Bottom-of-sulcus cortical dysplasia is easy to miss without advanced imaging

By Elaine Wyllie, MD, and William Bingaman, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In patients with severe drug-resistant epilepsy, an unrevealing magnetic resonance imaging study (MRI) makes surgical planning much more challenging even if other indicators suggest the possibility of a focal epileptogenic zone. It is important not to miss any previously unappreciated subtle clues on the MRI that could confirm the case for surgery, as underscored by the following case study featuring a video that profiles the findings from advanced neuroimaging.

Daniel (a pseudonym) had explosive onset of epilepsy at age 3.5 years. Until then he was developmentally precocious — “a bright star at school and home,” his mother reported. With the onset of his severe epilepsy, his family’s world was shattered.

Daniel’s initial seizures had features suggestive of focal origin within the right hemisphere. At seizure onset, he appeared fearful or announced that he was having a seizure, indicating an aura. Seizures then had a gelastic component, with a tonic forced smile and unnatural laughter and then forced turning of the head and eyes to the left. Seizures lasted about 30 seconds and recurred 10 to 15 times a day, despite trials of several anti-seizure medications. A year later, epileptic spasms also emerged, involving injurious unprotected forward falls with cheek or tongue bite, recurring many times every day. Daniel now required constant supervision, and his family’s daily life was consumed by his condition.

Daniel also developed epileptic encephalopathy. Learning stopped completely, and he became inattentive, impulsive and aggressive.

Advertisement

In his home country, doctors suspected focal epilepsy from somewhere in the right hemisphere, but because MRI was interpreted as normal, a surgical strategy was unclear. The plan was to next undergo invasive evaluation with subdural electrodes. At that point he was referred to Cleveland Clinic.

We met Daniel at age 4.5 years. He wore a helmet to protect his face and head from the daily seizures with injurious falls. Careful trials of eight anti-seizure medications conducted previously had provided no relief. His development was regressing, and his behavior was difficult.

Below is a series of EEGs (Figure 1) presenting key electroencephalographic features from Daniel’s evaluation at Cleveland Clinic.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8d0ff220-fe4d-4557-be7a-e6cfff9ca586/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset1)

Figure 1 (part 1 of 9). Segments of the awake EEG showed normal background activity.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e97b3ca7-5a38-4ccb-a9d4-2d3b88855b66/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset2)

In contrast, the asleep EEG showed a nearly constant hypsarrhythmia pattern.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a3fdc08c-3c11-499d-bdff-dd0d3be7b6bb/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset3)

In wakefulness, the EEG showed generalized slow spike-wave complexes…

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c9ea0240-2254-444b-a611-2b4bcfed2544/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset4)

…but close examination also revealed focal slowing and sharp waves from the right frontal and midline regions (arrows).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ac46ccba-ced8-4e04-94a9-c930b4521c04/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset5)

EEG seizures began with a similar pattern of generalized sharp waves and then focal slowing in right frontal and midline regions during the smile.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/97953aa8-f9a5-464b-aaa1-340132c0d269/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset6)

Six seconds later, the right frontal slowing became more pronounced.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c88d522d-e304-4399-a2a5-9bccd2c0950f/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset7)

The EEG then became nonlocalized and remained so through the phase at 20 seconds when he cried out…

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/34fc909d-e30b-4cbe-b3ae-6497a146603a/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset8)

…during the flexor spasms with head turned to the left…

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2f5c3617-76a1-492e-8d04-7408b90d65d4/when-epilepsy-surgery-is-indicated-inset9)

…and until the seizure ended 75 seconds after onset.

With the right frontal elements on ictal and interictal EEG, and the seizure features including aura and left version, it appeared that Daniel might be a candidate for epilepsy surgery. But the presumably normal MRI posed a serious challenge, especially because most of his ictal and interictal epileptiform discharges were generalized.

The subtle focal features on EEG and semiology led to a closer look at the right frontal lobe with advanced neuroimaging techniques.

Close inspection of the suspected area on MRI revealed a subtle, small funnel-shaped extension of abnormal cortex with an indistinct gray-white junction protruding from the bottom of the sulcus. This same area of gray matter abnormality was highlighted by the computational technique of voxel-based morphometry. This correlated with a region of severe focal hypometabolism on positron emission tomography (PET), which was also maximal at the bottom of the right superior frontal sulcus.

Advertisement

Ictal single-photon emission computed tomography showed convergent findings, with focal increased blood flow in the same area. Each of these imaging modalities highlighted a region of focal cortical dysplasia at the bottom of the right frontal sulcus, which added precision to the localization suggested by video EEG.

These findings from advanced imaging analysis are detailed in the 57-second video below, narrated by Elaine Wyllie, MD.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://www.youtube.com/embed/_T3fLy3-VJ4?feature=oembed)

Bottom-of-Sulcus Cortical Dysplasia: Insights from Advanced Neuroimaging Techniques

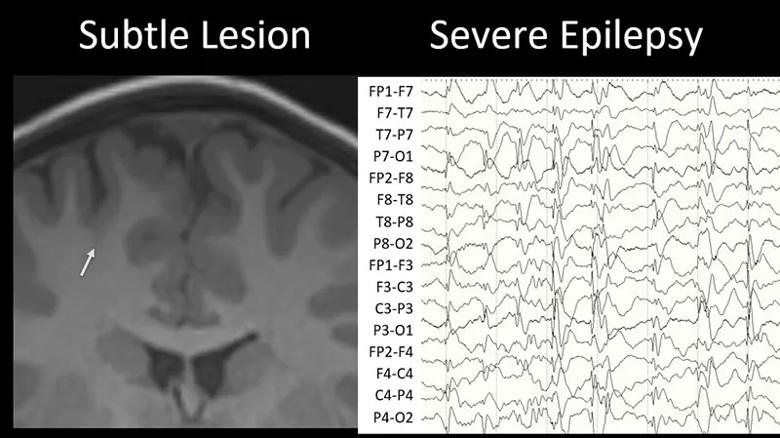

The lesion seen on MRI was small and subtle (as illustrated in the above video), while the EEG showed abundant nonlocalized epileptiform discharges (Figure 2).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/10cc362f-63e6-4211-bad0-540a0120f682/21-NEU-2275410-CQD-Display-2-800x449-1_jpg)

Figure 2. (Left) The arrow on this coronal MRI points out the subtle bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia extending from the depth of the right superior frontal sulcus. (Right) EEG showing a nonlocalized hypsarrhythmia pattern during sleep.

Could such a small and subtle lesion cause such severe epilepsy, with daily seizures, epileptic encephalopathy, generalized slow spike-wave complexes, and hypsarrhythmia during sleep? Could resecting this tiny lesion solve the boy’s problems?

Based on experience at Cleveland Clinic (published in Neurology [2007;69(4):389-397]) and at other centers, we know the answer to both of these questions is yes. When an early lesion such as a malformation of cortical development interacts with the developing brain, widespread patterns of epileptogenicity may result, including hypsarrhythmia or slow spike-wave complexes. Surgery in such cases is usually successful.

Bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia has clearly been defined as a favorable substrate for epilepsy surgery. These lesions are intrinsically epileptogenic, with almost continuous localized rhythmic interictal epileptiform discharges and seizures seen on scalp and invasive EEG. Furthermore, they usually harbor no normal function, as evidenced by hypometabolism on PET, perilesional but not intralesional activation on functional MRI and displaced motor functions on cortical stimulation. Resection typically results in seizure-free outcomes with no new neurologic deficits.

Advertisement

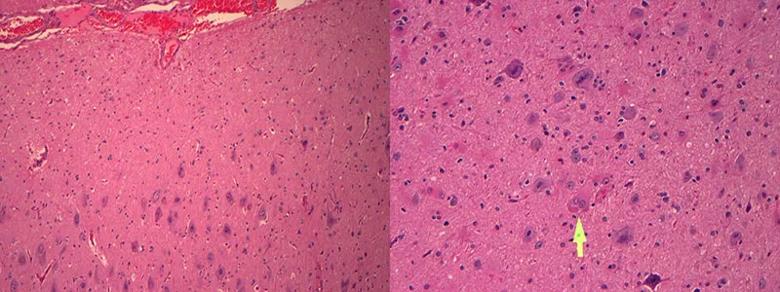

The histopathology of bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia is usually type II focal cortical dysplasia, with architectural disturbance, dysmorphic neurons and balloon cells. Increasing evidence points to a genetic etiology in many patients, involving mTOR pathway dysregulation.

As in Daniel’s case, the lesion is often very subtle and initially missed, often delaying surgery for years. It is helpful to use higher-intensity MRI, focus attention on the suspected region and co-register MRI with PET.

Daniel’s advanced neuroimaging findings provided all the information needed to proceed to surgery with confidence without invasive study.

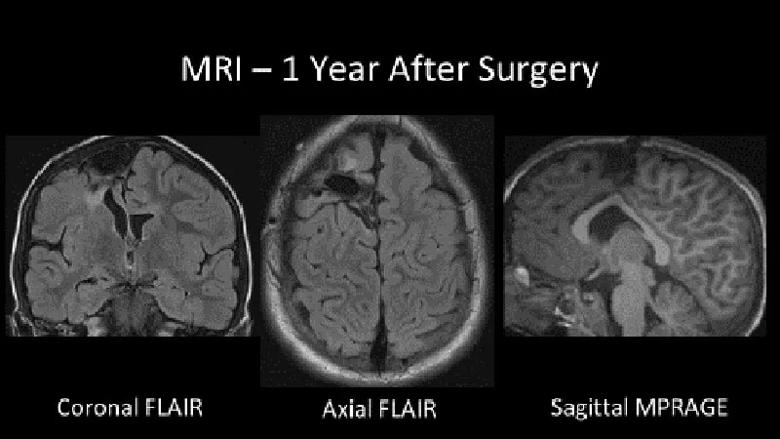

He underwent stereotactic resection of the cortical dysplasia at the bottom of the right superior frontal sulcus; the margin of resection was extended inferiorly based on intraoperative electrocorticography (Figure 3). Multimodality imaging techniques allowed intraoperative stereotactic display of all the localization studies, and surgery focused on localizing and removing the abnormal cortex seen on the preoperative MRI scans. At the end of surgery, the EEG showed no epileptiform discharges. He recovered uneventfully and was discharged from the hospital on the second postoperative day.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b8a9dde2-e1bc-4616-b2f8-1f7e7a5808eb/21-NEU-2275410-CQD-Display-3-800x450-1_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative MRI showing the resection of the bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia in the right superior frontal sulcus, with inferior extension guided by intraoperative electrocorticography.

Histopathology showed focal cortical dysplasia type IIb, with both dysmorphic neurons and balloon cells (Figure 4).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/56250c07-1903-403d-87cf-bb30d686ef9c/21-NEU-2275410-CQD-Display-4-800x300-1_jpg)

Figure 4. Postoperative histopathology showing dysmorphic neurons (left panel) and balloon cells (arrow in right panel) characteristic of focal cortical dysplasia type II.

One week after surgery, EEG rhythms were completely normal (Figure 5). Daniel’s seizures and epileptic encephalopathy completely resolved.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/65cdd9f6-8ddd-4dc1-9616-07f83f6919ce/21-NEU-2275410-CQD-Display-5-800x432-1_jpg)

Figure 5. Daniel’s postoperative EEGs showing no interictal epileptiform discharges.

One year later, Daniel remains seizure-free on a regimen streamlined to a single seizure medication. A 24-hour EEG recording was completely normal. He is back to being a bright star — active, playful and at the top of his class.

Advertisement

Recognizing a subtle lesion such as bottom-of-sulcus dysplasia may be the most exciting and rewarding way to overcome a presumed negative MRI. This lesion is often difficult to appreciate during routine review, but by using higher-intensity MRI, focusing our attention on the candidate region, and co-registering the MRI with PET, the yield may be increased. The effort is worthwhile, because resection is successful for over 80% of patients, with no need for invasive electrodes. By heightening our awareness of this subtle MRI finding, together we will help more patients than ever before.

Dr. Wyllie is Professor of Neurology at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and a pediatric and adult epilepsy specialist in Cleveland Clinic’s Epilepsy Center. Dr. Bingaman is Professor of Neurological Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and Head of Epilepsy Surgery in the Epilepsy Center.

Advertisement

A case study in pairing imaging acumen with subspecialty expertise to yield answers and symptom relief

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology