The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

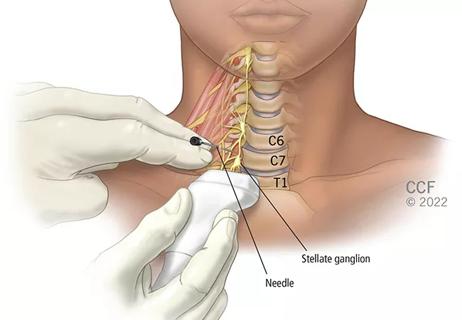

Study sheds light on how clinicians addressed their patients’ pain and insomnia during the pandemic

Patients report improved sense of smell and taste

Clinicians who are accustomed to uncertainty can do well by patients

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Unique skin changes can occur after infection or vaccine

Cleveland Clinic analysis suggests that obtaining care for the virus might reveal a previously undiagnosed condition

As the pandemic evolves, rheumatologists must continue to be mindful of most vulnerable patients

Early results suggest positive outcomes from COVID-19 PrEP treatment

Could the virus have caused the condition or triggered previously undiagnosed disease?

A Q&A with infectious disease expert Eric Cober, MD

Advertisement

Advertisement