Novel approach begins reinnervation before tumor resection, preserving a young woman’s smile

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f9735d2d-79b9-4ccc-b276-da5ee9bd4d24/facial-nerve-rewiring)

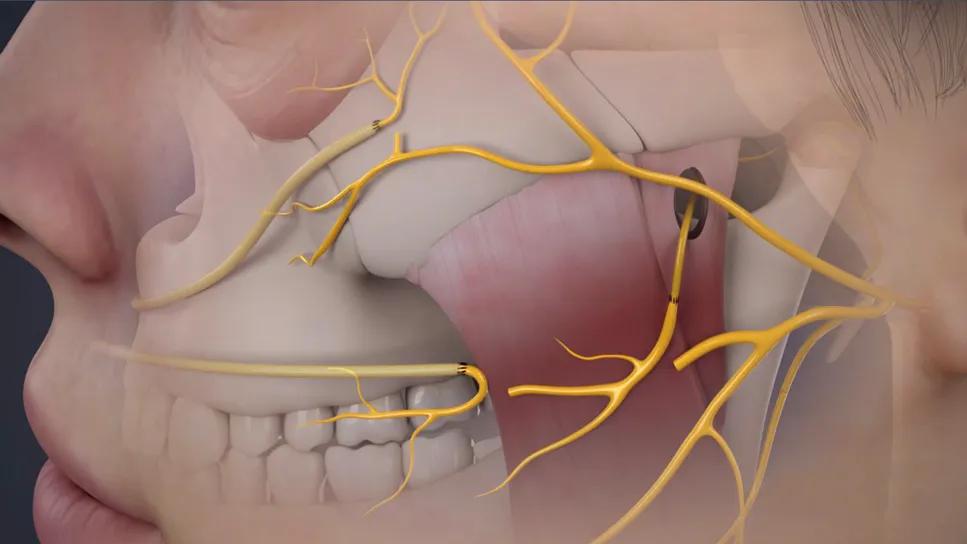

network of nerves on the side of the face

A 13-year-old girl from Michigan presented to Cleveland Clinic skull base neurosurgeon Pablo Recinos, MD, in 2018 for a second opinion.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

She had recently developed a constant “strange pulsing noise” in her left ear diagnosed as pulsatile tinnitus. CT evaluation by her local physicians revealed a growth behind her left eardrum that was diagnosed as facial nerve schwannoma. Although such tumors are benign and slow growing, the girl’s local providers recommended swift surgery to resect the tumor to prevent later complications. But they advised the patient and her parents that the surgery would paralyze the left side of her face and compromise hearing in her left ear. This prompted the family to seek a second opinion at Cleveland Clinic.

Upon examination, Dr. Recinos agreed that the case was consistent with a facial nerve schwannoma, but he advised the family that tumor resection could likely be delayed in an effort to buy time for a solution that might preserve the girl’s facial function and hearing.

“The patient was young, and her tumor was small and not showing signs of growth,” Dr. Recinos explains. “It wasn’t pressing on the brain or causing any effects beyond the pulsatile tinnitus. I told the family that these types of tumors don’t always grow in a linear pattern, and that hers might not grow for a while. There was no need to rush into a surgery that would have devastating effects on the patient’s facial function and appearance at such a formative age.”

Indeed, conventional management with immediate resection of the tumor would have caused total left-side facial paralysis, including an inability to blink the eye and drooling from the left side of the mouth. Resection would be followed by facial nerve reinnervation surgery, but the start of any resulting improvement in facial nerve function would take a minimum of six months, relegating the patient to complete left-side facial paralysis for at least that long, even if reinnervation surgery were done right away. Moreover, reinnervation following tumor resection can restore facial function only partially, leaving the family with great uncertainty about the ultimate outcome.

Advertisement

Dr. Recinos raised the potential option of Gamma Knife® stereotactic radiosurgery, but he and the family decided not to pursue it at the time since the tumor wasn’t growing much and it wouldn’t yield the definitive tumor removal needed as a lifelong solution for this very young patient.

They settled on a strategy of careful surveillance to monitor for tumor growth and facial nerve weakness and then respond accordingly. Monitoring consisted of MRIs every six months along with regular clinical examinations.

Over the next two to three years, the patient’s condition remained relatively stable even as the management plan advanced with a significant new development.

Dr. Recinos enlisted the assistance of leading facial reanimation surgeon Patrick Byrne, MD, MBA, soon after Dr. Byrne joined Cleveland Clinic in 2020. At his prior institution, Dr. Byrne and a colleague had begun developing a novel approach involving preemptive reinnervation procedures prior to definitive management of a facial nerve tumor.

“In the facial reanimation field, we recognized a number of years ago that there is a reinnervation window, or a period after deinnervation before it is too late to reinnervate,” explains Dr. Byrne, Chief of Cleveland Clinic’s Integrated Surgical Institute and Chair of the Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery. “This is the period before there is so much atrophy of the muscles into which the nerves’ motor end plates feed that movement is no longer possible.”

Early in his career, Dr. Byrne had another important realization. “I came to recognize that there wasn’t much of a penalty for performing nerve transfers that reroute facial nerves,” he says. “We could reroute a chewing nerve, and the patient could still chew just fine. We could reroute a portion of the nerve that moves the tongue, and the patient could speak just fine. We could use a facial nerve branch from the other side of the face, and that side would smile just fine. This insight opened up options for a variety of conditions.”

Advertisement

One of them was facial nerve tumors, for which Dr. Byrne and his colleagues began to consider the notion of preemptive “rewiring” of the facial nerves prior to tumor resection. “We realized that these cases sometimes involve a period of time when the skull-base surgeon and patient are figuring out what to do,” Dr. Byrne explains. “We wanted to take advantage of that time by rewiring part of the face through a nerve transfer, giving the nerve time to reinnervate before tumor removal. This would set up the patient for less loss of nerve function after resection.”

Dr. Byrne and his colleagues applied this approach in a very small number of patients over two to three years before he came to Cleveland Clinic, with promising results.

When Drs. Recinos and Byrne explained the preemptive facial rewiring approach to the patient and her family, they were receptive to the idea. The plan was to begin intervening once the patient began showing facial nerve weakness.

In March 2021, when the patient was in 11th grade, she began manifesting some facial asymmetry and mild facial paralysis. That prompted the start of the facial rewiring surgery. “As a tumor grows along the facial nerve, it will make the nerve progressively weaker,” Dr. Recinos says. “It was doing that, so we wanted to start the rewiring before the muscles atrophied.”

In June 2021, Dr. Byrne performed a masseteric facial nerve transfer, connecting the facial nerve to the masseter branch of the trigeminal nerve. “The masseter nerve is a powerful chewing nerve that drives movement,” he explains. “The patient wanted support for her smile and help with her eyelid tone, so we chose a recipient nerve we expected to accomplish both, which it did.”

Advertisement

This was followed by a second operation in late 2022 to place two right-to-left cross-face nerve grafts. Grafts of the sural nerve, a sensory nerve in the lower leg, were harvested to connect the facial nerve on the right side of the face to the buccal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve on the left side. “Cross-face nerve grafting is very helpful because it can provide spontaneity,” Dr. Byrne notes. “Our other nerve transfers don’t always do so.”

Dr. Byrne says the rewiring procedures completed across these two operations (Video 1) are the same ones that would be used for traditional reinnervation after facial nerve tumor resection; the only novel element was their preemptive nature. He adds that he would have normally performed the procedures in a single operation but that the patient’s family wanted to proceed gradually. “The whole experience was a bit overwhelming to them, so we took it in smaller steps,” he says.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_e2nr5z7p/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Video 1. Animation showing the cross-face nerve grafting in this case.

The rewiring procedures — plus some facial physical therapy after the cross-face nerve grafting — yielded improvement in the patient’s facial asymmetry and paralysis, which had progressed to prevent her left eye from closing properly.

This improvement allowed the patient to finish high school and begin college without further intervention. “We were comfortable continuing to wait for tumor resection, as this period was allowing the nerve rewiring to solidify and fully take hold,” Dr. Recinos says.

Eventually the patient did develop new facial nerve weakness and began experiencing headaches. Her MRI in December 2023 revealed significant tumor growth to the point that it was approaching the brain stem (Figure 1). “The growth was at such a clip that it was clearly time to start planning the resection surgery,” Dr. Recinos notes.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/dca3bf8f-f528-40f8-ae2e-fd0cfbf70f16/facial-nerve-rewiring-inset-1)

Figure 1. MRIs from December 2023, eight months before tumor resection. The peach-colored region is the tumor, located in the middle cranial fossa and extending into the internal acoustic canal. Note the proximity to the carotid artery, shown by the red dot.

Tumor resection took place in early August 2024. The 20-hour operation involved middle fossa craniotomy combined with a transpetrosal approach. Neurotologist Anh Nguyen-Huynh, MD, created access to the tumor above the temporal bone. The team then gently elevated the brain to enable resection of the entire tumor, along with the damaged portion of facial nerve, by Dr. Recinos. Then Dr. Byrne harvested a portion of the great auricular nerve to replace the nerve segment resected with the tumor, and he grafted the hypoglossal nerve onto the facial nerve to provide additional support and complete the rewiring process (Video 2).

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_7x7dnmia/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Video 2. Animation showing resection of tumor and damaged nerve.

Prior to the operation, the patient and her family had been told she might still lose some hearing and facial function after the resection. Upon awakening from anesthesia, she was able to hear in both ears and had no trouble speaking. Her facial function was also largely intact (Figure 2): Several days after surgery, the left side of her mouth was curving back to its normal position and her left eyelid was closing better than before surgery. Her pulsatile tinnitus was gone for the first time in over six years.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/51c949b8-8b55-463f-b4a4-937d25938d06/facial-nerve-rewiring-inset-2)

Figure 2. The patient before any facial weakness developed (left), after her first nerve graft surgery (second from left), six months after her second nerve graft surgery (second from right) and shortly after tumor resection (right).

“Seeing her facial function a day or two after surgery was amazing,” Dr. Byrne says. “She did have some facial weakness, but the difference from the paralysis she would have had with the traditional approach was profound.”

To build on her gains, the patient soon began a specialized form of physical therapy called facial retraining that will continue for at least six months. “Facial retraining is very, very important in a case like this,” Dr. Byrne says. “Through steady and conscious practice, her central nervous system is rewiring so that she develops a sort of muscle memory and eventually won’t need to consciously clench her jaw or press her tongue against the back of her teeth. Facial retraining helps patients augment and continue their functional improvement, including the critical function of communicating emotion through the face. Steady improvement can be expected for at least two or three years.”

He notes that Cleveland Clinic is one of very few centers in the nation with multiple therapists who specialize in facial nerve rehabilitation.

The patient’s hearing loss in her left ear was approximately 35% several months after tumor resection, a level that “can be readily compensated by a hearing aid,” says Dr. Nguyen-Huynh. “Her hearing outcome is remarkable given the size of the tumor and the extent of the surgery.”

Tissue sampling at the time of resection confirmed that the tumor was completely excised. It also revealed a final surprise from the case: the tumor was actually a meningioma, not the long-suspected schwannoma.

“This was a shock,” says Dr. Recinos, “because the tumor had coursed along the facial nerve just as schwannomas do. It showed all the classic behavior of a schwannoma, including causing facial nerve weakness, which meningiomas don’t typically cause.” Despite the surprise, he said his recommended management wouldn’t have changed had he known up front that the tumor was a meningioma.

The patient’s prognosis is good, with the chief remaining concern being the possibility of tumor recurrence, for which she will undergo active MRI surveillance.

The prognosis for this novel treatment approach is equally good. While this was the first facial nerve tumor patient to undergo preemptive facial nerve rewiring at Cleveland Clinic, Drs. Recinos and Byrne have since initiated the strategy in several more patients.

Dr. Byrne is aware of no literature reports or case presentations on the treatment strategy, although he is working on a manuscript reporting his early experience with the approach. He believes it has strong potential for widespread adoption. “Preemptive facial nerve rewiring offers the chance to prevent the devastating facial paralysis that comes at least temporarily with the conventional approach to these cases,” he says. “And it likely delivers a better long-term result as well. Who wouldn’t want that?”

Both Drs. Recinos and Byrne believe this new approach is particularly well suited to the integrated multidisciplinary care model practiced at Cleveland Clinic.

“Our model promotes a synergistic approach to care that allows for the thoughtfulness that made this case possible,” Dr. Recinos says. “Our experts have a comfort and familiarity with their counterparts in other disciplines to occasionally stray from our lanes if it can make a difference for a patient. That allowed each of us to take the other’s area of focus into account — be it the tumor’s natural history or the factors involved in reinnervating a face — to develop a much better plan for the patient. That level of collaboration is hard to find.”

Advertisement

Multidisciplinary perspectives on the importance of early referral and more

Despite advancements in the specialty, patient-centered care needs to remain a priority

Findings could help with management of a common, dose-limiting side effect

Novel therapy “retrains” the brain to disrupt pain signals

The tri-vector gracilis procedure uses a thin muscle from the thigh to help create a natural mimetic smile

A review of takeaways from the recent U.K. national guidelines

Spinal cord stimulation can help those who are optimized for success

Findings suggest new ways to improve outcomes