Add it to your differential for atypical left flank pain

By Samuel Samuel, MD, and Bimal Patel, DO

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 38-year-old female presented with a 1.5 year history of left upper abdominal pain radiating to the left flank (7/10 on visual analog scale), nausea, early satiety, acid reflux, daily vomiting and significant weight loss. Her history was notable for gastroparesis and depression. During one of many hospitalizations for the pain, she underwent a C3-7 fixation surgery for severe cervical spine degenerative changes, but experienced no improvement in her abdominal pain. Moderate gastroparesis was found on a nuclear medicine study, but treatment did not improve her symptoms. Gabapentin, pregabalin, vitamin D and transcutaneous nerve stimulation all failed to relieve her pain.

We ordered an MRI of her thoracic spine, which was normal. We then performed a series of diagnostic left T9 paravertebral blocks to determine her pain’s origin with very minimal effect. Next, we tried a celiac plexus block. She experienced a week of total pain relief. Thus, our team in the Department of Pain Management went searching for a visceral origin of her pain.

A two-year-old CT from an outside hospital was discovered in her chart. It noted pancreatic head and uncinated process prominence and recommended advanced imaging. Our team ordered an MRI of the abdomen and pancreas, which revealed nutcracker phenomenon.

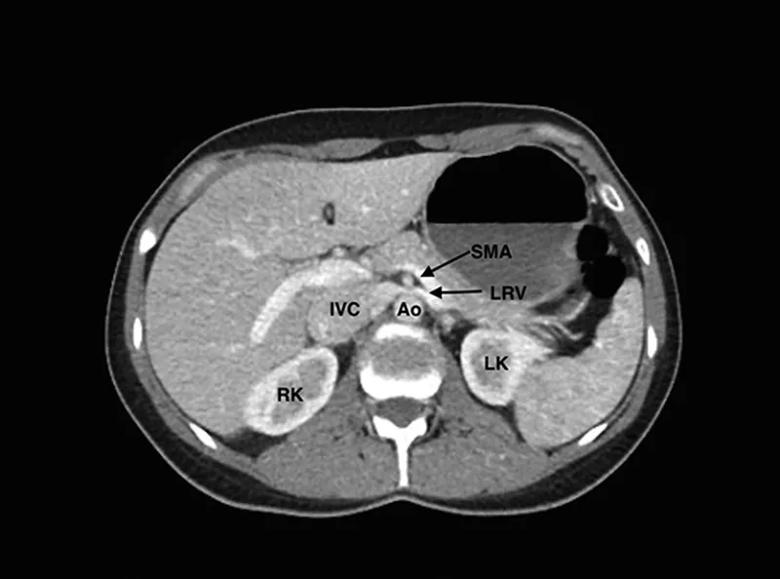

Nutcracker phenomenon is an uncommon condition characterized by compression of the left renal vein (LRV) between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), the SMA and aorta appearing as two arms of a “nutcracker” compressing the LRV. Patients with this anatomical disturbance can develop hematuria, varicoceles, flank pain and proteinuria. Increased pressure in the renal vasculature causes small veins in renal fornix to rupture, resulting in microhematuria. Data on prevalence are scarce, and definitive diagnostic criteria are lacking. Thought some patients are asymptomatic and don’t require treatment, many patients experience debilitating pain that requires aggressive intervention.

