Novel collaborative approach helps patient avoid orbital exenteration

A 54-year-old woman with left eye pain, proptosis and limited ocular motility was evaluated at a non-Cleveland Clinic hospital. Following imaging and a transcranial biopsy, she was diagnosed with a GLI1-amplified spindle cell tumor behind her left eye.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

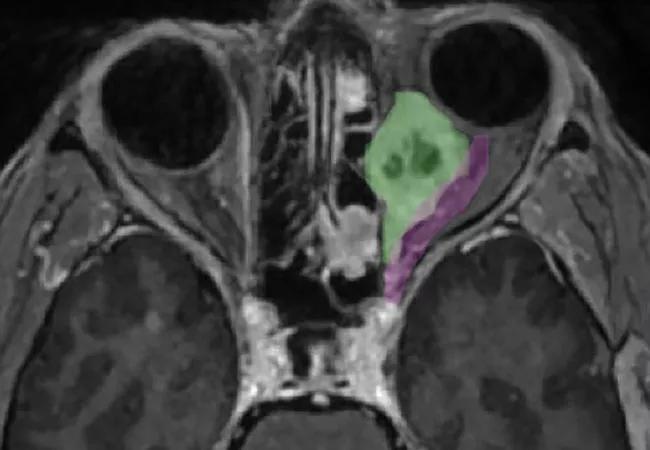

This type of tumor, while rare, previously had been reported in various head and neck sites but never in the eye. In addition to its rare presentation, the tumor was uniquely positioned, spanning from the posterior globe deep into the orbital apex.

The outside institution recommended removal of the entire left orbit. However, orbital exenteration, a disfiguring surgery for any patient, would have had additional repercussions in this case. The patient mostly relied on her left eye for vision because visual acuity in her right eye was 20/300 due to a previous retinal detachment.

To explore other treatment options, the patient presented at Cleveland Clinic, where a multidisciplinary skull base surgery team helped pioneer the endonasal removal of similar tumors. Neurosurgeon Pablo Recinos, MD, and rhinologist Raj Sindwani, MD, reviewed the case with a tumor board.

“The pathology was so rare, and the location was incredibly challenging, but Dr. Sindwani and I were confident that we could access the tumor — at least the back of it,” says Dr. Recinos, Section Head of Skull Base Surgery in Cleveland Clinic’s Rose Ella Burkhardt Brain Tumor and Neuro-Oncology Center.

Drs. Recinos and Sindwani recently published a study of their endoscopic endonasal approach to intraconal orbital tumors. A review of 20 of their patients from 2014 to 2021, the article presents the largest cohort and most experience with the surgical approach published to date.

“In this case, our one concern was how far anterior we could go,” notes Dr. Recinos. “We didn’t think we could reach far enough into the orbit to resect the front of the tumor.”

Advertisement

As a result, the team collaborated with ophthalmologist Arun Singh, MD, Director of Ophthalmic Oncology at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. All three surgeons working together would make it possible to resect a tumor that would be impossible for any one of them alone.

“Tumors like this are in a no-man’s-land that crosses the surgical boundaries of ophthalmic, brain, and head and neck specialists,” explains Dr. Sindwani. “For masses located toward the back of the eye, the endoscopic approach through the nose that Dr. Recinos and I routinely perform is very effective. For tumors extending toward the front of the eye, as in this case, it is necessary to have the expertise of all three specialists. We each bring a unique skill set and perspective to this multidisciplinary approach in which we as a team make one or more corridors to gain access to the tumor and then safely remove it, avoiding unwanted complications.”

Drs. Recinos, Sindwani and Singh recently published an article on this rare case in Orbit.

The six-hour procedure was performed in three steps:

Advertisement

“Normally, we use the corridor between the medial and inferior rectus muscles of the eye to gain access to orbital tumors,” says Dr. Recinos. “In this case, the tumor sat superior to the medial rectus, a much more challenging position. So, we developed a corridor above the medial rectus muscle and were aided by an anterior dissection by Dr. Singh.”

Drs. Recinos and Sindwani called on their experience resecting skull base tumors in the intracranial space through the nose — as well as the use of angled endoscopes and other surgical instruments designed for ear, nose and throat procedures — to successfully remove the tumor from the back of the eye while preserving the optic nerve and other critical structures.

“I have collaborated with neurosurgeons on several cases, when we needed open-skull access to remove orbital hemangiomas, for example,” says Dr. Singh. “However, it is rare for me to work alongside a rhinologist. In this case, removing the tumor required skills from three specialties. We each approached a different part of the anatomy with comfort and confidence.”

Two weeks after surgery, the patient had 20/80 vision in her left eye. Following a 30-fraction course of radiation therapy, she showed no residual disease at six months. Her vision continues to improve.

The number of tumors that require this cross-specialty coordination is quite small, say the surgeons. The tumor in this case was abnormally large compared to the orbit and touched different anatomic compartments. More commonly, orbital tumors can be removed endonasally without involvement from an ophthalmic surgeon.

Advertisement

“Today, patients often are told that their orbital tumor is inoperable or that radiation therapy is their only treatment option,” says Dr. Sindwani. “With our approach, many of these tumors can be removed. In fact, many more tumors in the medial and posterior orbit and orbital apex can be removed exclusively through the nose without any cuts or even bruises.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

It’s the first step toward reliable screening with your smartphone

Fixational eye movement is similar in left and right eyes of people with normal vision

Oral medication may have potential to preserve vision and shrink tumors prior to surgery or radiation

A new online calculator can determine probability of melanoma

Only 33% of patients have long-term improvement after treatment

Interventions abound for active and stable phases of TED