Boy saved by procedure typically performed in adults

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e8206fe1-1037-4e08-b1fd-c6cc86a8a8e4/17-NEU-4426-Uchino-Defuse3-Trial-650x450_jpg)

17-NEU-4426-Uchino-Defuse3-Trial-650×450

When a healthy 7-year-old boy began speaking gibberish and laid down while taking a break from his soccer game, his mother rushed him to an emergency room near the playing field in a small town south of Cleveland. Results of a CT scan and an MRI confirmed that he had suffered an arterial ischemic stroke (AIS). With almost five hours having passed from the time of stroke, the boy wasn’t eligible to receive intravenous (IV) clot-busting drug tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). At that point, Cleveland Clinic Pediatric Critical Care Transport was called in to life-flight him to Cleveland Clinic’s main campus where the team of Cleveland Clinic Children’s interventional neurosurgeons awaited his arrival.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

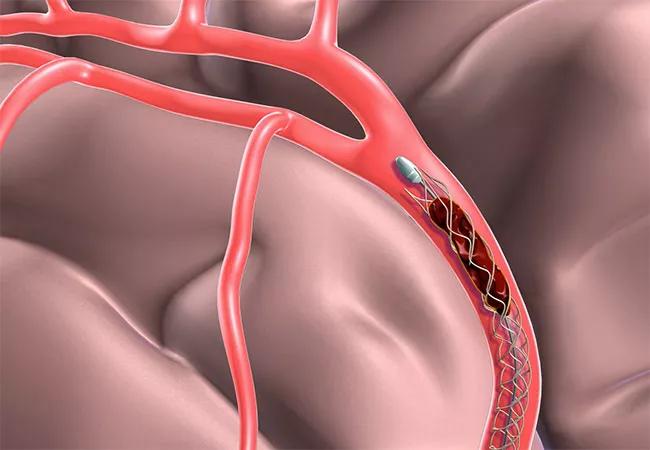

A look at the MR angiogram revealed a complete blockage of one of the main cerebral arteries in the boy’s brain, which had resulted in a significant hemiplegia (Pediatric NIH Stroke Scale score of 12), says pediatric stroke specialist Neil Friedman, MBChB, Director of the Center for Pediatric Neurosciences at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. Interventional neurosurgeon, Mark Bain, MD, used a procedure rarely performed in children called mechanical thrombectomy in which a catheter is inserted into an artery in the groin and fed up through the neck to the brain. When it reaches the clot in the artery, the basket captures and removes the clot so blood flow can be reestablished.

Dr. Bain made several attempts during the procedure to remove what the surgery team thought was a clot. On his last attempt, he advanced the guide catheter forward a little and the vessel “popped” open. The procedure was successful with recannulization of the vessel. When the patient woke up, he was able to talk haltingly. By the next day, he was playing video games and drawing on white board walls in his room. Less than a week later, he was discharged from the hospital with a significantly improved hemiplegia and Pediatric NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 3. At subsequent follow-up, he had minimal residual evidence of his stroke, with his Pediatric NIHSS score now at 0.

With no sign of trauma, tearing of the vessel or obvious clot on cerebral angiogram, Dr. Friedman says the boy’s blockage may have been the result of an entity known as focal cerebral arteriopathy (FCA) of childhood. While the exact etiology of FCA is unknown, previous studies have suggested a potential relationship to preceding viral illness and possible inflammation. He is now part of an international study that Cleveland Clinic is a participating in funded by the National Institutes of Health that is looking at the impact of infection, specifically certain viruses, in causing stroke in children.

Advertisement

Dr. Friedman says a better understanding of the potential etiology of childhood stroke, as well as potential recurrence risk, is the focus of the second Vasculopathy in Pediatric Stroke (VIPS II) study currently underway at Cleveland Clinic and 16 other centers in the U.S., Canada and Australia. VIPS II follows the first VIPS trial, which found that the greatest predictor of stroke recurrence is arteriopathy. Dr. Friedman is a co-investigator in both VIPS I and VIPS II. He notes that if inflammation does in fact play an important role in focal cerebral arteriopathies, experts want to know if treatment with steroids, for example, might improve outcomes and reduce the risk of recurrent strokes.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges