Investigational gene approaches offer hope for a therapeutically challenging condition

Podcast content: This podcast is available to listen to online.

Listen to podcast online (https://www.buzzsprout.com/2243576/15707148)

Despite recent therapeutic advances, about 30% of epilepsy cases remain pharmacoresistant. Among these medically intractable epilepsy cases, those involving temporal lobe epilepsy are among the most difficult to treat.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Temporal lobe epilepsy, particularly mesial temporal lobe epilepsy due to hippocampal sclerosis, was one of the first targets of surgical treatment for epilepsy,” says Imad Najm, MD, Director of the Epilepsy Center at Cleveland Clinic. “Yet even under the best conditions at the most experienced centers, treatment success with resective surgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy remains around 60% to 65%. Even though we often think of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy as unilateral, in many of the unsuccessful surgical cases seizures come back from the other side, and we cannot do surgery on both sides.”

In the latest episode of Cleveland Clinic’s Neuro Pathways podcast, Dr. Najm offers context on the challenges of these highly refractory cases of temporal lobe epilepsy and emerging efforts to overcome them with gene therapy. He covers the following topics, among others:

Click the podcast player above to listen to the 30-minute episode now, or read on for a short edited excerpt. Check out more Neuro Pathways episodes at clevelandclinic.org/neuropodcast or wherever you get your podcasts.

Advertisement

This activity has been approved for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ and ANCC contact hours. After listening to the podcast, you can claim your credit here.

Imad Najm, MD: The cancer field is about 20 years ahead of epilepsy when it comes to gene therapy. That’s because mutations have been found in some cancers that are very focal and very particular for the pathologies being treated. In epilepsy, most patients do not have a single pathological gene mutation. We have more studies showing something that we call polygenic changes, or multiple genes showing multiple mutations. None of these are pathological on their own, but collectively it seems like they increase the risk of epilepsy development.

Because of that, gene therapy in the context of focal epilepsies and even generalized epilepsies has not begun to catch up until recently. Over the past 10 to 15 years, we have started to see what we call somatic gene mutations in some focal pathologies in the brain, such as focal malformation of cortical development, or focal cortical dysplasia. These mutations are very much focal or restricted to the pathology, and these genes are part of pathways that are essential for axonogenesis, neurogenesis and synaptogenesis in epilepsy, as well as the plasticity and long-term potentiation leading to excitotoxicity.

These pathways seem to be significantly activated in focal cortical dysplasias, leading potentially to transformation of a pro-epileptic pathology to an active epilepsy focus. Although we cannot verify this 100% yet, there are some supportive preclinical models. This gives us hope that perhaps if we can target multiple genes at multiple levels of these pathways, we may be able to develop something to control these issues.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Novel Cleveland Clinic project is fueled by a $1 million NIH grant

Patients with epilepsy should be screened for sleep issues

Sustained remission of seizures and neurocognitive dysfunction subsequently maintained with cannabidiol monotherapy

Model relies on analysis of peri-ictal scalp EEG data, promising wide applicability

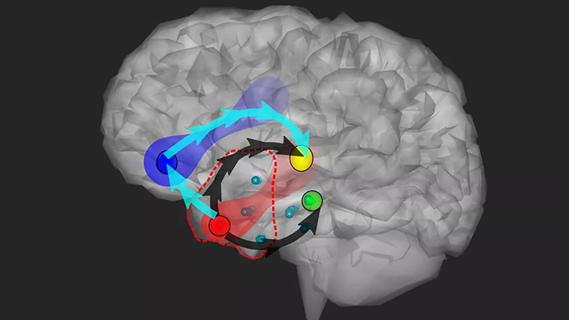

Study combines intracranial electrophysiology and SPECT to elucidate the role of hypoperfusion

Characterizing genetic architecture of clinical subtypes may accelerate targeted therapy

Data-driven methods may improve seizure localization and refine surgical decision-making

Pre-retirement reflections from a pioneering clinician, researcher and educator