Two trials provide important advances in treatment

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The results from two studies examining abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) in giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis (TAK) were recently published in Arthritis and Rheumatology. These trials were conducted by the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium (VCRC) and funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS).* The results from these studies were interesting not only for their individual findings but also because they found a divergence in the effectiveness of abatacept between GCA and TAK.

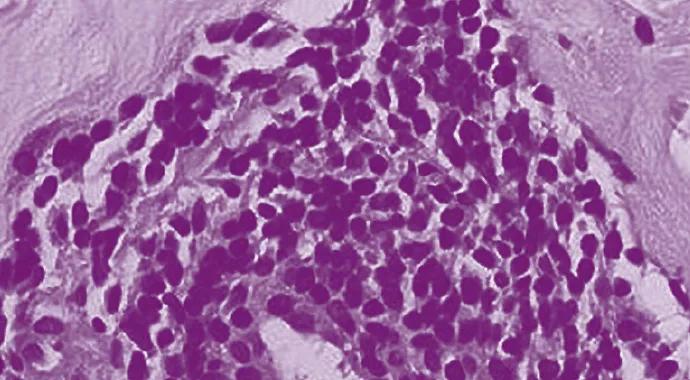

GCA and TAK are two forms of large vessel vasculitis that have unique differences but many similar challenges. GCA is the most common form of vasculitis and occurs in people over the age of 50, most often in their 70s. Since the 1950s, prednisone has been the foundation of treatment for GCA and has been proven to reduce the risk of blindness. However, this has been associated with significant toxicity. In contrast to GCA, TAK is one of the rarest forms of vasculitis affecting about three to nine people per million and predominantly affects young women. Prednisone has again been found to be effective but the side effects have made this an often unacceptable option to patients.

The interest in investigating abatacept in GCA and TAK was based not only on this unmet need to identify treatment options beyond prednisone but also on the safety profile of this medication and its mechanism of action. Abatacept is comprised of the ligand binding domain of CTLA4 plus a modified Fc domain derived from IgG1. As CTLA4 acts as a negative regulator of CD28-mediated T cell costimulation, abatacept inhibits T cell activation. Laboratory evidence suggests that GCA and TAK are antigen-driven diseases, in which T lymphocytes play an important role. By interfering with the T cell activation, abatacept carried the potential to impact a mechanism involved in disease pathogenesis.

Advertisement

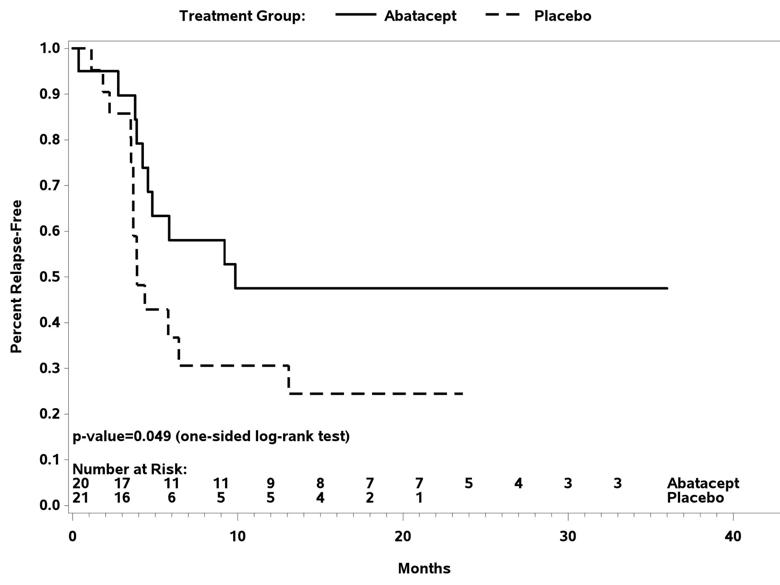

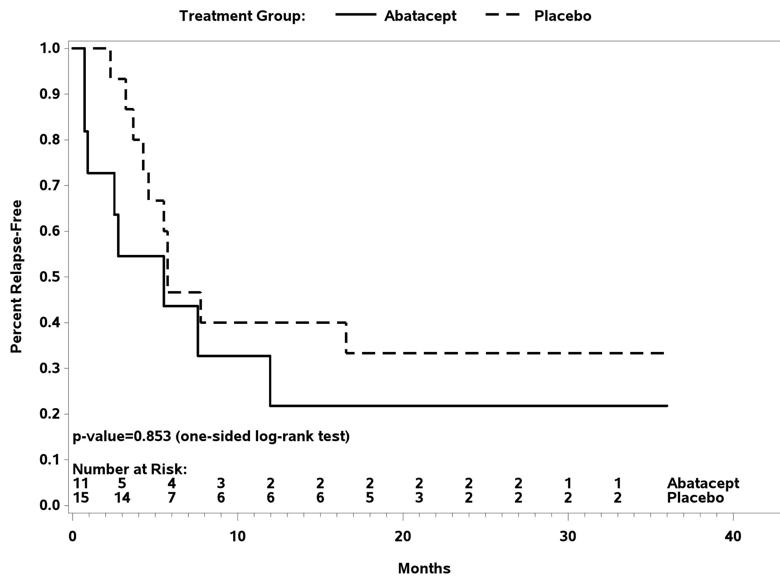

In these trials, patients were initially treated with abatacept and prednisone. At week 12 those in remission underwent a double-blinded randomization to remain on abatacept or be switched to placebo. All patients received a standardized prednisone taper with discontinuation of prednisone at week 28. Patients remained on their blinded treatment assignment until meeting a criteria for early termination or reaching the common close date which was 12 months after randomization of the final patient with that disease. The primary endpoint was remission duration (relapse-free survival).

In the GCA trial, 49 patients received study drug with 41 reaching randomization. The relapse-free survival at 12 months was 48 percent for those receiving abatacept and 31 percent for those receiving placebo (P = 0.049). A longer median duration of remission was seen with abatacept (9.9 months) compared to placebo (3.9 months, P = 0.023). There was no difference in the frequency or severity of adverse events between treatment arms. These results demonstrated that in patients with GCA, the addition of abatacept to prednisone reduced the risk of relapse and was not associated with a higher rate of toxicity compared to prednisone alone.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ba2ab9ed-52db-4a2d-846b-0de63dc02a0f/RheumInset1_jpg)

Figure1. Relapse-free survival following randomization in giant cell arteritis.

In the TAK trial, 34 patients received the study drug with 26 reaching randomization. The relapse-free survival at 12 months was 22 percent for those receiving abatacept and 40 percent for those receiving placebo (P = 0.853). Treatment with abatacept in patients with TAK enrolled in this study was not associated with a longer median duration of remission (abatacept 5.5 months, placebo 5.7 months). There was once again no difference in the frequency or severity of adverse events between treatment arms. Therefore, in patients with TAK enrolled in this trial, the addition of abatacept to prednisone did not reduce the risk of relapse.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/142dc192-65ab-42e3-9dd7-2159bd5c4ed9/RheumInset2_jpg)

Figure 2. Relapse-free survival following randomization in Takayasu arteritis.

Both of these trials provided important advancements to the field.

For GCA, the finding that abatacept combined with prednisone extended the duration of remission beyond treatment with prednisone alone was a significant finding. With the ongoing need to identify additional treatment options in GCA, it is hoped that the results from this trial could lead to a novel therapeutic approach in this disease.

For TAK, although abatacept was not found to provide additional benefit beyond prednisone, the study was significant in being the first randomized trial to be conducted in this disease. By demonstrating that comparative studies in TAK are possible, this work will advance future investigations in TAK.

Another novel aspect of these studies is that these trials were designed to be conducted in parallel by the same investigator team using the same study protocol with the goal of exploring the similarities and differences between these two forms of large-vessel vasculitis. The observation of contrasting results raises intriguing questions about these diseases and highlights the importance of continued research in vasculitis.

* These projects were funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health and Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract HHSN2682007000036C.

Dr. Langford is Director of the Center for Vasculitis Care and Research as well as Vice Chair for Research, Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases. Physicians with questions about these studies, ongoing research in vasculitis at Cleveland Clinic or for referrals should contact Dr. Langford at 216-445-6056 or at langfoc@ccf.org.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being

Nitric oxide plays a key role in vascular physiology

CAR T-cell therapy may offer reason for optimism that those with SLE can experience improvement in quality of life.

Unraveling the TNFA receptor 2/dendritic cell axis