Behavioral modifications to reduce severity of symptoms

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/89b8d191-4e83-4176-b29b-a3f7433306b4/20-RHE-1356-exposomeGrid-650x450-1_jpg)

20-RHE-1356-exposomeGrid-650×450

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Over the past generation we have witnessed marked progress in our understanding of the inflammatory process and how it relates to health and disease. While intermittent inflammation in reaction to injury or infection can aid survival, chronic, lower-grade inflammation has been shown to be associated with chronic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and psoriasis.1

The biologic underpinnings of how behavior influences integrated immune health are becoming clearer and involve complex biologic pathways. Advances in genomics have helped us identify physiological patterns of biological differences between individuals with chronic stress (i.e., loneliness, poverty, bereavement, post-traumatic stress disorder, etc.) and those without such chronic stressors. Studies show that the genes upregulated in adversity are associated with inflammation, and those downregulated in adversity are enriched with transcripts related to Type 1 interferon responses.2

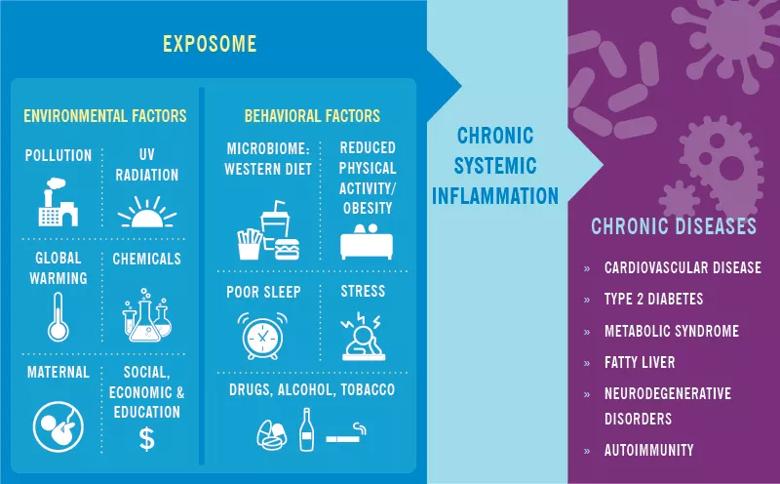

Additionally, the literature suggests both endogenous and non-endogenous factors are associated with chronic inflammation.1 While the endogenous factors, such as aging, oxidative stress and DNA damage, are difficult to control on an individual level, the non-endogenous factors, such as microbiome dysbiosis, stress, environmental pollutants,3 obesity and physical activity, may be altered to both help lower the inflammatory response, but also to potentially improve health and relieve symptoms from some of these disorders. In the case of rheumatoid arthritis for example, traditional treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs might be complemented with behavioral interventions, such as an anti-inflammatory diet, an exercise plan and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b678cdfa-5405-48d9-97f4-00694d63d562/19-RHE-1356-chronic-systemic-inflam-exposome-inset-CQD_jpg)

A growing body of data derived from preclinical investigations as well as observational and interventional studies provides evidence that the Western-type diet (WD) is a major driver of chronic, low-grade, metabolic inflammation.4 The WD includes highly processed, convenience foods and sweetened beverages – all of which are high in calories, sugars, trans fats and saturated fats, salt and other food additives. The mechanisms contributing to these pro-inflammatory effects are multiple. First, consumption of the WD has been demonstrated to lead to both quantitative and qualitative changes in our microbiome, which in turn helps shape our integrated immune response. Such dietary patterns also lead to disruption of the gut-barrier integrity,5 allowing harmful translocation of microbial products, which can induce inflammation.

Finally, perhaps one of the most remarkable developments in our understanding of the diet-inflammation axis is its demonstrated capacity to serve as a danger signal to the innate limb of immunity. Innate immunity — our early line of defense against infectious danger signals — was traditionally understood as lacking a memory component.6 Over the past decade, mounting evidence has demonstrated that innate cells (e.g., myeloid cells) can “memorize” inflammatory encounters with pathogens, creating long-lasting changes in the way the cells respond to subsequent challenges. Similarly, a series of studies have demonstrated that innate immunity can also respond with “trained memory” to sterile challenges, such as uric acid and cholesterol crystals.1,7 Bringing this back to our dietary patterns, based on pre-clinical experimental modeling, the innate immune system appears to mistakenly recognize the WD as a threat and responds vigorously with an inflammatory response as result of metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming.

Advertisement

The proinflammatory diet pattern is associated with increased seropositive RA risk in women ≤ 55 years old, according to a large study of over 170,000 women with up to 30 years of follow-up.8 Interestingly, the association can be partially attenuated by decreased body mass index. No association between the proinflammatory diet pattern and RA risks was found in women over the age of 55. Recent reviews have supported an adjunctive role of achieving a prudent diet enriched with saturated fat content and minimized for high salt content and stripped carbohydrates as an important adjunct in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis.9 This same review further asserts that clinicians who treat immune-mediated diseases are poorly prepared to provide such counsel. Future research might focus on the impact of an anti-inflammatory diet (i.e., a high monosaturated fat/saturated fat ratio; high consumption of whole grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables; low consumption of meat; moderate consumption of milk and dairy products) on RA risk and symptom severity and quality of life.

We are beginning to see more high-quality studies demonstrating not only the capacity of diet,8 exercise,10 sleep14 and stress modification12 to influence biomarkers of inflammation, but also their capacity to influence many of these diseases of chronic inflammation and general quality of life. In one small randomized clinical trial (N = 20), patients who practiced Tai Chi twice weekly over 12 weeks, reported statistically significant improvements in scores of disability, vitality and depression compared with a control group.10 Another study (N = 131) found that RA patients who received eight weekly, two-hour-long cognitive behavioral therapy sessions for pain management had decreased mitogen-simulated levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) production and improved self-reported pain control at six months.11 In a New Zealand study of patients with RA (N = 51), participants randomized to a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention showed greater improvements in the four-variable Disease Activity Score in 28 joints-C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) immediately following the intervention, and at four- and six- month follow-up.12 These early studies are intriguing. Certainly, larger RCTs of behavioral interventions aimed to increase quality of diet, sleep, exercise and mindfulness should be explored.

Advertisement

I am writing a six-part series for Consult QD on systemic inflammation and chronic disease that will explore the role of behavioral modification in addressing chronic inflammation and immune health, and how healthcare providers, payers, the pharmaceutical industry and patients can come together to improve global health. Topics will include diet, exercise, sleep, chronic stress and behavioral economics.

Advertisement

Dr. Calabrese (@LCalabreseDO) is Director of the R.J. Fasenmyer Center for Clinical Immunology at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being