In otherwise healthy children, devastating and permanent paralysis can occur

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cba50360-6a81-404e-8b67-02e064be606d/18-ORT-1087_Styron-Hero-Image-650x450pxl_jpg)

18-ORT-1087_Styron-Hero-Image-650x450pxl

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is a recently described rare condition primarily affecting otherwise healthy children. It is characterized by muscle weakness and myelitis of the spinal cord’s anterior horn cells following a viral illness. While it affects the motor function corresponding to the inflamed spinal levels, presentation can be a skip-lesion type pattern, with preservation of function proximal and distal to the affected levels. Sensation remains intact for these children because the myelitis, similar to polio, is limited primarily to the gray matter.

The virus most commonly implicated in AFM, but not always identified, is enterovirus. In the United States, a 2014 outbreak of D68 enterovirus respiratory illnesses was associated with a cluster of AFM cases in Colorado and California. Similarly, in Australia and East Asia, AFM has been associated with outbreaks of enterovirus D71.1

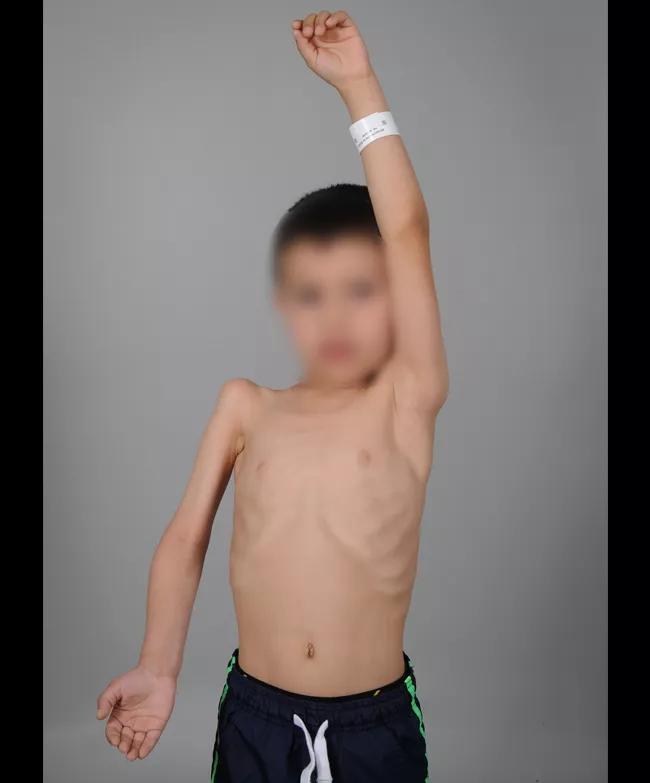

Children with AFM typically present with acute onset of asymmetric flaccid paralysis, often rapidly progressing from normal strength to flaccid weakness with loss of reflexes within hours to a few days. A prodromal illness (typically febrile with respiratory symptoms) a few days prior to the onset of flaccid paralysis is common. Perplexingly, the respiratory symptoms of the prodromal illness are frequently shared by sick contacts within the household, but they are spared any signs or symptoms of AFM. Patients also frequently report pain in the affected limb at the time of weakness onset. There doe not appear to be any ethnic or racial predispositions, pre-existing comorbidities that place these healthy children at increased risk or any association with vaccination status2 (Figures 1 and 2).

Advertisement

AFM differs from more common viral neuropathies such as transverse myelitis and Guillain-Barré. Transverse myelitis has deficits in both motor and sensory function at the affected spinal levels while Guillain-Barré is typically symmetric and ascending in its motor and sensory impairment.

When making the diagnosis of AFM, many tests are frequently ordered, but they rarely help the clinician. Lumbar punctures will frequently demonstrate pleocytosis (74 percent) and some protein elevation (48 percent), but rarely yield an infectious organism.3 Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions of AFM require two criteria:

A lumbar puncture demonstrating pleocytosis can make the diagnosis of AFM probable when in combination with acute-onset limb flaccid weakness, but is not definitive for the condition. 4

AFM, although potentially devastating, is a rare condition. According to the CDC, there were 120 cases between August and December 2014 nationwide. In 2015, there were only 21 cases. Another spike occurred in 2016 with 149 cases. In 2017, the number of confirmed cases dropped to 23.5 If there is a biannual cycle in AFM, another spike is expected in 2018, although it is too soon to say. Reporting suspected cases to the CDC will assist with surveillance and improve our understanding of this devastating condition.

In the acute setting, supportive care is critical. The flaccid paralysis can involve the diaphragm so careful monitoring for respiratory distress is critical.

Advertisement

Many children with AFM will demonstrate some improvement in function, but most will have persistent weakness for months to years. Unfortunately, there are no predictive factors to determine final functional status. Evidence suggests the long-term prognosis for AFM is worse than that for similar conditions such as transverse myelitis.

Nerve transfers may be an effective strategy to restore function in affected extremities when potential nerves are available to transfer. Some patients have experienced a restoration of function in muscles which underwent nerve transfers and persistent weakness in muscles for which no viable transfer options were available.6

Similar to polio, the anterior horn cells are affected in AFM, causing a lower motor neuron deficit. Muscle groups that fail to recover within six months rarely do recover, resulting in residual paralysis. However, some children have continued to improve for two years.1 This creates a quandary for parents and providers. Waiting beyond one year to perform nerve transfers limits their efficacy based on the established paradigm of permanent motor endplate demise following 18 to 24 months of denervation. Therefore, referral to a specialist familiar with AFM and who is capable of performing nerve transfers is recommended within six months to one year of symptom onset.

Timely recognition of AFM and referral to a center familiar with AFM is essential to prevent this disease from becoming a 21st century resurrection of polio.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8cb5a11f-a4fe-4194-8810-fcc7bcda00e2/18-ORT-1087_Styron-Inset-Image-650pxl-width_jpg)

Figures 1 and 2: A child with AFM affecting the proximal muscles in his right upper extremity. Note the muscular atrophy in his supraspinatus fossa, deltoid and biceps. (Photos courtesy of the Shriner’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, where Dr. Styron completed a fellowship in pediatric and congenital upper extremity surgery.)

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cba50360-6a81-404e-8b67-02e064be606d/18-ORT-1087_Styron-Hero-Image-650x450pxl_jpg)

References:

Advertisement

Advertisement

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient