease. But possible signs and symptoms are highly variable, ranging from growth and developmental delay to autism-like features. A mitochondrial disorder can present with increased infections, thyroid problems or neurological issues, including seizures and stroke.

The field is also hampered by incomplete understanding of the relationship between the genome and mitochondrial function. Some 1,500 nuclear genes have been associated with mitochondrial function, but only about 350 of them have been linked to causing disease.

Criteria for diagnosing mitochondrial disease developed during a time of limited genetic testing, so diagnosis depended mainly on abnormal biochemical findings from tissue. This inevitably led to many patients being diagnosed with “possible” mitochondrial disease.

Now, with the advent of rapid, relatively inexpensive next-generation sequencing, a clear genetic diagnosis can be made in many patients with signs and symptoms of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Advertisement

Guidelines developed in 2015 by the Mitochondrial Medicine Society (Genet Med. 2015;17:689-701) detailed an efficient, standardized approach to evaluating suspected mitochondrial disease, which includes the following methods:

“Histopathological, biochemical and genetic analysis of tissue should no longer be considered first-line or even second-line tests if one strongly suspects a mitochondrial disease and appropriate genetic testing is available,” points out Dr. Parikh, who also led the international team of mitochondrial disease experts that developed the 2015 guidelines. “Although genetic testing clearly results in a diagnosis in only some cases — 25% to 75%, based on reports to date — clinicians must be extremely cautious before making a diagnosis based on biochemical tissue abnormalities alone.”

“Clear diagnostic labels are critical to good patient care,” adds Dr. Parikh. He and his co-authors also argue against use of the terms “mitochondrial myopathy” and “mitochondrial metabolism disorder” when a definitive diagnosis has not been established. When mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified but the underlying genetic problem has not, they prefer the phrases “genetic diagnosis uncertain” or “mitochondrial biochemical dysfunction [or genetic variant] of unknown significance identified.”

Advertisement

Vague terms that suggest a mitochondrial disease when it has not been definitively established can prematurely end diagnostic evaluation and miss potentially treatable conditions, Dr. Parikh explains. In addition, patients and parents of young children may endure years of worry about a progressive or degenerative disorder based on an incorrect diagnosis. Inappropriate risk counseling, preventive care, medications and reproductive decisions can ensue as a result.

He also notes that, over time, the “possible” qualifier may be dropped in the medical record as the patient continues to receive care, leading a once tentative diagnosis to become set in stone.

“With new testing modalities continuously being developed, a case of ‘possible’ mitochondrial disease may turn out to be identified as a non-mitochondrial genetic disorder down the road,” Dr. Parikh adds. “Prematurely ending the diagnostic journey for our patients by giving them an ambiguous diagnosis does them a great disservice.”

The full review article is available here.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Insights from one of the first studies of invasive monitoring in the rare form of focal cortical dysplasia

The disease’s neuropathologic heterogeneity holds clues to refining diagnosis and prognosis

A case study in pairing imaging acumen with subspecialty expertise to yield answers and symptom relief

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss