Insights into the choice between craniotomy and endoscopic endonasal approaches

Patient A was a 36-year-old woman who presented to Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute reporting right-sided facial numbness and pain of nearly three years’ duration. Her symptoms began as intermittent numbness and tingling over the right eye but intensified over time into searing pain often triggered by yawning, chewing or laughing. She also developed jaw spasms and near-constant headaches. MRI revealed a large tumor pressing on the trigeminal nerve and extending from the intracranial space toward the brainstem.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

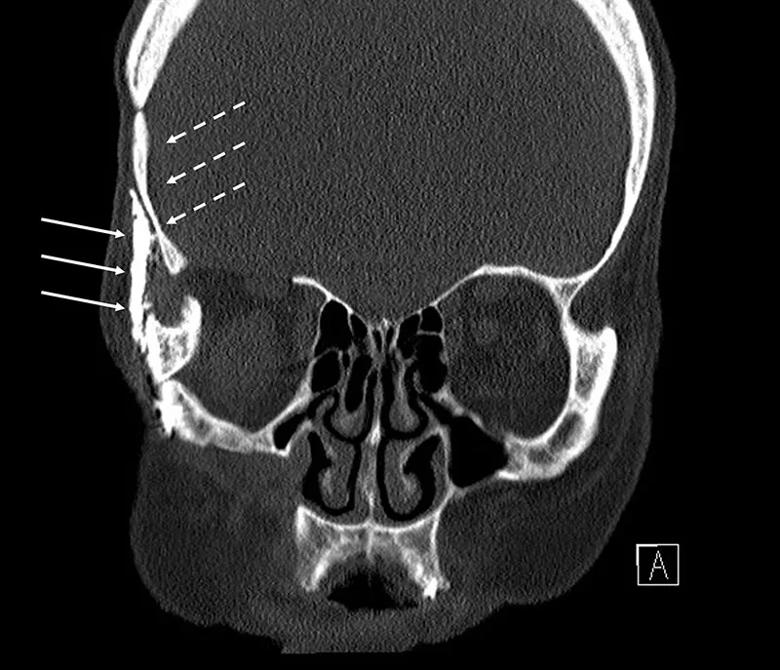

Patient B was a 64-year-old woman who presented to Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute with long-standing mild facial numbness and jaw weakness. She had undergone four surgeries for trigeminal schwannoma over the prior three decades, all at outside institutions. The first two operations were craniotomies performed 32 years earlier. Schwannoma recurrence prompted a third craniotomy 10 years later (Figure 1). A subsequent recurrence further along the trigeminal nerve prompted the fourth operation 15 years after that and seven years before her current presentation. The fourth operation was an open craniofacial procedure involving incisions behind the hairline at the temple, on the outer aspect of the eye socket, and around the nose and under the eyelid (Figure 1). Imaging at the time of the fourth operation revealed aspects of the tumor closer to the nose that could not be accessed in the open procedure. Subsequent imaging over the ensuing seven years showed progressive tumor growth from that site — specifically arising from the foramen rotundum and extending from the skull base down into the pterygopalatine fossa.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/981d32fd-9872-489d-a7f0-3b3fae94b1d3/22-NEU-2826664-CQD-Inset-Fig1-800x687-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Preoperative CT of Patient B showing evidence of prior craniotomy (dotted arrows) and the open craniofacial approach (solid arrows).

Although quite different in age and history, both patients were diagnosed with trigeminal schwannoma, an almost always benign tumor of the peripheral intracranial nerve sheath originating from Schwann cells. Trigeminal schwannomas are rare, representing no more than 0.3% of intracranial tumors and about 1% to 5% of intracranial schwannomas.

Advertisement

These tumors may arise at any point along the three-branched trigeminal nerve, with the location of symptoms — from forehead to lower jaw — varying based on where the tumor arises. Symptoms can affect the nerve’s sensory function, manifesting as numbness or pain from pressure exerted by the tumor, as well as its motor function, causing difficulty chewing or jaw stiffness. Pain symptoms can range from lancinating pain to migraine-like headaches and thus overlap with those of trigeminal neuralgia. As a result, MRI is often needed to differentiate trigeminal schwannoma from trigeminal neuralgia.

Trigeminal schwannomas show variable growth patterns, with many tumors growing linearly by 2 to 3 mm per year while others grow faster and some remain dormant. Treatment options include the following:

Because almost all intracranial trigeminal schwannomas are benign, treatment timing and type depend on the size and/or growth rate of the tumor and the presence and severity of symptoms. Surgery is reserved for tumors that are larger, show aggressive growth or are associated with symptoms with significant impact on quality of life.

Upon her diagnosis of trigeminal schwannoma, Patient A was evaluated by neurosurgeon Pablo Recinos, MD, Section Head of Skull Base Surgery at Cleveland Clinic, who explained her treatment options. “I told her she could wait for serial imaging so we could determine whether and how much the tumor was growing,” he explains. “But I noted that her symptom progression over nearly three years suggested the tumor was likely growing and that growth at some point was highly likely, given her young age, with the possibility of affecting other critical functions such as hearing if it reached the brainstem.” This, together with the impact of her symptoms on her quality of life, convinced Patient A to pursue treatment.

Advertisement

“As in all cases of trigeminal schwannoma,” Dr. Recinos notes, “I took care to advise her that intervening carried some risk of continued numbness and other symptoms in addition to the much greater likelihood of symptom improvement or resolution. It’s important that patients be cognizant of this potential tradeoff before proceeding.”

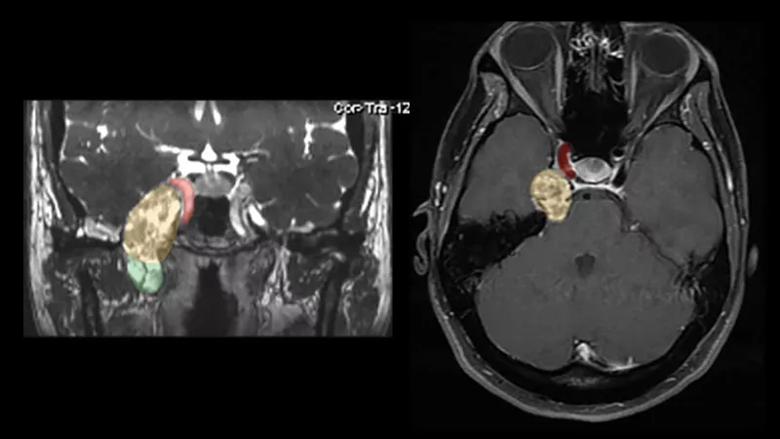

Patient A’s tumor was too large to be optimally amenable to radiosurgery, so Dr. Recinos considered the two surgical options: craniotomy or an endoscopic endonasal procedure. Because her MRI showed the tumor to have both intracranial and extracranial components (Figure 2), both options were reasonable possibilities.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2379a81a-cea2-4b6f-ab97-f96972297a64/22-NEU-2826664-CQD-Inset-Figure2-800x450-1_jpg)

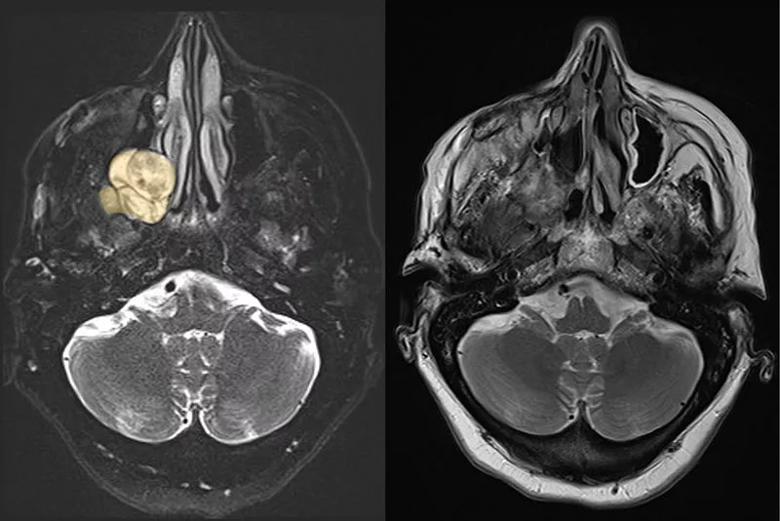

Figure 2. Preoperative MRIs of Patient A: a coronal CISS (constructive interference in steady state) image on the left and an axial T1 post-contrast image on the right. The images demonstrate a large enhancing tumor with a visible intracranial portion (yellow/orange area) and an extracranial component (green area) below the foramen rotundum extending down into the infratemporal fossa. The tumor abuts the right carotid artery (red area) as well as extending to the brainstem.

“An endonasal approach would be very well suited to removal of the portion of the tumor that was extracranial and in Meckel’s cave, where the trigeminal ganglion sits,” Dr. Recinos notes, “but it would be more difficult to access the portion along the carotid artery and brainstem, where we would probably need to leave some residual tumor. At the same time, whereas the intracranial portion of the tumor would be readily resectable via craniotomy, it was unclear whether craniotomy would allow resection of all of the extracranial portion in the infratemporal fossa. Each approach had limitations.”

Advertisement

Ultimately, he and his team decided to prioritize the section of tumor most easily addressed by craniotomy — i.e., the portion pushing on the carotid and brainstem. “That was the more critical area to treat thoroughly,” he says. “If craniotomy required us to leave some residual tumor down in the infratemporal fossa, that area was less critical and could be monitored and treated later, with radiosurgery or a second endonasal surgery, if necessary.”

Dr. Recinos performed a right skull base craniotomy by making an opening in the anterior petrous apex to pass from the middle fossa to the posterior fossa. He and his team used a variety of microdissection instruments under high-power microscopic magnification to remove the tumor piece by piece, relying on an ultrasonic aspirator to dissect and remove even the hard-to-reach sections he had initially feared might not be accessible. They took care to identify and avoid fascicles of normal nerve on the tumor surface. “Preservation of normal fascicles is critical to protecting the patient’s sensation and functional abilities like chewing,” he explains.

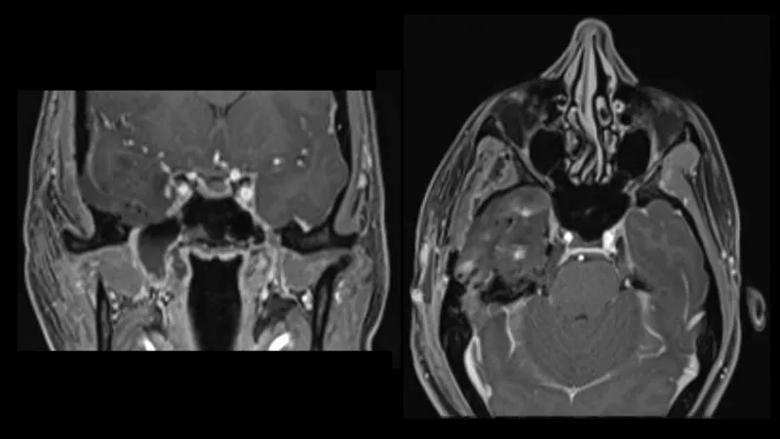

By using the corridor the tumor had created, the team was able to also remove the extracranial component of the tumor to achieve a gross total resection of both intra- and extracranial components (Figure 3). They then sealed the operative site with a dural substitute over the floor of the skull base, providing a new barrier between the intracranial and extracranial spaces. The operation lasted nine hours, and the patient was discharged home after four days in the hospital. Pathology confirmed that the tumor was benign.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/82485223-b84f-4101-94d3-077ede8718f4/22-NEU-2826664-CQD-Inset-Figure3-800x450-1_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative coronal (left) and axial (right) T1 post-contrast MRIs of Patient A demonstrating gross total resection of both the intracranial and extracranial portions of the tumor.

At six-week follow-up, the patient had complete resolution of her pain symptoms and jaw spasms. She reported gradual improvement of facial sensation, with about 90% restoration in her upper face and 60% restoration around the lower jaw. “I expect continued improvement in sensation with time, as nerves of the trigeminal branches heal at a rate of about an inch per month,” Dr. Recinos says.

The patient was pleased with the cosmetic results as well (Figure 4). Her lengthy incision — requiring 40 staples to close — was made narrowly along the hairline so that when she wears her hair down, it fully covers the scar.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ce57689e-0736-4f5e-9891-5ec3a4760853/22-NEU-2826664-CQD-Inset-Figure4-800x900-1_jpg)

Figure 4. Patient A (with her son) following recovery from her craniotomy. The lengthy incision was made along her hairline so that the scar can be fully covered by her hair. A personal profile of this patient’s case is available here.

For Patient B, the case for treatment was essentially about tumor growth rather than symptoms, notes the neurosurgeon who evaluated her, Varun Kshettry, MD. “She reported her facial numbness as mild, and her jaw weakness was likely a manifestation of all her prior open surgeries,” says Dr. Kshettry, a staff physician in Cleveland Clinic’s Section of Skull Base Surgery. “It was the continued growth of the tumor we saw on her serial MRIs over the prior seven years — at a rate of 2 to 3 mm per year — that suggested likely further problems in the next five to 10 years. Because of that, the patient had a preference to get this treated, especially when she learned it might be treatable in a different way from her past surgeries — endonasally.”

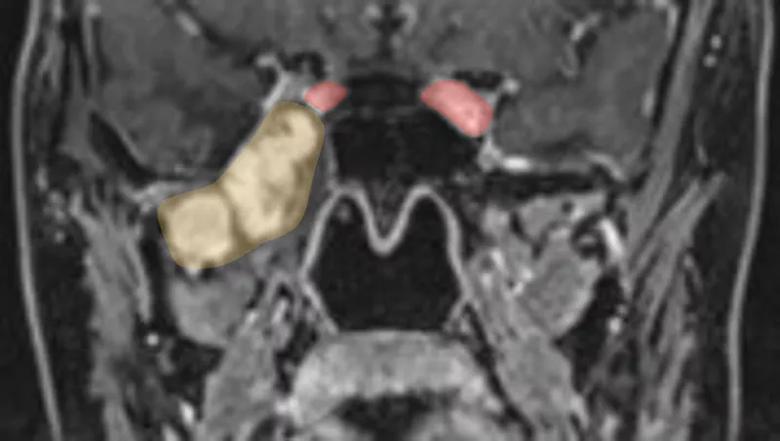

Dr. Kshettry reviewed Patient B’s imaging with rhinologic surgeon Raj Sindwani, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Head & Neck Institute. “We felt we could access all of the tumor using an endoscopic endonasal approach through both nostrils,” Dr. Kshettry says. “Not only was this likely to achieve our resection goals, but it would avoid reopening the multiple incisions from her past surgeries, which could risk poor healing and infection. Of course, an endoscopic approach also promised to reduce the patient’s postoperative pain and recovery time.”

Drs. Kshettry and Sindwani undertook the four-hour endonasal procedure together, opening up the back wall of the maxillary sinus from inside the nose to expose the pterygopalatine fossa (Figure 5). “That was ground zero for the majority of the tumor,” Dr. Kshettry explains. “From there, we were able to chase the tumor up to the foramen rotundum at the skull base and accomplish complete tumor removal” (Figure 6).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2d287547-767b-4a30-8096-8697c64a8e78/22-NEU-2826664-CQD-Inset-Fig5-800x452-2_jpg)

Figure 5. Preoperative coronal MRI of Patient B demonstrating a large enhancing tumor (yellow/orange area) arising from the foramen rotundum and extending down into the pterygopalatine fossa and infratemporal fossa. The tumor abuts the right carotid artery (red area).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4294cc13-9074-427b-9ca4-0670c1b6c057/22-NEU-2826664-CQD-Inset-Fig6-800x534-1_jpg)

Figure 6. Left: Preoperative axial T2 MRI of Patient B demonstrating T2 hyperintense tumor and its relationship with the nasal cavity. Right: Postoperative axial T2 MRI demonstrating complete tumor removal.

Owing to the less-invasive nature of the approach, the patient was discharged home the next morning and returned to her usual daily activities within a couple of weeks. Her initial congestion and anosmia — common postoperative effects of endonasal surgery — were gone by six-week follow-up, as were her occasional feelings of nasal dryness. The patient’s jaw weakness and mild numbness persisted, “but that was expected, as we had advised her that those likely were effects of her many prior surgeries that would not be addressed by complete tumor removal,” Dr. Kshettry notes.

“The reason for intervening in this case was not to address specific symptoms, none of which were of major concern to the patient,” he adds. “The reason was to remove the remaining tumor to prevent its continuing growth, which was likely to cause bigger problems in a few years. I suspect her postoperative MRI was probably the first clean MRI she has had.”

He adds that her prognosis is good, although she remains at risk of recurrence. For that reason, her Cleveland Clinic care team has recommended annual MRI surveillance as well as genetic testing to assess for an indolent underlying genetic disorder, given the unusual nature of her decades-long case involving multiple recurrences along the course of the trigeminal nerve.

Given the rarity of trigeminal schwannoma, Drs. Recinos and Kshettry each treat only about one to two cases a year. All endonasal procedures for the condition are performed by both a neurosurgeon and a rhinologic or sinus surgeon. “This is not typical sinus surgery that can be done with two hands,” Dr. Kshettry notes. “Because of the delicate structures involved in skull base sinus surgery of this type, three or four hands must be in the field working simultaneously.”

The surgeons say they have treated trigeminal schwannoma more often with craniotomy than with an endonasal approach. “That’s partly because symptoms tend to be greater from tumors that occur further back toward the brain, which are more amenable to craniotomy, as opposed to the back of the nose, which are more amenable to an endonasal approach,” Dr. Kshettry observes.

In fact, location of the tumor — particularly whether it lies in the intracranial compartment, the extracranial compartment or both — is the primary driver of the choice of surgical approach. Intracranial tumors are generally more accessible by craniotomy, and extracranial tumors are generally more accessible endonasally. “Each can be approached the other way, and occasionally certain circumstances might dictate a different choice, but in most cases these are the least disruptive ways to get the best access to tumors in these respective locations,” Dr. Recinos says.

Tumors that span both the intracranial and extracranial compartments, as was the case with Patient A, can be approached with either method. “In those cases it’s a matter of what other anatomic structures are nearby,” Dr. Recinos explains. “Will you need to elevate brain? If you go with a craniotomy, will you be able to do some maneuvers to minimize brain retraction? If you go through the nose, will you need to remove an inordinate amount of bone at the skull base, which would prolong the surgery? These are the issues we weigh with tumors that span both compartments.”

Another factor impacting choice of surgical option is the direction in which the tumor is pushing the nerve fiber bundles, which is generally clear from advanced imaging studies. “With craniotomy, you are coming from outside in, whereas with an endonasal procedure you are coming from the inside out,” Dr. Recinos says. “It’s a secondary consideration, but it’s preferable to coordinate the direction of your approach with how the nerve fibers are being directed.”

A final key factor is the experience of the surgeon and the treating center. “Some centers may have limited experience with one option or the other, which may influence their recommendations to patients,” says Dr. Kshettry, who notes that may have contributed to the incomplete tumor removal in Patient B’s most recent prior surgery. “The ideal is for a center to have what we call 360-degree skull base surgery offerings, where they have the experience and capabilities to offer options that can approach the tumor from any direction within the head, whatever the pathology may be.”

Advertisement

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Rapid innovation is shaping the deep brain stimulation landscape

Study shows short-term behavioral training can yield objective and subjective gains

How we’re efficiently educating patients and care partners about treatment goals, logistics, risks and benefits

An expert’s take on evolving challenges, treatments and responsibilities through early adulthood

Comorbidities and medical complexity underlie far more deaths than SUDEP does

Novel Cleveland Clinic project is fueled by a $1 million NIH grant

Tool helps patients understand when to ask for help