Study offers a foundation for additional research to examine radiation and immune response

A recent research effort—led by a team of Cleveland Clinic experts—explored radio-immune response modeling for cancer patients, shedding light on the effect radiation has on the immune response. These findings, which were recently published in the journal Physics in Medicine & Biology, lay the groundwork for future clinical trials.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

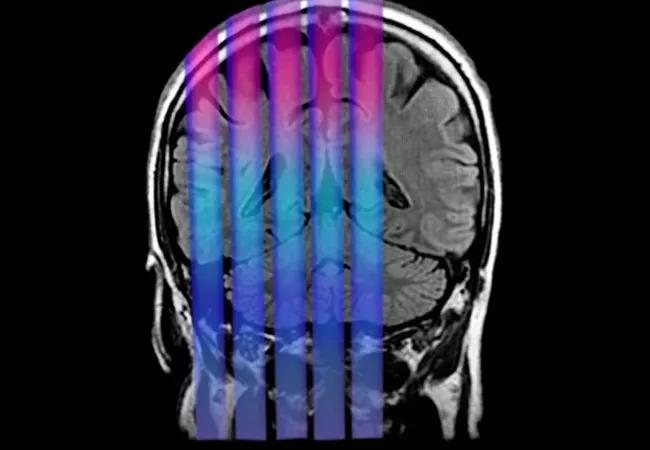

“There has been a renewed interest in spatially fractionated radiotherapy, historically known as GRID therapy,” says study author Jacob G. Scott, MD, DPhil, Department of Translational Hematology and Oncology Research at Cleveland Clinic. “Unlike the standard approach, spatially fractionated radiotherapy delivers highly heterogeneous dose distributions and has proven beneficial for large tumors that are typically difficult to treat with conventional radiotherapy.”

While previous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness, less is known about the “why” behind this approach, according to Dr. Scott. To address this knowledge gap, the Cleveland Clinic team, including Young-Bin Cho, PhD, Department of Radiation Oncology, developed a mathematical model that allows for deeper investigation of the immune process and its role in radiotherapy.

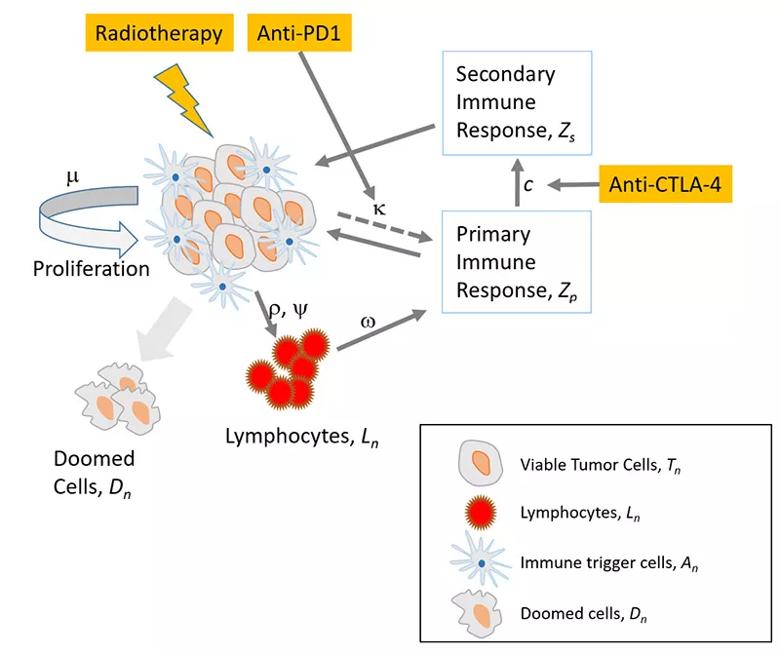

In this study, Dr. Cho and colleagues used existing models to create an ordinary differential equation model of tumor growth with radiation and the immune system. This new tumor model has four compartments: viable tumor cells, T-cell lymphocytes, immune triggering cells and doomed cells.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/80298a98-40b5-45f2-a6e6-803a7fb3bed6/23-CNR-4198921-CQD-Inset-800x670-1_jpg)

The researchers identified and analyzed two distinctive modes of tumor status—immune limited and immune escape. “Tumors in the immune limited mode can grow only up to a finite size,” explains Dr. Cho.

“The dynamics of the tumor growth in the immune escape mode is much more complex than the tumors in the immune limited mode, especially when the status of the tumor is close to the bifurcation condition,” Cho and his colleagues reported in their recent paper. “Radiation can kill tumor cells not only by radiation damage but also by boosting immune reaction.”

Advertisement

Using this model, the researchers showed that spatially fractionated radiotherapy can have a significant impact on tumor cell killing when compared to the more traditional homogeneous dose distribution approach.

“Spatially fractionated radiotherapy can not only enhance but also moderate the cell killing, depending on the immune response triggered by many factors, such as dose prescription parameters, tumor volume at the time of treatment and tumor characteristics,” notes Dr. Cho and team, who demonstrated this by applying their model to prior data on 67NR murine tumors as well as a sarcoma patient.

“Continuing to improve our understanding of the role and response of the immune system both during and following radiotherapy is crucial, says Dr. Scott. “Our model has the potential to help determine when novel methods, such as spatially fractionated radiotherapy, are warranted. Additionally, it could support efforts to amplify the synergistic effect of radiation and immunotherapies.”

This begins by delving deeper into the hypotheses produced by this study in regard to how radiation and the immune system interact. Dr. Cho and his colleagues plan to conduct laboratory studies to further explore this area of investigation. Another avenue of research involves taking a closer look at existing clinical data to validate the effectiveness of their mathematical model. Through these efforts, the research team hopes to take this model and move toward a clinical study.

“The interaction between radiation therapy and the immune system is a complex dynamic process,” says Dr. Cho. “Therefore, understanding the background mechanism is important to design successful clinical trials. Many studies have looked at static aspects of the immune response and do not provide a complete picture of the mechanism.“

Advertisement

“Our model, hopefully, can help us better understand the dynamic mechanism of the immune response, so that we and others can design more effective clinical trials in the future,” he concludes, while emphasizing that their model has a variety of implications not only for the use of spatially fractionated radiotherapy, but also more standard radiation approaches. “We are very excited to continue our work with this model and to better understand its potential impact on future research and clinical care.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

An update on the technology from the busiest Gamma Knife center in the Americas

Radiation oncology department finds weekly plan of care meetings have multiple benefits

Daily five-fraction partial breast irradiation (PBI) shows similar acute and late toxicity as every other day PBI

Number of stent layers correlates with worse outcomes

Research highlights promising outcomes for treating recurrent and metastatic cases

Improvements enable targeting of brain tumors with single-session, fractionated or neoadjuvant approaches

Correlation found between the biomarker HSD3B1 and resistance to combined hormone therapy and radiotherapy

Cleveland Clinic radiation oncologists aim to bring the noninvasive approach back to the U.S., where use has declined