Advertisement

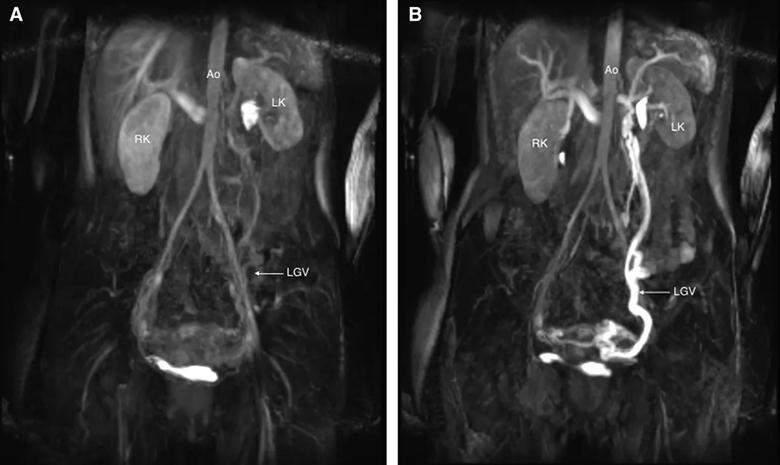

The MRI showed abrupt narrowing of the LRV between the aorta and SMA and a dilated left gonadal vein. A renal ultrasound revealed low monophasic flow proximally and elevated velocities between the aorta and SMA. We reviewed previous urinalyses and found several positive hematuria samples. Magnetic resonance venography confirmed compression of the LRV by the SMA and the aorta, which resulted in preferential contrast filling in the left gonadal vein.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/38e685f4-8576-44a5-b9ab-2b1f105e39b6/samuel-1_jpeg)

Computed tomography enterography scan. The left renal vein (LRV) is seen being compressed between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and Ao (aorta). IVC indicates inferior vena cava; LK, left kidney; RK, right kidney.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7cc95120-2f86-4d7a-ada9-c62bb1cef4de/samuel-2_jpeg)

A, Precontrast coronal still image of venous flow (magnetic resonance venogram). B, Postcontrast coronal still image of venous flow (magnetic resonance venogram). The bright signal seen from the left kidney to the left gonadal vein is outlined and represents left renal hilum and gonadal vein dilation. Ao indicates aorta; LGV, left gonadal vein; LK, left kidney; RK, right kidney.

The patient underwent autotransplantation of her left kidney to her right lower abdomen in order to relieve the compression. Upon discharge, her pain had reduced to 2/10 on the visual analog scale. At a six-month follow up visit, her pain score was 1/10, she had discontinued all pain medications and was unrestricted in her daily activities.

Diagnostic blocks were critical in the cracking of this case, which we published in A & A Practice. The celiac plexus block allowed us to pinpoint the origin of pain as visceral, and the lack of relief from the paravertebral block made somatic abdominal wall pain a less likely cause.

Advertisement

In younger patients, pain often resolves because an increase in intraabdominal fibrous tissue in the SMA with growth releases the obstruction of the LRV. Weight gain can also change the position of the left kidney and increase retroperitoneal fat, relieving tensions on the LRV.

For patients with debilitating pain or those who require red blood cell transfusions due to nutcracker phenomenon-induced anemia, intervention is key. Several surgical options are available, including resection of fibrous tissue and placement of a wedge at the aortomesenteric angle, renocaval reimplantation, autotransplantation, LRV transposition and laparoscopic splenorenal vein ligation. Percutaneous endovascular stenting of the LRV has shown long-term symptom resolution as well.

As pain management specialists, we should include nutcracker syndrome in the differential when the symptoms indicate, and not simply assume atypical left flank pain is chronic myofascial or due to lower rib pathology.

Dr. Samuel directs the pain management clinic at Marymount Hospital and is a pain management specialist at Cleveland Clinic main campus. Dr. Patel is a fellow in the Anesthesiology Institute.

Images and captions republished with permission from the International Anesthesia Research Society.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researchers seek solutions to siloed care, missed diagnoses and limited access to trauma-informed therapies

Study participants also reported better sleep quality and reduced use of pain medications

Two-hour training helps patients expand skills that return a sense of control

Program enhances cooperation between traditional and non-pharmacologic care

National Institutes of Health grant supports Cleveland Clinic study of first mechanism-guided therapy for CRPS

Pain specialists can play a role in identifying surgical candidates

Individual needs should be matched to technological features

New technologies and tools offer hope for fuller understanding