Program's approach maximizes donor safety without compromising recipients' outcomes

Boundary-pushing surgical techniques have enabled Cleveland Clinic’s living donor liver transplant (LDLT) program to regularly and successfully use small-size donor grafts — especially left lobe grafts accounting for 30-40% of total liver volume — that maximize donor safety without compromising graft functionality in the recipient.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The surgical techniques involve modulating the implanted graft’s inflow and augmenting its outflow to reduce the potential for dysfunction and small-for-size syndrome (SFSS).

Even with aggressive use of small grafts, the transplant surgeons report in a recent seminal study that they achieved high graft and patient survival rates at one, three and five years, with no outcome differences between left- and right-lobe grafts and low incidence of SFSS.

Nearly half of all LDLTs performed at Cleveland Clinic since 2012 have involved left lobe grafts. Wider adoption of Cleveland Clinic’s approach by other U.S. transplant centers could encourage more people to volunteer as living donors and increase the supply of grafts available for transplant.

“Our team’s results show that left lobe and small graft transplants can work with some modification of technique, which is feasible for every transplant surgeon in the United States,” says Cleveland Clinic liver transplant surgeon Masato Fujiki, MD, the report’s lead author. “Not every donor candidate can donate the right lobe, and many potential donors are hesitant to have the majority of their liver removed. If all programs started using small grafts, we could expand the pool of living donors and perform more lifesaving transplants.”

Living donor liver transplants have been in use since 1989, when surgeons in Australia replaced a 17-month-old baby’s diseased liver with a left-lobe graft donated by his mother. Adult-to-adult LDLT began in Japan in 1994 utilizing the left lobe, but emphasis quickly shifted to right-lobe transplants due to concerns about SFSS resulting from undersized left-lobe grafts.

Advertisement

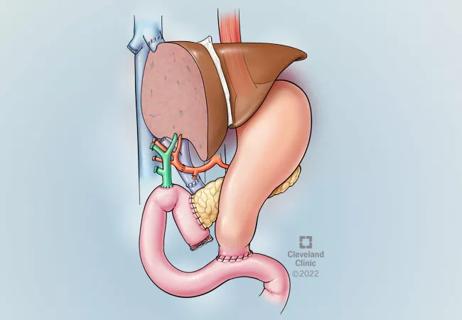

LDLTs have significant potential to reduce the global shortage of available organs. But the complex procedure requires precisely balancing risks to the participants: specifically, obtaining a graft small enough to preclude undue harm to the donor while large enough to function adequately in the recipient.

LDLTs utilizing small grafts, particularly left-lobe grafts, are safer for donors but can cause complications for recipients and contribute to graft dysfunction, failure and potential mortality if the liver mass is insufficient to sustain metabolic demands.

LDLTs have proliferated in Asia, where there is a critical shortage of cadaveric donor grafts. Asian transplant surgeons have developed techniques to modulate graft inflow — often utilizing splenectomy — and augment outflow.

But LDLT has not gained traction in Western countries, likely due in part to lingering fears of SFSS and a reluctance to perform splenectomy in the recipient, with its attendant risks of surgical, thrombotic, hemorrhagic and infection-related complications. Fewer than 5% of liver transplants in the United States involve living donors; of those U.S. adult-to-adult LDLTs, only 5% utilize the left lobe, even though it tends to be safer for the donor.

Cleveland Clinic is one of only a few Western transplant centers to report consistently excellent outcomes after adult LDLT using small-size grafts.

SFSS, stemming from excessive portal vein flow relative to graft volume, is a critical, life-threatening complication of LDLT.

Advertisement

Predicting the amount of portal hypertension and resultant blood flow into and out of the graft in LDLT is crucial for success, especially when using small-size grafts. Inadequate portal flow will prevent graft regeneration; excessive flow leads to graft injury and SFSS. The optimal range of portal vein flow to stimulate regeneration while avoiding SFSS is unknown.

