Compassion, communication and critical thinking are key

Researchers seek solutions to siloed care, missed diagnoses and limited access to trauma-informed therapies

Study participants also reported better sleep quality and reduced use of pain medications

Two-hour training helps patients expand skills that return a sense of control

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Telehealth aids in treatment of fibromyalgia and median arcuate ligament syndrome

Spinal cord stimulation can help those who are optimized for success

Program enhances cooperation between traditional and non-pharmacologic care

National Institutes of Health grant supports Cleveland Clinic study of first mechanism-guided therapy for CRPS

Patients report improved sense of smell and taste

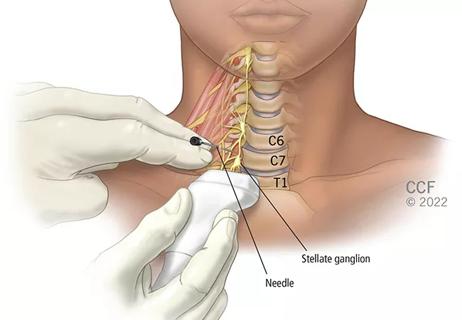

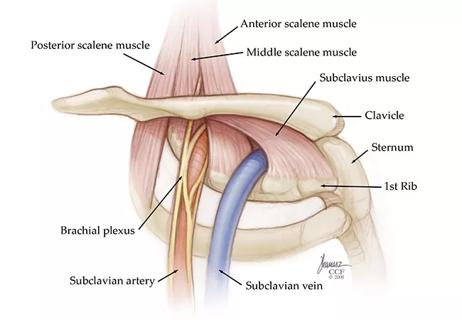

Pain specialists can play a role in identifying surgical candidates

Advertisement

Advertisement