Get objective results when clinical findings, imaging and genetic testing are contradictory or inconclusive

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/fa414b93-e670-4db6-a356-3cd06e7cc79f/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_119-805x536-1-jpg)

Electroretinography

A 13-year-old female originally was diagnosed with cone dystrophy. She had progressive vision loss, dyschromatopsia, and difficulty in bright and dark lights. Her imaging and clinical exam were highly suggestive of achromatopsia. However, electroretinography (ERG) showed severely depressed function of the central macula with only mildly abnormal panretinal cone dysfunction — findings consistent with a maculopathy, not a disease affecting all cone photoreceptors, like achromatopsia. Results of ERG led the patient to have genetic testing for maculopathy, which revealed mutations in the ABCA4 gene and confirmed the diagnosis of Stargardt disease.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 42-year-old male was referred for cone dystrophy vs. optic nerve disorder. The clinical exam suggested cone dystrophy or achromatopsia. Imaging showed mild abnormalities but was equivocal. Genetic testing was inconclusive, detecting a previously unpublished variant of unknown significance in a gene that may cause cone-rod dystrophy. ERG indicated that the patient’s cone function was almost completely extinguished, supporting the diagnosis of cone dystrophy.

When clinical findings, imaging results and genetic testing are contradictory or inconclusive, visual electrophysiology — ERG and visual evoked potential (VEP) tests — can help diagnose eye disease.

“Disorders that affect cone pathways in the retina can mimic optic neuropathy,” says Alex Yuan, MD, PhD, a retina specialist at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. “Both can affect color and central vision. They sometimes look identical clinically, especially in very young patients.”

While genetic testing is considered the gold standard in diagnosing inherited retinal and optic nerve disease, it isn’t foolproof. Clinicians’ understanding of the connections between genetics and disease presentation is growing rapidly, but sometimes a patient’s genetic test results will detect a variant of unknown significance, where there isn’t enough evidence to link the variant to a disease. Other times, a patient may have a mutation in a gene that hasn’t yet been characterized and isn’t tested in the panel.

Even diagnostic stalwarts like optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fundus autofluorescence rely on pattern recognition — whether an area of the retina looks abnormal or layers of the retina seem too thin — which provides anatomic data but not functional information. And visual field testing can be skewed by a patient’s ability to participate correctly, among other factors.

Advertisement

“Visual diagnostic testing is often subjective,” says Rebecca M. Schur, PhD, an ophthalmic electrophysiology specialist at the Cole Eye Institute. “However, visual electrophysiology provides an objective functional measurement of how different pathways of cells in the visual system are communicating.”

During a visual electrophysiology assessment, recording leads are attached to a patient’s forehead, temples and sometimes back of the head. A thread-like wire electrode (a DTL electrode) is placed on the cornea. An anesthetic eyedrop prevents irritation.

For ERG and VEP tests, patients watch various types of light stimuli. For some tests, patients look into a Ganzfeld dome, which flashes lights in different patterns, speeds and intensities to excite different cellular pathways in the eyes. Some tests are conducted in the dark and the light to record rod and cone function, respectively. For other tests, patients watch a screen with a flickering high-contrast pattern (like a black-and-white checkerboard).

During the tests, electrical signals within the patient’s visual system are recorded, much like an electrocardiogram.

“The ERG and VEP are two different tests, but we record them at the same time,” explains Dr. Schur. “The ERG measures activity of the retina. The VEP measures activity of the optic nerve. Different variations and combinations of tests help us tease out what is happening in different parts of the eye, in the macula, nerve, cones and rods.”

The Cole Eye Institute has used visual electrophysiology for clinical diagnosis for years, but in 2018 added an array of newer test variations. Today there are standard tests — full-field ERG (assessing the entire retina), multifocal ERG (assessing the macula and/or other specific areas of the retina), pattern ERG (assessing the central retina) and VEP (assessing the optic nerve) — as well as numerous specialty tests.

Advertisement

“We also can offer patients more tests that are currently being researched,” says Dr. Yuan. “For example, the photopic negative response test, while not yet validated, can help detect progression of glaucoma.”

Tests can be administered even for the youngest patients, with or without sedation.

“We’ve been able to test babies as young as 2 months old, asleep in their parent’s arms,” says Dr. Schur. “Unlike reading an eye chart, visual electrophysiology requires no patient input.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b3abf715-0cb0-4a68-8968-4cab8796371e/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_015-805x539-1_jpg)

Rebecca M. Schur, PhD, an ophthalmic electrophysiology specialist at the Cole Eye Institute attaches recording leads to a patient in preparation for electroretinography (ERG) and visual evoked potential (VEP) testing.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/856d1902-e27a-4bd4-8c3c-ce0a5949c089/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_006-805x537-1_jpg)

Sensors are attached to the patient’s forehead, to the temples and over the eyes to measure electrical signals transmitted by the retina.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/44a513ec-8c55-4702-8e55-393b9853962e/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur-inset_jpg)

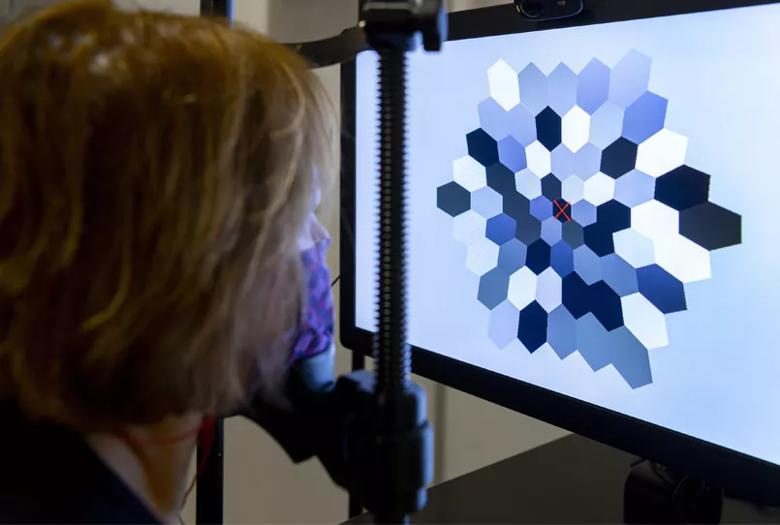

A patient watches a pattern on a screen during a multifocal ERG test. Each hexagon in the pattern is rapidly turned black or white and projects an on/off pattern onto the retina. A map of the macula’s responses to each hexagon is reconstructed to identify patterns of retinal dysfunction.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b2599303-d3d4-42c4-abb8-986bf17d3c37/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_081-805x534-1_jpg)

A patient watches a checkerboard pattern on a screen during a pattern ERG and VEP test. Sensors attached to the scalp, to the forehead and over the eyes measure activity of the macula and the optic nerves.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4a86acf1-3970-4324-8716-dedd4a5ae968/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_038-805x537-1_jpg)

Dr. Schur monitors responses during VEP testing.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/90261138-6f83-499b-a7ae-ac0f37e25d72/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_092-805x537-1_jpg)

A patient prepares for full-field ERG testing in the Ganzfeld dome. The Ganzfeld dome delivers uniform flashes of light to illuminate the retina. Different pathways within the retina can be stimulated by varying the flashes’ intensity, speed, color and level of background light.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/fa414b93-e670-4db6-a356-3cd06e7cc79f/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_119-805x536-1_jpg)

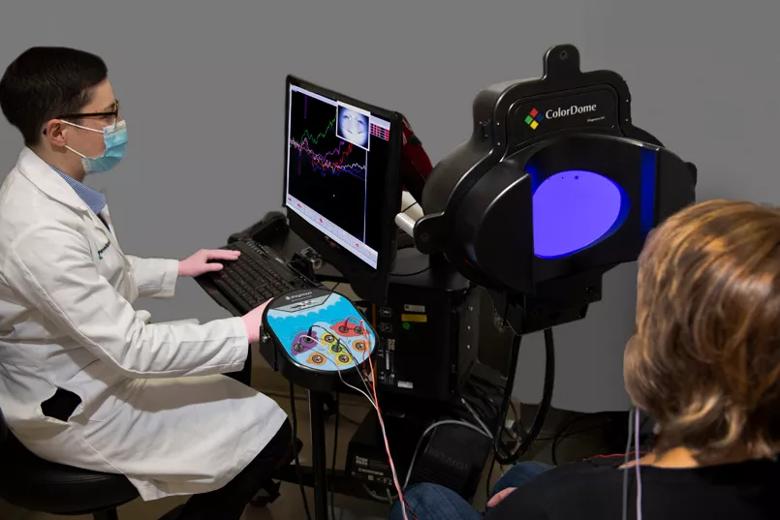

Dr. Schur monitors a patient’s responses during full-field ERG testing.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e53cad12-8cce-464a-bfb9-d0aa071384c6/21-EYE-2611239-CQD-Electroretinography_Yuan-Schur_124-805x552-dk_jpg)

A patient undergoes scotopic (dark-adapted) full-field ERG testing. Scotopic full-field ERG isolates the rod responses, which are mixed with cone responses in the light. The testing room is completely dark during this portion of the test, with only a dim red light from the computer.

According to Dr. Yuan, electrophysiology should be considered for ophthalmology patients when:

“Some practices have hand-held versions of ERG or VEP technology, which can be helpful in some situations,” says Dr. Yuan. “But in other cases, you need a full suite of testing capabilities, with specialized equipment and experts to interpret results correctly. At the Cole Eye Institute, we evaluate patients from all over the U.S., many who come here for second opinions and often leave with unexpected information about their condition.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A review of pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment options

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

It’s the first step toward reliable screening with your smartphone

Fixational eye movement is similar in left and right eyes of people with normal vision

Oral medication may have potential to preserve vision and shrink tumors prior to surgery or radiation

A new online calculator can determine probability of melanoma

Only 33% of patients have long-term improvement after treatment