Online intensive program for headache, at-home neuroperformance testing and cognitive screens

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d9dd512d-3e87-4484-8a2d-781963c1dc72/older-couple-sitting-on-bed-1493008925)

Elderly couple

In the past few years, clinicians in Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute have blazed the trail for large-scale adoption of virtual visits across the spectrum of neurologic subspecialty care, as detailed in studies recapped here. While their adoption of teleneurology has been further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps more remarkable are some distinctive additional forays into at-home patient management pioneered out of the Neurological Institute.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This article profiles three such initiatives: (1) an intensive interdisciplinary program for chronic headache offered through a well-designed series of virtual visits, (2) a smartphone app that replicates a few key aspects of the physical neurologic examination and (3) a brief online cognitive assessment tool that goes beyond standard dementia screening.

Successful management of chronic headache typically requires a multipronged approach drawing on targeted therapies and lifestyle modifications. Traditionally, for many patients that has meant committing to an intensive interdisciplinary outpatient program with daily in-person sessions over two to three weeks.

“This is an effective approach for chronic migraine, but many patients cannot make that type of in-person commitment because of restrictions related to their job, travel or finances,” says Emad Estemalik, MD, Section Head of Headache and Facial Pain in the Neurological Institute’s Center for Neurological Restoration.

To better meet these patients’ needs, a few years ago Dr. Estemalik and colleagues began adapting components of Cleveland Clinic’s long-standing in-person intensive outpatient program for chronic headache, known as IMATCH, into an all-online version called vMATCH (Virtual Method for Assessment and Treatment of Chronic Headache).

The interdisciplinary approach mixes educational components and individual counseling over a series of hourlong sessions conducted as MyChart® video visits using Zoom™ for Telehealth, a HIPAA-compliant service integrated with Cleveland Clinic’s electronic health record (EHR) and MyChart online health management platform for patients.

Advertisement

Series of virtual visits goes where one-off visits can’t. Sessions cover migraine and headache pathophysiology, treatment options, diet, sleep hygiene, stress management, relaxation, mindfulness and other aspects of wellness. Each session is led by a program coach — an advanced practice provider who interacts with the patient face-to-face online and helps individualize session content. Educational materials are provided via MyChart, and homework — such as keeping a headache diary and practicing relaxation exercises — is assigned and discussed.

The standard vMATCH series consists of eight sessions that are held about once a week, but the number and focus of sessions can be customized to the patient’s needs and preferences.

“The efforts and education required for a patient with chronic migraine to get better exceed what physicians can typically provide in an office visit,” explains Dr. Estemalik. “This online program gives us the time to educate patients and tailor strategies to their individual needs.”

“vMATCH provides a perfect venue for fine-tuning management,” says Jena Gustafson, PA-C, lead program coach for the sessions. “Talking to the patient for an hour every week or so gives me the opportunity to offer new solutions and quickly learn whether they helped.”

In general, she and her fellow program coach can adjust medications and treatment strategies as needed. For issues that require physician input, they consult with one of the headache neurologists on staff and get back to the patient.

Advertisement

Swift expansion, ongoing outcomes study. Since its launch in mid-2018, vMATCH has seen demand and volume grow, and the in-person IMATCH intensive program has since been phased out. While patients were initially billed for vMATCH sessions out of pocket, sessions are now billed to insurance.

Gustafson notes that the program is also meeting the needs of patients beyond those with chronic headache. “We’ve found that vMATCH provides an excellent educational groundwork for patients newly diagnosed with migraine who want to learn more about how to manage their chronic condition,” she says.

The team is now conducting a grant-funded cross-sectional study to compare outcomes between vMATCH participants and patients receiving traditional chronic headache care. Outcomes including patient satisfaction, measures of overall function, and depression and anxiety scores are being assessed at three-month intervals through at least a year after program completion.

Dr. Estemalik is unaware of other programs of this type in the U.S. He says that adapting the former in-person intensive chronic headache program to the vMATCH format involved about eight months of planning.

“vMATCH is the continuation of our philosophy that patients with chronic headache fare best when you integrate multiple aspects of management,” he concludes. “It is simply doing so in a way that is much more flexible for patients, more efficient and more affordable.”

While the Neurological Institute’s extensive experience with virtual visits revealed many benefits of teleneurology, it also made clear one significant shortcoming: Certain elements of the physical examination that were missing from virtual visits could often be very important to optimal delivery of neurologic care.

Advertisement

That prompted biomedical engineer Jay Alberts, PhD, Vice Chair of Innovation in the Neurological Institute, to lead an effort to bring key aspects of the physical exam to the virtual care setting. Dr. Alberts had partnered with clinicians to develop several well-established Cleveland Clinic data-capture platforms for the in-clinic setting, such as the Multiple Sclerosis Performance Test (MSPT) and its adaptation for patients with Parkinson disease, PD Optimize. In addition to offering questionnaires assessing subjective metrics and outcomes, these digital tools enable patients to complete objective neuroperformance tests via iPads, with immediate data transfer to the EHR to inform patient care (and to a cloud database for population-level research).

Clinical use of the MSPT was validated in a proof-of-principle analysis published in 2019, so a natural next step was to start translating it and similar Cleveland Clinic tools for use in a setting where patients were increasingly being seen — online at home. “The future of care for many patients will be a mix of in-person and virtual visits,” says Dr. Alberts. “So we need to be able to monitor patients’ subjective and objective metrics in and between both settings.”

The obvious vehicle for at-home neuroperformance measures was a smartphone application, so work began on the Digital Neurological Vital Signs app, or DVS (“Digital Vital Signs) app for short.

DVS app essentials. The app was developed by Cleveland Clinic researchers, clinicians and engineers to quantify a number of highly meaningful neurologic functions (“vital signs”) that replicate portions of a standard physical exam. The app is downloaded by the patient for self-administration and is designed to collect objective, quantitative data to characterize cognitive and motor functioning in four domains:

Advertisement

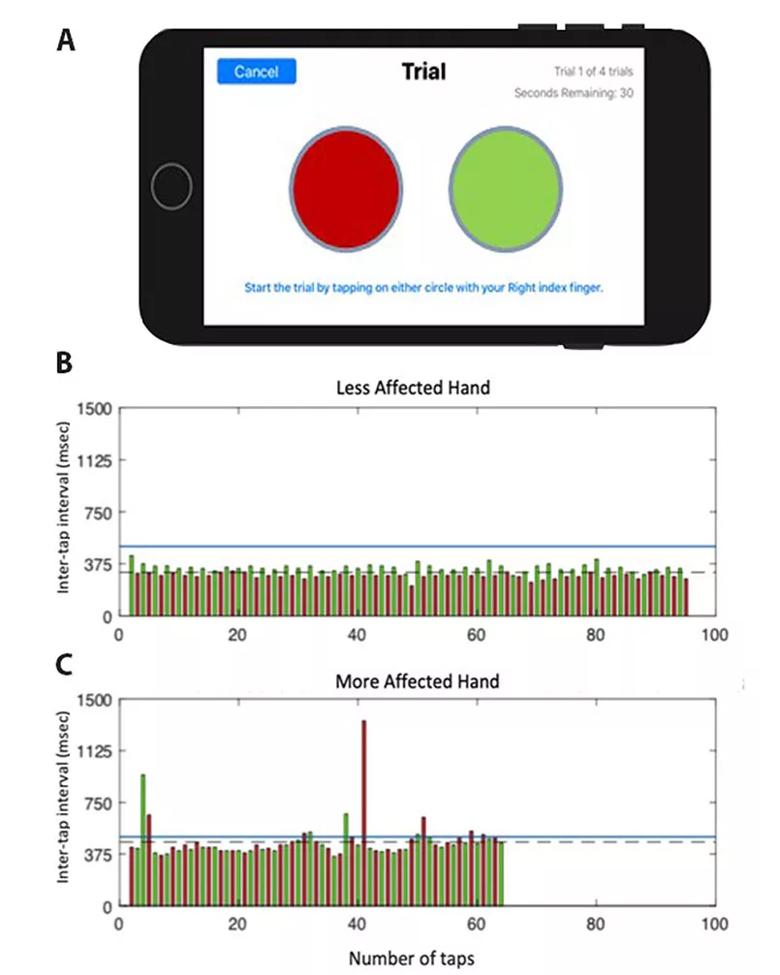

Each test module takes advantage of modern smartphone capabilities, such as the built-in accelerometer and gyroscope for assessing gait, speed and postural stability during the TUG test. The test modules also make the most of the precision and 24/7 availability of at-home digital technology. For example, the digital finger-tapping test makes it easier to elicit and precisely characterize freezing of movement in a patient with Parkinson disease (see Figure) compared with results obtained in a one-time test in clinic.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c15c297e-ed01-4d9e-9e8a-3b562d99ae45/20-NEU-1917434-CQD_inset-805x1006-1_jpg)

Figure. (A) Screenshot of the display from the finger-tapping test application on an iPhone. (B and C) Representative data from one participant performing the test with their less-affected hand (B) and more-affected hand (C). Each bar represents the time duration between the onset of consecutive taps (inter-tap interval), with the left target shown in red and the right target in green. Inter-tap intervals greater than 500 msec were classified as a freeze (blue line denotes threshold for a freeze). The more-affected hand performed fewer total taps compared with the less-affected hand (64 vs. 95, respectively), with a longer average inter-tap interval (461.6 vs. 315.1 msec, respectively), committed more errors (1 vs. 0, respectively) and exhibited more freezing episodes (11 vs. 0, respectively).

“The DVS app not only serves some of the basic functions of the physical exam,” says Dr. Alberts, “but it actually exceeds aspects of the physical exam by delivering highly objective, quantifiable data on symptoms that can be difficult to elicit clinically. It also is more precise and comprehensive in its measurements than the manual assessments that can be done in person. And all data are automatically incorporated into notes in the patient’s EHR.”

All about augmenting the virtual visit. Dr. Alberts acknowledges that the app doesn’t fully replicate an in-person examination. “The goal is to supplement and augment the virtual visit,” he says. “It also may expand the reach of our virtual follow-up capabilities by allowing patients who live far from our facilities to go longer between in-person visits through introduction of neuroperformance measures to the virtual visit.”

Reading comprehension was included in the app as a proxy for healthcare literacy. “Healthcare literacy has been shown to predict risk for hospital readmission and is critical to understanding complex medication regimens and other adherence-related issues,” Dr. Alberts explains. “Knowing a patient’s healthcare literacy can help clinicians know how to interact with the patient and whether a family member needs to be enlisted for support.”

While development of the DVS app started well before the advent of COVID-19, the pandemic has accelerated it. Clinical introduction of the app is on pace to begin in fall 2020, starting with Parkinson disease patients in the Center for Neurological Restoration and patients in the Center for Behavioral Health. (For more on the DVS app, see this related Consult QD article.)

Several years ago, Cleveland Clinic neuropsychologists Darlene Floden, PhD and Robyn Busch, PhD, set out to solve a major clinical workflow problem for the Neurological Institute: how do you quickly and accurately screen every adult neurology patient for any type of cognitive problem without increasing provider workload? Available cognitive screening tools are designed to detect dementia in older adults, and they are generally paper-and-pencil tests that require provider time to administer and score.

“The Neurological Institute sees a huge population of younger adults who may have cognitive problems related to their neurologic condition but whose problems aren’t detected by dementia screening tools,” says Dr. Floden. “At the same time, patients may be concerned about their cognition but there isn’t sufficient time to explore this in a clinic visit that must address other pressing symptoms, and referral for a three-hour specialty cognitive assessment seems like overkill. We wanted to give providers another option to help with clinical decision-making.”

Enter the BACH. The two neuropsychologists wanted to create a screening tool that was considerably more challenging than dementia screening tools and therefore more sensitive to milder cognitive problems that can be seen at any age. In addition, it had to be self-administered with real-time results going directly to the provider, so that it was a help, rather than a hindrance, to provider workflow.

Using cognitive neuroscience procedures, they developed a computerized assessment and questionnaire that is self-administered on an iPad. They conducted extensive normative testing in over 1,000 individuals to find the shortest, most accurate version to use for a wide range of ages and cognitive abilities. The resulting test, dubbed the Brief Assessment of Cognitive Health (BACH), can be completed independently in a clinic waiting room in 15 minutes and provides several key pieces of information.

First is the probability, expressed as a percentage, that the individual has some sort of cognitive problem. This probability is then supplemented by screening metrics for three common factors that could contribute to a high probability of a cognitive problem:

Because the BACH is linked to the Epic medical record, findings from the BACH are immediately available to the patient’s treating physician for review.

“The BACH is designed to be a decision-making aid, not to diagnose a particular cognitive problem or specify it as, say, a memory deficit or a problem with executive function,” notes Dr. Floden. “You can’t expect a multipurpose tool to fully characterize specific cognitive profiles in 15 minutes.”

Its purpose instead is to flag the presence of a likely cognitive problem so the treating clinician can consider referral for additional testing as appropriate. Or, if the BACH detects likely depression or a sleep problem or stress issues, the clinician can treat those issues first and see if the patient’s cognition improves. If the provider would like additional testing to better characterize a cognitive problem, the neuropsychology service can provide these patients with an express appointment or a comprehensive evaluation, as the provider feels necessary.

BACH use cases. Patients take the BACH at the discretion of treating physicians. A common scenario might involve a patient in his or her 40s who expresses concern about his or her own recent memory issues after a parent has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. “The BACH would be a great tool to screen for problems before referring for a lengthy neuropsychological evaluation,” says Dr. Busch. If the patient scores well, the neurologist has objective data to allay fears during the visit. In other situations, the BACH may be ordered because the provider has reason to suspect an underlying cognitive issue that merits evaluation. An example might be a 58-year-old patient who returns for follow-up and does not seem to recall important information relayed during the prior clinic visit.

Other, more automated models for deployment of the BACH have also been implemented. For example, the BACH can be added to the order set for specific subsets of patients with a high probability of cognitive impairment. “Roughly half of patients who present with new-onset seizures have cognitive difficulties, which may be mild and go unidentified,” says Dr. Busch, whose primary appointment is in Cleveland Clinic’s Epilepsy Center. “It can be difficult to identify such problems during a routine clinical visit focused primarily on getting the seizures under control. We have implemented the BACH in our Epilepsy Center so physicians can quickly identify those new-onset seizure patients who may benefit from more comprehensive neuropsychological testing or to screen cognition in their established patients with cognitive complaints.”

Current state and next steps, including at-home administration. The BACH has been implemented by the Neurological Institute’s Epilepsy Center and Cerebrovascular Center, with more centers set to follow soon. It’s also being used by the Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center, and there is considerable interest from other specialties as well. “The BACH is built to apply to patients with virtually any chronic disease,” says Dr. Floden. “It’s a quick and easy tool that is useful for spotting cognitive issues that might interfere with patients’ capacity for things like adhering to postsurgical instructions and following complex medication regimens, regardless of the underlying condition.”

The goal is to make the BACH available for use throughout Cleveland Clinic and to external providers as well. But a few refinements are planned first, including near-term technical adjustments to allow patients to take the BACH at home. “At home-administration will be very helpful, especially with the increased use of virtual visits,” notes Dr. Busch. “It’s aligned with our overarching goal of more actively and efficiently assessing for cognitive problems in the context of neurological disorders.”

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges