The identification of a novel disorder: the VEXAS syndrome

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

You are asked to see a 72-year-old male who has just moved to your community. Three years ago he developed a systemic inflammatory illness characterized by fevers, skin lesions and arthralgias/arthritis of the knees, ankles, wrists and elbows. Labs were notable for a macrocytic anemia, elevated sedimentation rate and C- reactive protein, with negative RF, anti-CCP, ANA and ANCA. Biopsy of the skin lesions revealed a neutrophilic dermatosis. Two years ago he developed dyspnea with pulmonary infiltrates unrelated to infection. Last year he had a deep venous thrombosis (DVT) with no evidence of a hypercoagulable state. He has been treated with prednisone on which he improves but requires doses above 20 mg/day and he has also received methotrexate and azathioprine without benefit. He is now hospitalized after developing a fever, thrombocytopenia and worsened joint pain while on prednisone 25 mg/day. Assessment for infection has been negative. He notes new swelling over the nasal bridge and external ear. His medical team consults you for the question of whether he has a rheumatic disease.

In considering the clinical features of this patient, the recent development of nasal and ear swelling raises the possibility of relapsing polychondritis. Relapsing polychondritis is a complex disease characterized by inflammation of cartilage within the ear, nose, joint and respiratory tract often with multisystem disease involving the eye, skin, nerve, heart and vascular system.1-3 There is no single confirmatory test for relapsing polychondritis with the diagnosis being established by the constellation of clinical findings, laboratory data, imaging and when possible biopsy of an involved cartilaginous site.

Advertisement

While many of this patient’s symptoms and signs could fit for relapsing polychondritis, others such as the pulmonary infiltrates, DVT and hematologic findings raise the question of whether there may be a different underlying diagnosis.

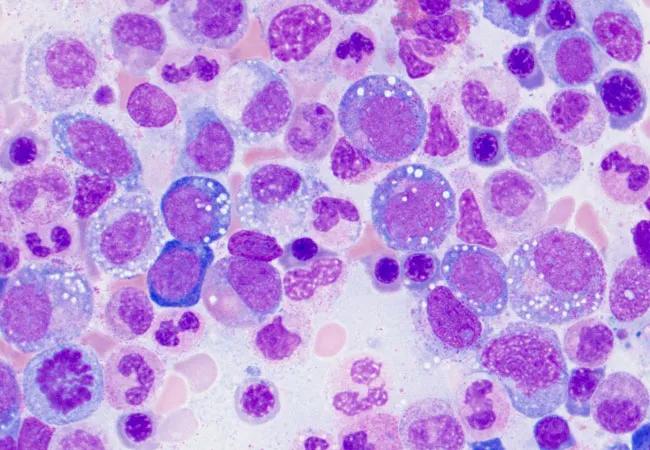

An exciting discovery recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine was the identification at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of a novel disorder that connects seemingly unrelated adult-onset inflammatory syndromes.4 This disorder has been named the VEXAS (vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome. In this study, 25 men were identified that possessed somatic mutations affecting methionine-41 in UBA1, the major E1 enzyme that initiates ubiquitylation. These patients presented with a treatment-refractory inflammatory syndrome that developed in late adulthood with clinical features that included fevers, neutrophilic cutaneous and pulmonary inflammation, chondritis and vasculitis together with hematologic abnormalities of cytopenias, vacuoles in myeloid and erythroid precursor cells, dysplastic bone marrow, or multiple myeloma.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cd9e22d0-ba92-4372-8cd9-a70dc5baf598/20-RHE-2006260-Langford_VEXAS-syndrome-CQD-650x450-1_jpg)

Vacuoles in myeloid cells in a patient with VEXAS (image courtesy of Katherine Calvo, MD, PhD, and Marcela Ferrada, MD, National Institutes of Health).

From a diagnostic standpoint, recognizing the constellation of clinical manifestations is the first essential step in identifying patients with the VEXAS syndrome. For rheumatologists, the VEXAS syndrome should be considered in a male patient with characteristics that suggest relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Sweet syndrome, adult onset Still’s disease, or giant cell arteritis which is occurring in conjunction with one or more of the following:

Advertisement

While these have been the currently identified manifestations of the VEXAS syndrome, additional clinical features may be found as more patients are tested and identified. For patients who have bone marrow biopsies performed, the precursor cells should be carefully examined to look for vacuoles which are characteristic of the VEXAS syndrome. Genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed by contacting the NIH team who described the VEXAS syndrome.

In the 25 described patients with the VEXAS syndrome, treatment refractory disease was typical. Glucocorticoids at high doses often provided improvement with many patients having also received multiple other immunomodulatory agents. Ten of the 25 patients died either as a result of their disease or from treatment-related complications, which speaks to the severe nature of this disorder. At this time the optimal treatment for the VEXAS syndrome remains unclear although the article notes that approaches to target the somatic process should be considered.

The identification of the VEXAS syndrome is a very important discovery for multiple reasons. This work utilized a genotype-first, phenotype-neutral strategy to identify the cause of a severe adult-onset disease, an exciting approach which could open the door for many future insights into human disease. Significantly for patient care, the VEXAS syndrome provides a diagnostic explanation for a complex range of seemingly unrelated clinical features. Recognition of this disorder will help physicians, patients and their families in having the first step of knowing the cause of their illness and in beginning to work together toward an approach to treatment.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being