Screen patients seeking care for chlamydia, gonorrhea

Research finds low rates of positive test results

Lingulectomy removes infection when antibiotics fail

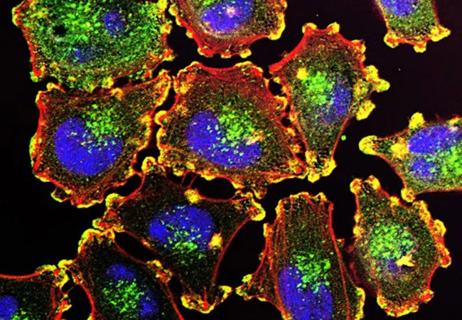

Researchers have developed immunoprofiles for an emerging disease with a mortality rate as high as 27%

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A brief review of expert guidance on what’s known and unknown

Screening assay effective across all stages, can identify tissue of origin

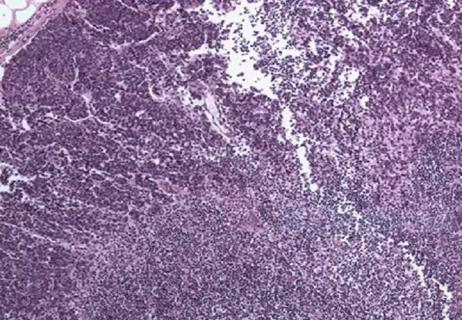

Leveraging the prognostic significance of sentinel lymph node biopsy histologic patterns

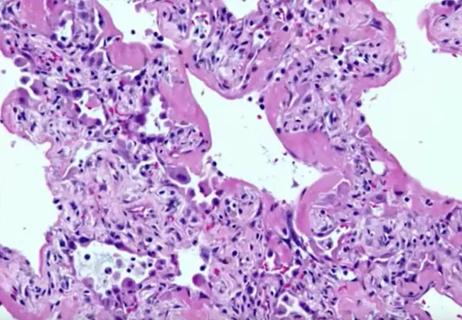

ARDS, diffuse alveolar damage and hypoxia

Molecular study suggests an update to AJCC guidelines

Findings from one of the first published case series

Advertisement

Advertisement