Phenotypic clustering study reveals four distinct disease trajectories

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/73e86c8c-96b0-41f3-abe3-3aac26515107/tuberous-sclerosis-disease-trajectories-1)

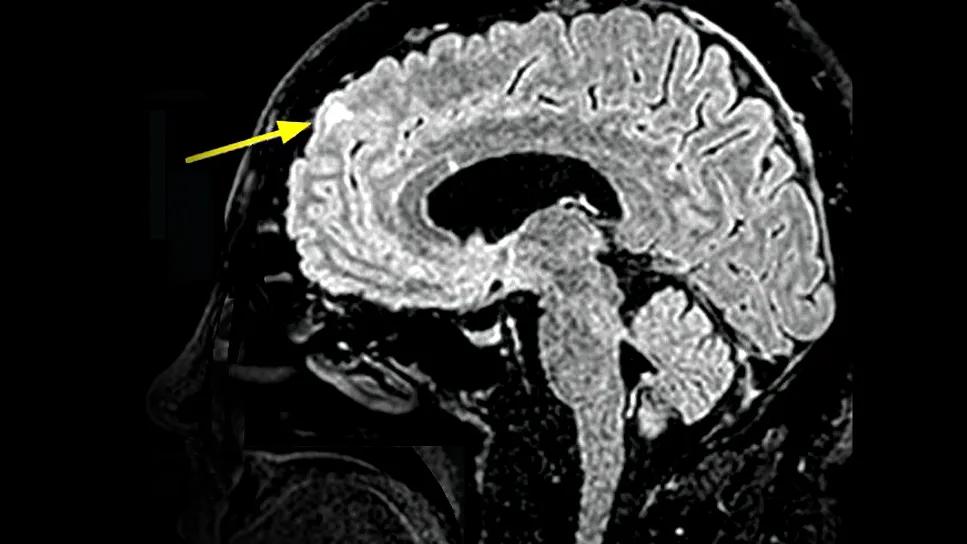

brain MRI with arrow pointing to a cortical tuber

For the first time, researchers have classified tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) into distinct subtypes, each associated with its own specific gene mutations, disease trajectories and overall prognoses. The findings, published in Brain by Cleveland Clinic investigators, underscore the heterogeneity of TSC and hold potential to guide future disease surveillance, treatment protocols and clinical trial design.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Despite gains in our understanding of the phenotypes with which TSC may present, we wanted to better understand genotype-phenotype correlations in this disorder so that we could better advise patients and their families on what to expect and to enhance treatment strategies,” says the study’s senior author, Ajay Gupta, MD, Section Head of Pediatric Epilepsy at Cleveland Clinic.

TSC is a multisystem autosomal dominant disorder characterized by a wide range of clinical presentations including neurological manifestations, such as seizures and neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as neuropsychiatric conditions and development of hamartomas in various organs. The heterogeneity arises from germline variants in the TSC1 or TSC2 genes, leading to dysfunction in the mTOR pathway. Most cases manifest during infancy or childhood.

Families with TSC gene mutations face a lifetime of uncertainty. Despite advances in genetic testing, clinicians generally cannot tell their patients with TSC which of the disease’s many possible symptoms may arise from their mutation.

In an attempt to reduce that uncertainty, Dr. Gupta and Cleveland Clinic co-investigators analyzed the TSC Natural History Database, a prospective, multicenter U.S. repository of well-characterized patients in the TSC Clinical Network, in which Cleveland Clinic is a participating center. To assess for patterns in how the disease manifested among the database’s 947 individuals with clinically confirmed TSC, the researchers used an unbiased, phenotype-driven clustering approach. They focused on 29 clinical features to group patients, using a statistical method known as logistic principal components analysis as their primary method and hierarchical clustering to confirm consistency of results.

Advertisement

The analysis identified four main clusters of TSC cases, each with specific gene mutations and disease trajectories:

The study also assessed associations between these phenotypic clusters and the underlying genotype (TSC1 or TSC2 gene variants). Although no statistically significant associations were found with overall TSC1/TSC2 mutation status or variant type, the researchers identified associations with variant location within specific protein domains. For instance:

Advertisement

Variants affecting the Rho domain of TSC1 (exons 5-12) were significantly more likely to be found in Cluster 1 (angiomyolipoma-predominant) and significantly less likely in Cluster 4 (milder phenotype).

Variants affecting the TSC1 binding domain (exons 2-12) of TSC2 were also significantly more likely to be found in Cluster 1 and significantly less likely in Cluster 4.

The authors conclude that their findings “establish the foundation for larger, prospective studies aimed at validating and refining the proposed disease subtype clustering in TSC.” While acknowledging this need for additional validation, the researchers are excited about the impact TSC subtyping could have for patients and their families, in terms of more personalized management.

“Understanding how our patients’ genetics influence their symptoms will help us ensure that our patients with TSC have everything they need — and only what they need — when it comes to treatment and surveillance,” Dr. Gupta says.

These new insights into disease trajectories have implications for clinical trial design as well, adds co-investigator Andrew Dhawan, MD, PhD, a Cleveland Clinic neuro-oncologist who monitors adults with TSC for brain tumors (benign and cancerous) and treats them accordingly.

“Someone interested in developing a drug for TSC patients with brain or renal disease would probably only want to enroll those TSC patients who are going to have the most severe brain and renal symptoms,” Dr. Dhawan explains. “Giving the therapy to a patient in a TSC cluster not marked by renal manifestations could skew the clinical trial results because the drug wouldn’t make much of a difference for such a patient. These findings should help us refine patient selection to improve future trials.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges

Rare genetic disorder prevents bone mineralization

Oral medication reduces epistaxis and improves quality of life for patients with rare vascular disorder

A recently published case series highlights the broad range of laryngeal findings that can present among individuals with EDS

The disorder can greatly impact patients’ quality of life, but sclerotherapy and a multidisciplinary approach to care can be life-changing

National database study reveals insights into survival outcomes

First-ever procedure restores patient’s health

Cancer drug helps treat decades-long symptoms in patient with complicated lymphatic issue