Team uses surgical loop and forceps to remove tapeworm from subretinal space

By Sunil K. Srivastava, MD; Arthi G. Venkat, MD; and Kimberly Baynes, MSN, RN

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 68-year-old woman with a history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was admitted to an outside hospital with fever and abdominal pain. Imaging showed pulmonary and hepatic lesions, and further workup indicated an unspecified infectious disease.

After treatment with antibacterial and antifungal medications, the patient came to Cleveland Clinic for a second opinion. Due to reported vision changes, the patient was seen at Cole Eye Institute as part of her workup.

The patient’s visual acuity was 20/50 (OD), 20/30 (OS). Her anterior chamber and vitreous were quiet, without signs of inflammation. Dilated fundus examination revealed bilateral multifocal yellowish oval subretinal/choroidal lesions with some elevation.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/95276691-b449-4666-83ad-c75d7f35234b/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Slide-5_jpg)

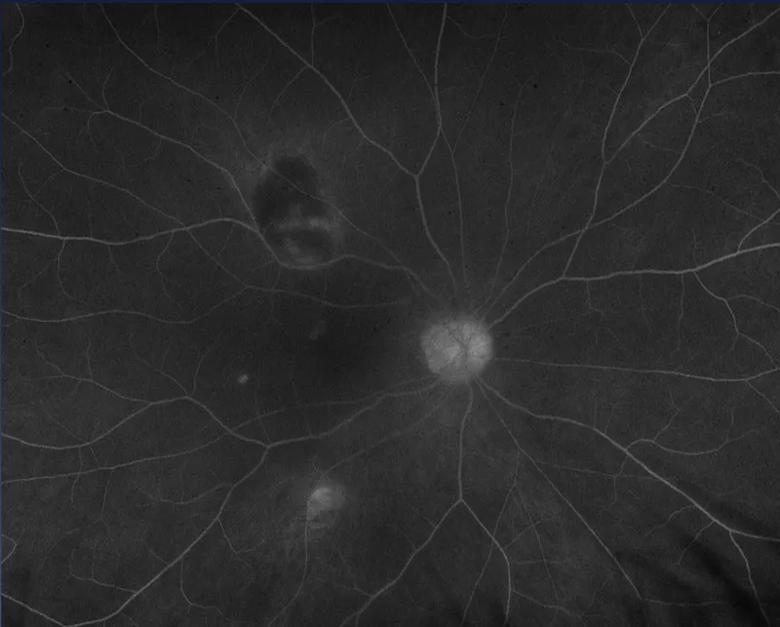

Fluorescein angiography showed central blocking with mild leakage around the edge of the lesions.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/39c3b461-7453-4fd5-912e-313c9efe9aad/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Slide-6_jpg)

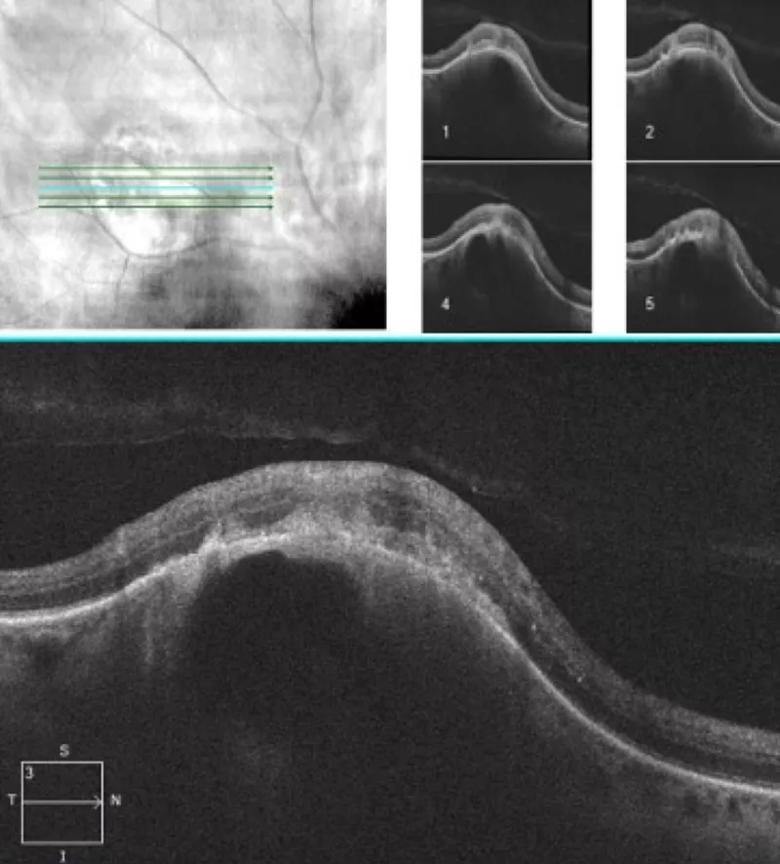

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed a cyst-like structure within the choroid, displacing the retina anteriorly.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c48070d6-475d-4644-a08e-ac22a96f2fb6/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Slide-7_jpg)

At this point, we diagnosed bilateral multifocal choroiditis. The exact etiology was not clear, but we believed further workup, including brain imaging, laboratory testing and blood cultures, was required. We opted to wait for those results and defer a biopsy to determine etiology of the ocular lesions.

Multiple small cystic lesions were detected on brain MRI and suspected to be neurocysticercosis, a parasitic disease. That finding led to a liver biopsy, which definitively detected the presence of a cestode (tapeworm), eventually identified as Versteria.

Versteria infection has previously been reported in animals, including mustelids. The only report in a human involved a kidney transplant recipient in Canada.

Advertisement

How the patient in this case contracted Versteria is unknown.

Tapeworm larvae are assumed to be ingested through a food source or water. Larval infections become invasive when they migrate from the intestines to other tissues and organs through the bloodstream. Because of heavy blood flow to the retina and choroid, ocular cysticercosis is possible.

The consequences of ocular cysticercosis are dependent on the location of the parasite. Damage to the retina occurs in the areas of invasion with minimal intraocular inflammation. However, if the parasite invades the vitreous, a severe intraocular inflammatory reaction occurs, potentially with severe vision complications.

The patient was started on a several-month course of antiparasitic medications albendazole and praziquantel.

Over six months, the infection seemed to resolve. The patient’s fever and abdominal pain abated. Lesions in her brain, lung and liver improved. Her choroidal lesions seemed to become pigmented and appear flatter.

At month 7, however, the patient reported changes in her right eye. There was new intraretinal hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and the appearance of a new lesion.

While infectious disease specialists confirmed that the patient had been improving systemically, we were concerned that this lesion could represent a new change — either a new inflammatory lesion, a secondary choroidal neovascular membrane or a new focus of infection.

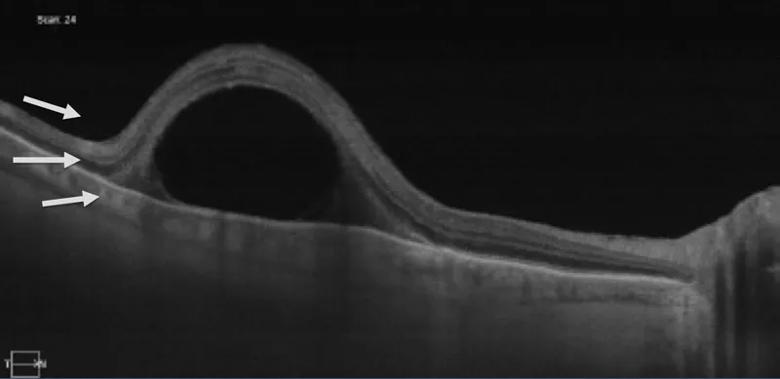

OCT revealed that the original choroidal lesion now appeared to have moved into the subretinal space. We suspected that the parasite was present, still alive and working its way out. To determine the cause and prevent intensifying inflammation, we proceeded with surgery to remove the parasite.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2f960763-a543-4d7b-9e67-6b1d4cdbef01/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Slide-12_jpg)

A lesion initially under the retinal pigment epithelium is now above it.

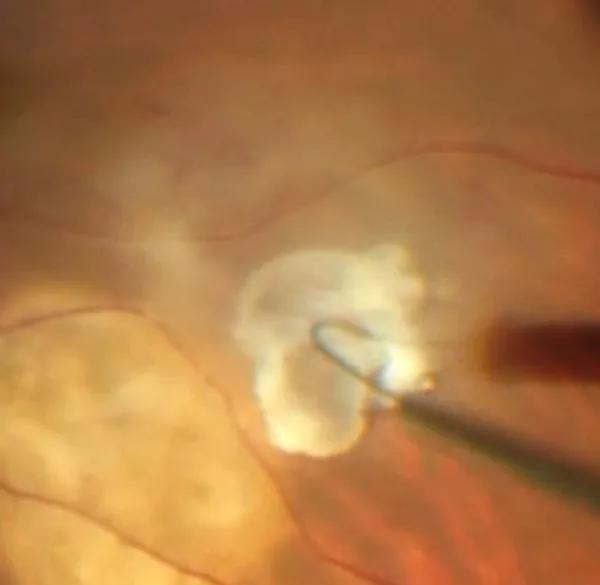

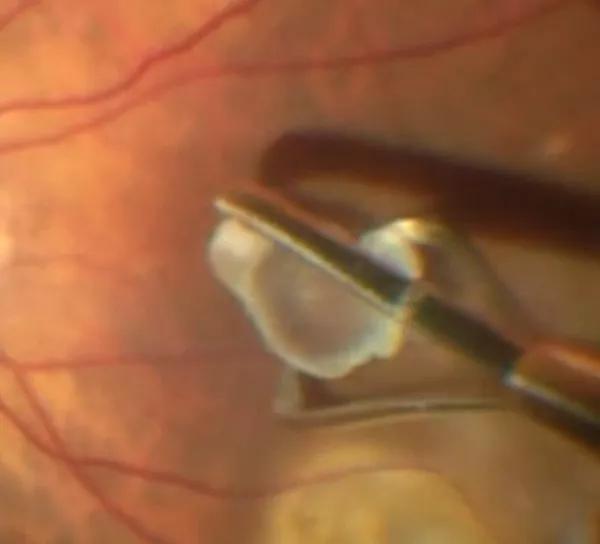

During surgery, we could see worsening of inflammation in the vitreous, indicating the lesion had begun to exit the retina and invade the vitreous. We created a small hole in the retina, and through this hole we used a flexible surgical loop to nudge the parasite out of the subretinal space and into the vitreous.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6c8a023d-e910-466e-bdb9-ea5c1bd60141/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Flexible-loop-Inset_jpg)

We then carefully grabbed the parasite with forceps and removed it from the eye.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/123888ef-ec7d-48d7-87c2-46b29c33c368/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Cyst-Removal-Inset_jpg)

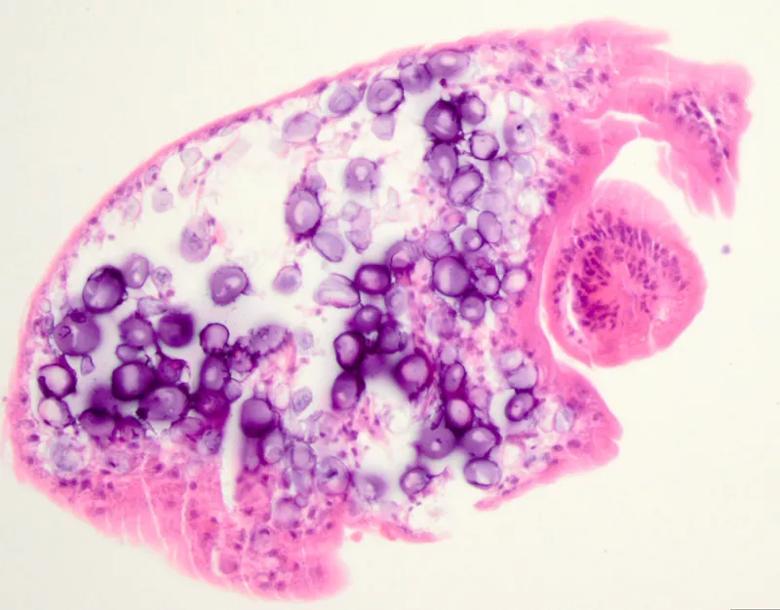

The specimen was sent to pathology, which confirmed the presence of calcareous corpuscles, pathognomonic for cestode infection. This finding was instrumental in extending the patient’s treatment with antiparasitic medication.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2f59e9df-57c3-4191-a82f-32aff6276320/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Slide-15a_jpg)

Calcareous corpuscles (purple ovals) are pathognomonic for cestode infection. The circle on the right is likely the head of the parasite.

Six weeks later, the lesion was healing well, with a ring around the area, indicating fibrosis. The patient’s visual acuity was 20/25. She had completed her course of treatment and was in good overall health. Now two years later, the patient continues to do well.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/463d72e5-8c68-4c77-9077-2d07867a3e39/20-EYE-1874750-CQD-Retina-Worm-Case-Slide-16_jpg)

Six weeks postop, the lesion is healing well, with a ring around the area, indicating fibrosis. The area to the left is the surgical extraction site that has been lasered.

This case illustrates the role of ophthalmologists in helping diagnose and treat patients with systemic infection or inflammatory disease. The presentation of such conditions in the eye — and our ability to interpret findings — can help guide treatment. In this situation, our role was helpful in monitoring the patient after diagnosis and then adjusting her therapy after performing a procedure that showed her infection had not resolved completely.

Advertisement

Our communication and collaboration with infectious disease colleagues helped this patient make a complete recovery.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A review of pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment options

How computational tools and personalized biomechanics can improve keratoconus detection, ectasia risk assessment and surgical outcomes

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists