Minimally invasive approach, peri- and postoperative protocols reduce risk and recovery time for these rare, magnanimous two-time donors

They’re known in the medical literature as extreme living donors — people who have given two solid organs, either simultaneously or sequentially, to a transplant recipient or recipients.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

That’s the technical term. Transplant surgeon C. H. David Kwon, MD, PhD, offers a more lyrical description.

“I call them people with a golden heart,” says Dr. Kwon, Cleveland Clinic’s Director of Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery. “They have a different attitude toward life and toward giving. They feel really happy to have helped someone. The action of giving gives back to the person who gives.”

Dual-organ living donation — usually involving a kidney and a liver segment or a kidney and distal pancreas — increases the availability of a scarce resource, reducing wait times for transplant recipients (often pediatric patients) and potentially saving more lives.

But dual-organ donation remains exceptionally rare, due to the small number of people willing to undergo the demanding procurement procedure twice and transplant programs’ mandate to minimize donor risks.

A 2022 study using national transplant data identified 146 dual-organ living donors in the United States since 1994 — less than one-tenth of one percent of all transplants involving living donors during those 18 years.

Cleveland Clinic’s extensive experience in transplantation and expertise in minimally invasive surgery, which reduces donors’ postoperative pain and expedites recovery, facilitates dual-organ living donation. Since 2012, 22 dual-organ living donors have had one or both of their procurement surgeries at Cleveland Clinic.

“We have one of the largest series in the U.S. that I know of,” Dr. Kwon says. “Altruistic donors come to us because we do minimally invasive surgery and because of our surgical expertise in utilizing the [smaller] left lobe of the liver.”

Advertisement

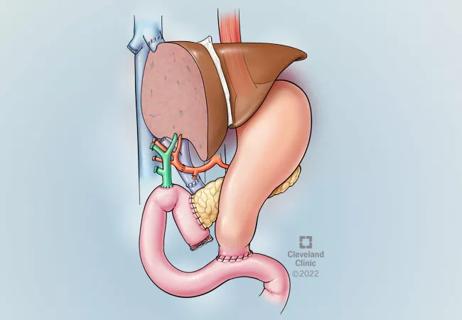

Left-lobe hemihepatectomy is safer for donors because it preserves a larger functional remnant but requires vigilant postoperative management of recipients due to the smaller graft size.

Cleveland Clinic has provided fully laparoscopic living donor hemihepatectomy for transplantation since 2019 with the arrival of Dr. Kwon, one of the world’s most experienced laparoscopic living donor liver surgeons. The living donor liver transplant program under the direction of Koji Hashimoto, MD, PhD, has developed and demonstrated the efficacy of surgical modifications that lower the threshold for using small grafts, especially left-lobe grafts, without compromising organ functionality or transplant outcomes.

“Cleveland Clinic has been pioneering in this field, particularly in the minimally invasive approach for living donor surgery,” says pediatric gastroenterologist and hepatologist Kadakkal Radhakrishnan, MD. “That’s an area that needs expertise.”

“We have observed, especially after we started our laparoscopic living donor program, that previous altruistic kidney donors want to donate a portion of their liver now,” Dr. Kwon says. “And previous liver donors want to donate a kidney. It goes both ways.”

Most transplant programs’ reluctance to allow dual procurement from a living donor stems from the perceived risk of morbidity and mortality, and from the ethical obligation to prevent undue harm to a healthy volunteer arising from an elective procedure.

Due to the rarity of dual-organ living donation, there are few published case and series reports, and no consensus guidelines exist on when the procedure is appropriate. While mortality and the incidence and severity of morbidity appear low, the case volume is insufficient to draw statistically meaningful conclusions. Likewise, extended follow-up data on dual-organ living donors is limited and there are no studies evaluating the long-term health consequences of donating more than one organ.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic’s transplant program has determined that dual-organ living donation is acceptable on a case-by-case basis after extensive medical and psychological evaluation of the donor. To reduce donor risk, partial liver donation is restricted to the left lobe, which constitutes roughly 30% of the organ.

“The majority of transplant centers around the world use the right lobe,” Dr. Kwon says. “Because you're transplanting a bigger portion of the liver, it's easier in the management of the recipient, even though it's putting more burden on the donor.”

When resecting the living donor’s liver, Dr. Kwon typically shifts the resection plane approximately 1 centimeter rightward from its usual position. The shift enables retrieval of a viable portion of the caudate as well as 3-5% more of the liver’s volume.

“That one centimeter is actually easier to achieve when you do it laparoscopically,” Dr. Kwon says. “And by doing what I'm doing, I'm adding probably 10% or more function in the left lobe graft. That, plus the techniques Dr. Hashimoto uses, allows the smaller graft to adapt well to the recipient.”

Those surgical techniques involve modulating the implanted graft’s inflow by splenectomy and augmenting its outflow by utilizing all three recipient hepatic veins. This reduces the potential for graft dysfunction and small-for-size syndrome.

In addition to reducing the risk of dual-organ living donation, left lobe graft utilization increases organ availability for pediatric and small-sized adult recipients. Those patients can’t accommodate larger donor grafts and may have lower liver disease severity scores than other transplant candidates, resulting in extended wait times.

Advertisement

Left lobes from dual-organ living donors is “a wonderful combination to fill a niche that has not been taken care of in the past,” Dr. Kwon says.

Other Cleveland Clinic approaches to safeguard dual-organ living donors involve modifying the anesthesia regimen and postoperative pain management.

Historically, low central venous pressure (CVP) techniques such as preoperative fluid restriction, vasodilators and diuretics have been used to decrease potential blood loss in patients undergoing liver surgery. “We dry up the patient as much as possible, because if fluid volume is high, there is more bleeding when you cut the liver,” Dr. Kwon says.

However, fluid restriction could cause renal stress in a previous kidney donor, so Cleveland Clinic anesthesiologists limit CVP reduction to protect the remaining kidney in dual-organ living donors.

Likewise, to ensure renal protection in dual-organ living donors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not used after surgery, Dr. Kwon says. Instead, the minimally invasive approach, along with transabdominal plane blocks and medications such as gabapentin and acetaminophen, makes it possible for patients to recover without much pain.

A recent dual-organ living donation illustrates the procedure’s impact and donors’ magnanimity.

In 2020, the Rev. Dr. Nathan Howe, then 37 and a United Methodist Church pastor, donated a kidney to his 74-year-old father, John. The elder Howe had polycystic kidney disease and had undergone 2 ½ years of peritoneal dialysis while awaiting a transplant.

Advertisement

John Howe initially resisted receiving a kidney from a living donor because of the risk he thought the person would face. A seminar on living donation by Cleveland Clinic in collaboration with the National Kidney Foundation changed his mind.

Nathan Howe underwent donor evaluation and was found to be a match for his father. His kidney was retrieved laparoscopically and implanted by Cleveland Clinic's renal transplant surgical team. Father and son spent just two nights in the hospital.

That positive experience and Nathan Howe’s realization that a second living donation was possible motivated him to act. “I think it’s important that we support one another in whatever ways we can,” he says. “This is a way I was able to do so.”

Howe contacted Cleveland Clinic in 2024 to determine if he could safely donate a portion of his liver. Evaluation confirmed his eligibility. Eventually he was matched with 11-year-old Ahmad Rai, who was born with the genetic disorder progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) type 2. The condition causes bile acids to aggregate within hepatocytes, overloading the hepatocellular system and resulting in structural damage, dysfunction and eventual failure of the liver.

Ahmad had undergone a living-donor liver transplant at Cleveland Clinic at age 4 in 2016. He developed bile duct complications several years later, which caused recurrent hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, portal hypertension and splenomegaly. The insertion of biliary drains and intrabiliary radiofrequency ablation did not resolve the bile duct obstruction.

“Ahmad’s liver was not improving and started failing again. It was ultimately decided he would need a second liver transplant,” says Dr. Radhakrishnan.

“Although Ahmad was very sick, his PELD [pediatric end-stage liver disease] score wasn't really high, so he didn't have much priority on the transplant waiting list,” Dr. Hashimoto says. “But doing the transplant in a timely fashion is very important, particularly for children. They have to grow. They have to go to school. Fortunately for Ahmad, there was a perfect living donor who was a good match.”

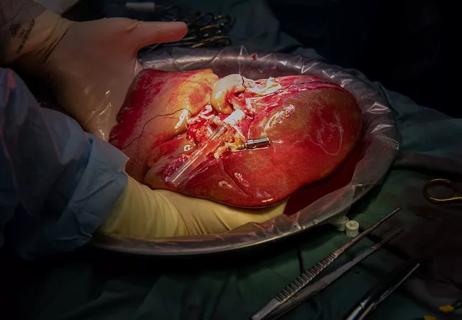

Dr. Kwon led the laparoscopic retrieval of Nathan Howe’s left lobe and Dr. Hashimoto performed the transplant.

Cholecystectomy, clipping and dissection of the hepatic vessels, and transection of the liver parenchyma were carried out through five abdominal ports. A 9-centimeter suprapubic transverse skin incision over the previous Pfannenstiel incision used for Howe’s kidney donation surgery allowed removal of the liver graft and gallbladder. The abdominal wall incision was made horizontally to reduce the potential for hernia.

Dr. Kwon recovered 31% of Howe’s liver. Because of Ahmad’s small size — he weighed 70 pounds at the time of surgery — there was no need to include a portion of the caudate in the donor graft or to modify inflow and outflow, since small-for-size syndrome would not be a concern.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b0381bf7-8fd1-4c1f-ba77-315c8711db17/Liver-transplant-11yearold)

Ahmad Rai and his mother, Aya Akkad

Donor and recipient recovered uneventfully. Howe was discharged after five days. Ahmad’s liver is functioning normally. He is back in school and enjoys playing soccer and video games.

“He has a good chance to live a normal life,” Dr. Hashimoto says.

Although Howe’s liver donation was made anonymously, Ahmad and his family were able to meet Nathan postoperatively by working with their transplant coordinator. Ahmad and Howe talked about Ahmad’s love for soccer, the paths that led to donation and transplant, and the sense of gratitude and hope each has, thanks to the other.

“I’m very grateful to [his first liver donor] and Nathan,” Ahmad says. “I wouldn't be where I’m at today without them.”

“Organ donation is incredibly life-giving for both donors and recipients,” Howe says. “It's important to nurture those connections.”

Advertisement

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Patient receives liver transplant and a new lease on life

New research shows dramatic reduction in waitlist times with new technology

Cleveland Clinic study shows positive outcomes for donors and recipients

Program's approach maximizes donor safety without compromising recipients' outcomes

Program expands as data continues to show improved outcomes

Atypical cells discovered after primary sclerosing cholangitis diagnosis

Research examines risk factors for mortality