When to consider the possibility of pulmonary artery involvement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/706183d8-cd3e-4cc4-a445-40b040f05cb4/22-RHE-3091666-CQD-650x450-Langford-Takayasu_jpg)

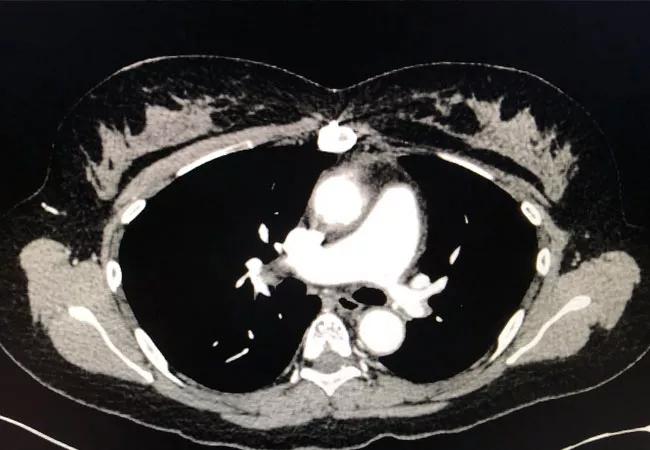

pulmonary artery stenosis

Above: Computed tomography angiography showing stenosis of the left pulmonary artery with vessel wall thickening.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

By Carol Langford, MD, MHS, FACP

CASE PRESENTATION: You receive a call about a 25-year-old female with a three-year history of Takayasu arteritis (TAK) who presents to the emergency room with acute chest pain. Her TAK vascular involvement includes an aneurysm of the aortic root and stenoses of the bilateral subclavian arteries and celiac artery. For this she is receiving treatment with prednisone 5 mg/day and methotrexate 20 mg/week, on which her disease has been in remission. Her only other medications are aspirin 81 mg/day and an oral contraceptive.

She was feeling well until this morning, when she experienced the acute onset of pain in the midline of her lower chest. It had a sharp intermittent quality that did not change with breathing and was not associated with dyspnea. On examination she appeared uncomfortable when the pain was present, but she was not hypoxic.

Evaluation included normal blood counts, chemistries, sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, troponin, ECG and chest radiograph. Her d-dimer was mildly elevated at 820 ng/mL FEU (less than 500 ng/mL FEU being the cutoff to exclude a venous thrombotic event (VTE) in patients with low pre-test probability). As she is allergic to iodine-based contrast, she underwent a venous duplex of the lower extremities, which was negative for deep venous thrombosis, and a ventilation/perfusion scan that showed reduced perfusion of the left lung with perfusion defects in the left upper lobe, lingula and left lower lobe. This was interpreted to suggest high probability of a pulmonary embolism. When you see her, the chest pain has resolved.

Advertisement

An increased frequency of VTE has been observed in a number of different forms of vasculitis. The strongest associations have been VTE in ANCA-associated vasculitis and Behçet’s disease, where both venous and arterial thromboses can occur. For these entities, VTEs are often seen in the setting of active vasculitis. For large vessel vasculitis, the association with VTE is less well established. In giant cell arteritis, database and cohort studies have suggested a greater risk of VTE than for the general population, but the published literature on TAK remains small. Another confounding variable in young women with TAK is the potential use of hormonally based contraceptive methods.

TAK is a primary large vessel granulomatous vasculitis that has an estimated incidence of 150 new cases each year. TAK occurs predominantly in women, with the age of onset between 10 and 40 years old. TAK can affect the aorta, its major branches and the pulmonary arteries, where it manifests as vascular stenoses or aneurysms. The frequency of pulmonary artery involvement in TAK has ranged from 14% to 40% in published series and is likely underappreciated. Pulmonary artery stenoses may not be readily visualized in the computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) examinations performed in TAK to assess large vessel involvement. The pulmonary arteries represent a different vascular bed than the aorta and its branches, such that contrast injection timed specifically for these vessels is required in order for them to be clearly imaged.

Advertisement

While pulmonary artery involvement in TAK often lacks symptoms, it can present with chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, hemoptysis or signs of pulmonary hypertension. In acute settings, pulmonary artery involvement can mimic a pulmonary embolism in both symptoms and imaging findings. Reduced blood flow in perfusion scans can be seen with pulmonary embolism but also with pulmonary artery involvement in TAK. Arteriography, usually with CTA, can support the absence of arterial thrombus as well as other features of TAK, including a thickened arterial wall and tapered narrowing of the vessel.

The possibility that pulmonary artery involvement in TAK was the cause of this patient’s imaging findings was investigated. After receiving premedication prophylaxis, she safely underwent a CTA. This study was negative for pulmonary embolism and showed stenosis and wall thickening of the main left pulmonary artery with reduced blood flow corresponding to the abnormal perfusion scan. Using computerized visualization techniques, it was possible to determine that the pulmonary artery stenosis had been present at the time of the original diagnosis for which she had been treated.

In order to reassess her disease activity status, she underwent an MRA of the aorta and branch vessels, which revealed no new changes. She was maintained on the same treatment for TAK, as she was not felt to have active arteritis. With follow-up, it was determined that her acute chest pain was likely due to esophageal spasm, with the perfusion imaging findings being unrelated to her reason for seeking urgent medical attention.

Advertisement

This patient illustrates that when perfusion imaging suggests a pulmonary embolism in a patient with TAK, further consideration should be given to the possibility of pulmonary artery involvement.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being