First full characterization of kidney microbiome unlocks potential to prevent kidney stones

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a3fd12ef-c6a0-409c-8dc8-259eb7eeb8be/kidney_microbiome_microscopy)

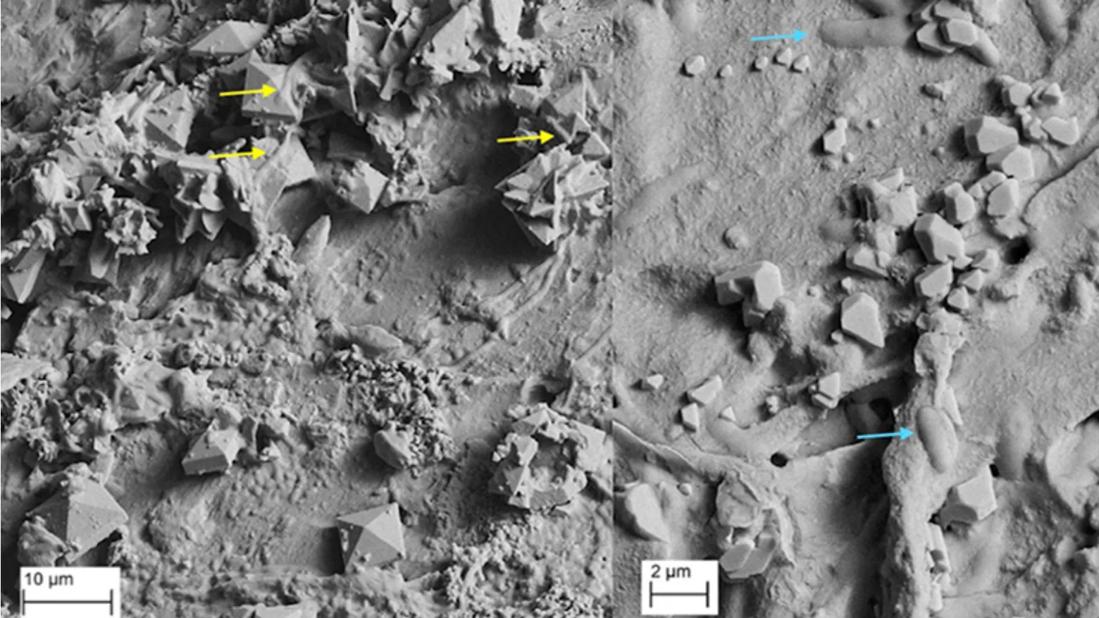

microscopy image of kidney stones

Scanning electron microscopy shows direct interaction of kidney-resident E. coli (left; yellow arrows) on typical crystal structures of calcium oxalate (CaOx) dihydrate crystals the bacteria made, which resemble kidney stones. On right, rod shaped Lactobacillus crispatus do not interact with crystals, and the few crystals generated do not resemble kidney stones.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research.

Cleveland Clinic researchers have found definitive proof of a kidney microbiome that influences renal health and kidney stone formation, demonstrating that the urinary tract is not sterile and low levels of bacteria are normal.

The Nature Communications publication describes the rigorous multi-pronged approach a team led by Aaron Miller, PhD, and José Agudelo, MD, used to identify and characterize the small bacterial community by combining preclinical, human and dish studies. They also identified certain bacteria within the microbiome that could promote or block kidney stone development and showed that antibiotic misuse (commonly associated with kidney stone development in a hospital setting) skewed the microbiome towards stone-promoting bacteria.

Dr. Miller hopes his team’s findings will help overturn the concept of a sterile urinary tract once and for all and lead to better prevention or treatment options for a condition that hasn’t seen major medical advances in over three decades.

“Urologic diseases like kidney stones impact 63% of the adult population and are getting worse,” he says.“The data consistently points towards bacteria. If we can’t get over the assumption of sterility, we can’t develop more effective treatments and preventative options.”

Normal bacteria levels in urine are very low, but they are rarely zero. Despite this, the urobiome – microbiome of different organs in the urinary tract including the bladder and kidneys – has been a controversial topic since its discovery in human urine less than 15 years ago.

Advertisement

First author and urologist José Agudelo, MD, had personally seen bacteria in the kidneys of his patients in the decade he spent treating patients in Venezuela. However, he explains that these observations and previous studies of a kidney microbiome gave compelling evidence but left enough room for doubt.

First author and urologist José Agudelo, MD, who has extensive experience in urinary stone disease, explains that previous indirect findings of a kidney microbiome gave compelling evidence but left room for doubt.

Bacterial communities need to meet three criteria to be considered a true microbiome: stability, consistency and reproducibility and being metabolically active. The team’s methods demonstrated each of these aspects for bacteria found in the urinary tract. Their research also showed that bacteria living in the urinary tract were not only there because of disease, since they found them in the urinary tract of people without evidence of urologic disease.

Other studies had shown that two species Drs. Miller and Agudelo had identified, E. coli and Lactobacillus crispatus, had been associated with the presence and absence of kidney stones, respectively. The researchers asked if the metabolic activity of their newly discovered microbial community played a role in kidney stone formation.

To see whether the kidney microbiome could influence stone formation, the researchers grew bacteria using a special chamber that mimics the movement of urine in our kidneys. They then added the “raw ingredients” of kidney stones, oxalate and calcium, to see what happened.

Advertisement

Several large, stone-like crystal structures formed in chambers growing E. coli. Chemical and X-ray analyses revealed these structures were indistinguishable from human kidney stones. No stones formed in the chambers growing Lactobacillus in this way. Growing the two bacteria together resulted in very small crystal structures that were structurally and chemically different from kidney stones, indicating that Lactobacillus somehow blocks E. coli’s ability to form kidney stones.

In preclinical models, the team also saw that antibiotic overuse shifted the balance of the kidney microbiome away from the healthy Lactobacillus towards the stone-forming E. coli. They believe their findings, taken together, may explain why individuals on long-term antibiotic courses are more prone to developing kidney stones.

“Antibiotics are one of – if not the – most miraculous inventions of the modern age, but they do not come without consequences,” Dr. MIller says. “Our findings about how antibiotics impact the renal microbiome and stone formation give us a critical piece of the puzzle we need to combat these consequences.”

Dr. Agudelo says his team’s findings suggest that different bacteria produce pro- and anti- kidney stone molecules, which he wants to use in new therapeutic and diagnostic techniques. He is already working to understand which bacterial metabolites influence stone formation, and how.

“If the kidney microbiome can influence kidney stones, it can likely influence other kidney diseases as well,” Dr. Miller adds. “We are already looking at microbial signatures for other kidney diseases and have even submitted a grant to investigate how certain genetic variants influence the renal microbiome and kidney disease risk in different ethnicities.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

First single-port renal vein transposition reduces recovery time and improves outcomes

Findings confirm microbial variability, offer new potential treatment strategy

Research program sets the stage for clinical trials

Findings could help identify patients at risk for poor outcomes

Findings show greater reduction in CKD progression, kidney failure than GLP-1RAs

Metabolites from animal product substrates implicated in heart failure development in community cohorts

Pairing machine learning with multi-omics revealed potential therapeutic targets