Taking the ‘waiting room of the future’ beyond clinic walls

Last year, clinicians and researchers in Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute published a proof-of-principle analysis showing that technology-enabled data capture can be integrated into routine outpatient practice to yield standardized data for informing patient care and enabling clinical research.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The approach, dubbed the “waiting room of the future,” centers on having patients with chronic neurologic conditions — in this initial study, multiple sclerosis — enter patient-reported outcomes and complete neuroperformance tests via iPads in the waiting room before their outpatient visits. The data are uploaded to the patient’s electronic health record (EHR) in real time and used by the patient’s provider to inform care management during the visit with freshly updated monitoring data. The information is also channeled, in de-identified form, to a cloud database for population-level research analysis.

As detailed in a Consult QD article from late 2019, the study’s confirmation of feasibility paved the way for a planned rollout of this approach to other outpatient populations served by the Neurological Institute. In fact, a new waiting-room-of-the-future space in the Parkinson disease (PD) clinic on Cleveland Clinic’s main campus was about to be unveiled in early spring 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic delayed completion.

“We felt we couldn’t wait to continue expanding this approach, so we decided to bring the waiting room of the future to patients where they were — at home,” says PD specialist Hubert Fernandez, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Neurological Restoration.

Capturing patient-reported outcomes wouldn’t be a particular challenge, as the Neurological Institute has been doing that for many years with its homegrown Knowledge Program data collection system and related platforms that allow patients to complete questionnaires remotely for immediate data transfer to their EHR. But capturing neuroperformance test measures would be more daunting.

Advertisement

So Dr. Fernandez worked with biomedical engineer Jay Alberts, PhD, Vice Chair of Innovation in the Neurological Institute, to accelerate an effort they already had underway to capture a number of the key biomeasures collected in the waiting-room-of-the-future protocol via a smartphone application called Digital Neurological Vital Signs, or DVS (“Digital Vital Signs”) for short.

“We had begun development of the DVS app before the pandemic to enhance Cleveland Clinic’s already extensive offering of virtual visits across the range of neurologic subspecialties,” explains Dr. Alberts. “Our experience with virtual visits had made clear that, in many cases, certain elements of the physical examination were very important to optimal delivery of neurologic care. So our aim was to bring key aspects of the physical exam to the virtual care setting. The pandemic catalyzed our efforts.”

The DVS app was developed by Cleveland Clinic researchers, clinicians and engineers to quantify a number of highly meaningful neurologic functions — hence the “vital signs” descriptor — that replicate portions of the standard physical exam. The app is downloaded by the patient for self-administration on a smartphone (Figure 1) and is designed to collect objective, quantitative data to characterize cognitive and motor functioning. “This is about at-home collection of actual neuroperformance test data, not just patient-reported outcomes,” notes Dr. Alberts.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e40bad45-b14f-4365-ad32-1c6f5f4fcc85/20-NEU-1917435-CQD-Waiting-room-of-the-future-for-Special-Report__inset-1-805x958-1_jpg)

Figure 1. The DVS app’s opening display.

The app collects functional data in four domains:

Advertisement

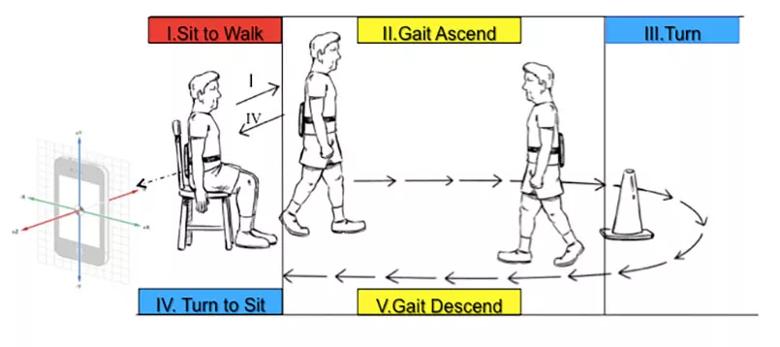

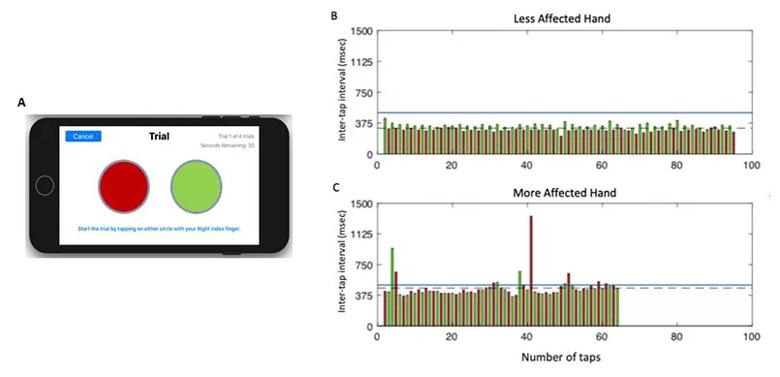

Each of the test modules takes advantage of modern smartphone capabilities, such as the built-in accelerometer and gyroscope for assessing gait, speed and postural stability during the TUG test (see Figure 2). The test modules also make the most of the precision and 24/7 availability of at-home digital technology. For instance, the digital finger-tapping test makes it easier to elicit and precisely characterize freezing of movement in a patient with PD (see Figure 3) compared with results obtained in a one-time test in clinic.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e7bf0b3b-709d-49e7-b812-8e82eb7fae00/20-NEU-1917435-CQD-Waiting-room-of-the-future-for-Special-Report_inset-2-805x358-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Illustration showing how the DVS app’s digital Timed Up and Go (TUG) test is administered. Although the subject here has a smart tablet strapped to his back, DVS app users can take the test by simply holding their smartphone in their hand.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4b192557-aec3-4d75-9c7f-e265c2aced87/20-NEU-1917435-CQD-Waiting-room-of-the-future-for-Special-Report_inset-3-805x389-1_jpg)

Figure 3. (A) Screenshot of the display from the finger-tapping test application on an iPhone. (B and C) Representative data from one participant performing the test with their less-affected hand (B) and more-affected hand (C). Each bar represents the time duration between the onset of consecutive taps (inter-tap interval), with the left target shown in red and the right target in green. Inter-tap intervals greater than 500 msec were classified as a freeze (blue line denotes threshold for a freeze). The more-affected hand performed fewer total taps compared with the less-affected hand (64 vs. 95, respectively), with a longer average inter-tap interval (461.6 vs. 315.1 msec, respectively), committed more errors (1 vs. 0, respectively), and exhibited more freezing episodes (11 vs. 0, respectively).

Advertisement

“The DVS app not only serves some of the basic functions of the physical exam,” says Dr. Alberts, “but it actually exceeds aspects of the physical exam by delivering highly objective, quantifiable data on symptoms that can be difficult to elicit clinically. And it’s automatically incorporating the findings into notes in the patient’s EHR.”

“These digital measures are superior to what we can measure manually, with the limitations of the human eye and the influence of subjective judgment,” adds Dr. Fernandez. “The app can precisely capture speed, hesitation, freezing and other characteristics of movement or decision-making that are of great interest in the evaluation of a patient with PD. It can help us understand a patient’s motor and cognitive function in a more nuanced way. For instance, the digital TUG test allows us to see how many right footsteps the patient took, or check their heel-toe stride, or check the number of freezing episodes. It’s all there. ”

Dr. Fernandez is quick to acknowledge that the DVS app doesn’t cover all aspects of the physical exam. “It doesn’t fully replicate an in-person examination, but it serves to augment virtual visits by introducing some cognitive and motor biomeasures that get incorporated into the note along with the patient-reported outcomes data from our existing platforms,” he says. “These can then help guide the discussion during the virtual visit, especially as trends in various measures accumulate over time.”

Dr. Alberts concurs. “The goal is to supplement the virtual visit and also potentially expand the reach of our virtual follow-up capabilities by allowing patients who live far from our facilities to go longer between in-person visits through introduction of these neuroperformance measures to the virtual visit,” he says.

Advertisement

He adds that while devoting a test module to reading comprehension may seem curious, pilot use of this module has proved quite valuable. “Reading comprehension is a proxy for healthcare literacy, which has been shown to predict risk for hospital readmission,” he explains. “Healthcare literacy is critical to understanding complex medication regimens and other matters affecting adherence. Understanding a patient’s healthcare literacy can help clinicians know how to interact with the patient and whether a family member needs to be enlisted for support.”

Collection of the patient-entered data elements of the waiting-room-of-the-future protocol has continued apace during the Neurological Institute’s sizeable shift toward virtual visits since the start of the pandemic. Meanwhile, the DVS app is poised for clinical introduction in fall 2020, first in Dr. Fernandez’s PD clinic and in the Center for Behavioral Health.

Notably, the test modules of the DVS app are similar to modules within the broader data-capture platforms utilized in the in-clinic setting — e.g., Cleveland Clinic’s Multiple Sclerosis Performance Test (MSPT), which was used in the proof-of-principle analysis cited above, as well as an adaptation of the MSPT customized for PD (“PD Optimize”) — to ensure continuity of monitoring. “This is critical, as the future of care for many patients will be a mix of in-person and virtual visits,” says Dr. Fernandez, “so we’ll need data tracking to continue seamlessly across the two settings.”

This element of data tracking — a foundational reason behind the waiting-room-of-the-future concept — promises to be at least as impactful for clinical research as it is for patient care, Dr. Fernandez notes. He explains that two of the primary needs in PD care — for effective therapies for PD-related dementia and gait instability — have gone unmet because of barriers that can be overcome with a clinical approach like the waiting room of the future. Chief among those barriers are the variability of PD patients’ presentation and clinical course and the crudeness of traditional PD assessment tools.

“The variability of PD has made it extremely labor-intensive and expensive to recruit large samples of appropriately similar patients to conduct the naturalistic studies needed to better understand the natural history of dementia and gait instability in PD,” Dr. Fernandez observes. “We need to systematically capture data on patients’ outcomes and performance measures as part of routine clinical care in order to achieve the scale of data necessary to really improve our understanding in these areas. Additionally, we need biomeasures that are far more sensitive, objective and convenient to obtain than crude traditional tools like the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, which is so effort-dependent on the part of the patient and subjective on the part of the clinician.”

He notes that the waiting-room-of-the-future approach — marked by routine, efficient collection of objective, quantifiable data for seamless inclusion in the EHR — addresses both barriers. “Beyond being hugely useful for individual patient care,” he says, “this approach can benefit research endeavors by accurately identifying which PD patients are most vulnerable, how they trend over time and how meaningful various tests are in those patients. Then, when a potential therapy is ready to be tested, we will know which patients are most appropriate candidates for it and which measures are best suited for its assessment. This could greatly accelerate progress in clinical research.”

While the DVS app extends the waiting room of the future into the virtual space, plans to expand and enhance the concept in the physical realm continue. One physical waiting room of the future already exists in Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis (depicted in this Consult QD article), and the similar space in the PD clinic will be opened as soon as pandemic-related conditions permit.

Meanwhile, a next-generation conception of the waiting room of the future will shape the design of a new Neurological Institute outpatient services tower to be built on Cleveland Clinic’s main campus. The design will be tailored to the unique challenges of patients with neurological conditions and will heavily leverage digital technologies.

“We envision incorporating various forms of passive monitoring of patients, where cameras with depth sensors can monitor things like gait or arm swing and transfer that data directly to the EHR,” Dr. Alberts says, noting that advance patient consent clearly would be required to activate the monitoring. “We’ve also started developing machine learning algorithms that could use passive monitoring to suggest a disease diagnosis based on detection of something like an asymmetric gait. The finding could be used to trigger clinical evaluation to enable earlier detection of neurologic dysfunction than what’s currently possible. We envision the new building as a site where novel technologies can be piloted for feedback and refinement.”

Advertisement

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Rapid innovation is shaping the deep brain stimulation landscape

Study shows short-term behavioral training can yield objective and subjective gains

How we’re efficiently educating patients and care partners about treatment goals, logistics, risks and benefits

An expert’s take on evolving challenges, treatments and responsibilities through early adulthood

Comorbidities and medical complexity underlie far more deaths than SUDEP does

Novel Cleveland Clinic project is fueled by a $1 million NIH grant

Tool helps patients understand when to ask for help