SFSS can occur in as much as 20% of patients post-transplant, according to previous series. In general, the condition involves a graft smaller than the weight or volume of liver needed to meet a patient’s metabolic demands. It is characterized by cholestasis, intractable ascites and sepsis, leading to high mortality rates.

Studies have quantified the threshold of SFSS as a graft-to-recipient weight-ratio (GRWR) of <0.8%, with graft volume versus standard liver volume (GV/SLV) ratios of <40% associated with poor graft survival, reduced survival and prolonged recovery. Typically in LDLT, GRWRs of 0.8% or GV/SLVs of at least 30% are recommended to optimize patient survival rates.

The pathophysiology of SFSS includes sinusoidal endothelial cell injury, focal hemorrhage, inflammation, impaired hepatic microcirculation, hepatocyte necrosis and liver failure. These likely result from multiple factors involving both graft and recipient, primarily increased portal vein flow (PVF) and pressure that causes shear stress injuries and impairs liver regeneration, as well as the hepatic artery buffer response, which affects hepatic arterial flow and vascularization of the biliary tree.

Advertisement

There is no definitive treatment for SFSS. The basic strategy involves providing supportive care and waiting to determine if the graft regenerates. Retransplantation, if feasible, may be needed.

Asian transplant centers have used various intraoperative measures in an effort to reduce PVF, avoid graft hyperperfusion and overcome SFSS when utilizing small-size grafts. They include splenectomy; splenic artery ligation and embolization; and diversion of portal vein blood by hemi-portocaval, mesocaval and splenorenal shunts.

After observing those techniques, and with the encouragement of Charles Miller, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s Enterprise Transplant Director, Dr. Fujiki and his colleagues began adopting and adapting some of them more than a decade ago to shift the LDLT program’s focus to smaller, primarily left-lobe, grafts. Their motivation was to create the safest possible conditions for donors.

“This is very important because living donor transplantation is a unique situation in which we are essentially violating the no-harm policy for the donor in order to save the recipient’s life,” Dr. Fujiki says. “Donor safety improves if we can use smaller grafts, but this can make it difficult for the recipient to have a good outcome.”

The small-graft LDLT surgical techniques used at Cleveland Clinic are:

Advertisement

Graft selection is based on GRWR, the recipient’s model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score and severity of portal hypertension, and the donor’s anatomy. Cleveland Clinic’s LDLT program prefers to use left-lobe grafts with GRWR ≥0.6%. If using the left lobe isn’t feasible, a right-lobe graft with GRWR ≥0.6% and a future remnant volume ≥30% is acceptable.

An important consideration when performing splenectomy to modulate small graft inflow is whether to undertake the procedure before or after graft reperfusion. Post-reperfusion splenectomy may cause initial graft insult due to excessive portal flow. However, splenectomy before graft implantation and reperfusion is more difficult technically and may result in increased blood loss.

Dr. Fujiki and his colleagues have found that pre-reperfusion splenectomy, if it can be done safely, may be appropriate when dealing with marginal, fragile grafts — those that are especially small and/or from an older donor. They advocate pre-reperfusion splenectomy when grafts are at high risk of SFSS.

The surgeons typically perform pre-reperfusion splenectomy when the recipient has one or more of these indications: estimated GRWR ≤0.7%, preoperative hepatic venous pressure gradient ≥16 mmHg, and MELD score ≥20. Additional risk factors that may contribute to the need for pre-reperfusion splenectomy are donor age ≥45 years, the presence of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, and spleen volume ≥1,000 mL.

Indications for post-reperfusion splenectomy include portal venous flow ≥250 mL/100 gLW, portal venous pressure ≥20 mmHg, and/or portal pressure gradient ≥10 mmHg after graft implantation. Transplant recipients with poor hepatic artery flow due to portal hyperperfusion also are candidates for post-reperfusion splenectomy.

To mitigate the risk of infection following splenectomy, all LDLT recipients at Cleveland Clinic undergo preoperative vaccination for pneumococcus, meningococcus and haemophilus influenzae type B. Recipients also receive low molecular-weight heparin after the splenectomy to reduce thrombotic risk.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b80dd974-6c08-4470-80ad-388755affbb7/22-DDI-3110663-Image-1-650x450-1_jpg)

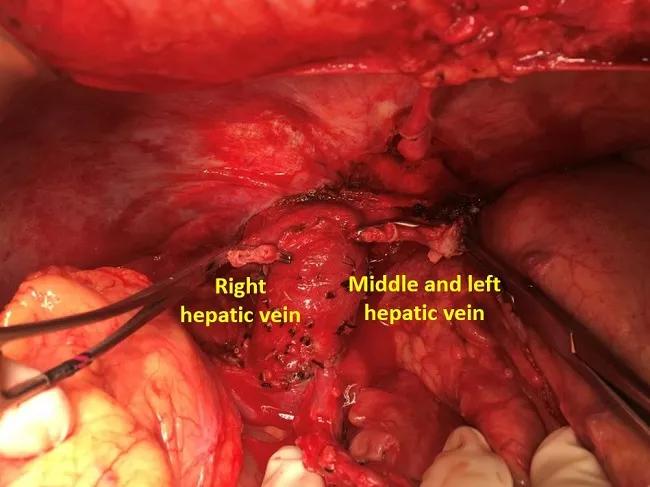

Separated hepatic veins in preparation for creating the venous cuff, which will augment graft outflow.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a9b29783-b614-4c59-8fdd-fb34f7be0226/22-DDI-3110663-Image-2-650x450-1_jpg)

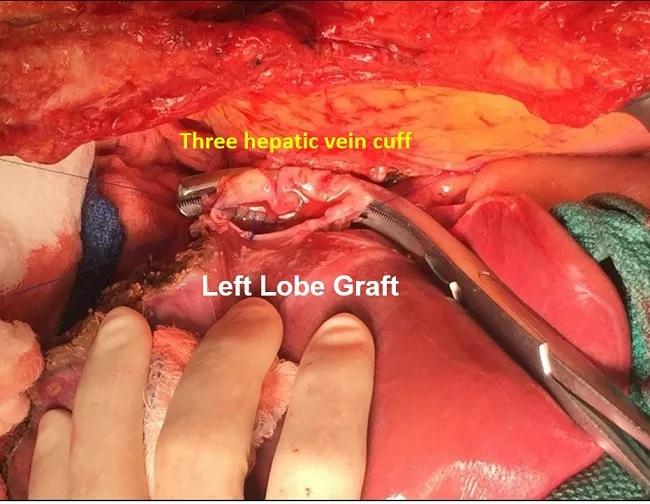

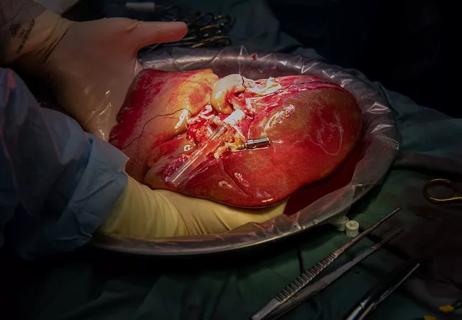

The completed three-vein venous cuff is anastomosed to a venoplastied hepatic vein of the left-lobe graft

To optimize venous outflow in left-lobe grafts, the Cleveland Clinic surgeons routinely connect the recipient’s right, middle and left hepatic veins to form a large venous cuff, providing a wider diameter than the individual veins. The cuff is anastomosed to a venoplastied hepatic vein of the left lobe graft.

The three-vein technique was adapted from Cleveland Clinic’s whole-liver transplant program, where it is regularly used. This outflow maximization approach is simpler than vein-patching techniques used in some Asian transplant centers and reduces outflow complications and ascites production.

In right-lobe grafts, outflow is augmented by first making a downward incision on the right hepatic vein into the liver parenchyma at the caudal end, then applying a more than half-circumferential venous patch plasty around the incision. For implantation, a side clamp is applied to the vena cava, a downward incision is made in the recipient’s right hepatic vein into the cava, and the orifice is widened.

To evaluate the impact of surgical modifications on small-size graft LDLT outcomes, Dr. Fujiki and his colleagues examined 130 adult LDLTs they performed between 2012 and 2020. Median GRWR was 0.85%. Sixty-one transplants (47%) utilized left-lobe grafts. Seventy-two (56%) involved splenectomy for inflow modulation, either before (n=50) or after (n=22) graft reperfusion. Compared with right-lobe graft recipients, left-lobe recipients had significantly lower GRWR (0.78% vs. 0.91%) and underwent splenectomy more often.

Graft survival rates were 94% at one year, 90% at three years and 83% at five years. The rates did not differ between left- and right-lobe grafts, or between patients who underwent splenectomy vs. those who did not.

In the 72 cases where splenectomy was performed, measurement of post-reperfusion portal flow showed that splenectomy significantly reduced flow without increasing complication rates. For left-lobe graft LDLTs, patients who underwent pre-reperfusion splenectomy had better one-year graft survival than those who underwent splenectomy after reperfusion. The incidence of portal vein thrombosis and the severity of Clavien’s grade complication was similar in patients with and without splenectomy. The overall postoperative hemorrhage rate in patients who underwent splenectomy was 5.3%. Pre-LDLT vaccination successfully prevented overwhelming sepsis.

Cleveland Clinic’s study is the largest series of simultaneous splenectomy/LDLT outcomes to have been reported in a Western transplant center.

Informed by the study’s results, Dr. Fujiki and his colleagues have created an algorithm that expresses the decision-making process they follow for splenectomy use and timing.

Although the use of small-size grafts predominated during the study period, SFSS occurred in only one patient (0.8%) and early allograft dysfunction (EAD) developed in only 18 patients (13.8%). Multivariable logistic regression showed that the recipient’s MELD score and the use of a left-lobe graft were independent risk factors for EAD. Splenectomy was a protective factor.

During the study, 12 patients received grafts smaller than the recommended minimal GRWR requirement of 0.6%. One-, three- and five-year graft survival were 92%. One patient experienced graft loss associated with a bile leak and died. A second patient experienced EAD which resolved. With a median follow-up of 40 months after LDLT, the 11 surviving recipients of very small grafts were doing well.

Overall, the study results show that liberal use of splenectomy combined with three-vein outflow augmentation in LDLT can minimize the risk of SFSS, even with very small grafts. “These modifications make it possible to have good outcomes for both recipients and donors,” Dr. Fujiki says.

Currently, 49% of LDLTs performed at Cleveland Clinic utilize left-lobe grafts, Dr. Fujiki says — a slight increase from the 47% reported in the study.

In addition, since the arrival of transplant surgeon Choon Hyuck David Kwon, MD, in 2018 as Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Laparoscopic Liver Surgery Program, 100% of donor hepatectomies in LDLT have been performed laparoscopically.

Together, the use of small grafts retrieved with minimally invasive techniques enhances donor safety and recovery.

“This is a significant change and a powerful combination,” Dr. Fujiki says. “Few transplant centers in the world are performing laparoscopic hepatectomy using left-lobe grafts. With our capabilities, this is something that we at Cleveland Clinic can do.”

“Our successes in LDLT happen for a good reason,” he says. “At Cleveland Clinic, we have a willingness to innovate, an openness to new things, and the teamwork that makes it possible to reach ambitious goals and achieve better outcomes for our patients.”

Advertisement

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Minimally invasive approach, peri- and postoperative protocols reduce risk and recovery time for these rare, magnanimous two-time donors

Patient receives liver transplant and a new lease on life

New research shows dramatic reduction in waitlist times with new technology

Cleveland Clinic study shows positive outcomes for donors and recipients

Program expands as data continues to show improved outcomes

Atypical cells discovered after primary sclerosing cholangitis diagnosis

Research examines risk factors for mortality