Teen with uveitis, glaucoma, cataract illustrates value

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A teenager with uveitis.

A teenager with active uveitis treated with steroids.

A teenager with active uveitis treated with steroids who develops glaucoma.

A teenage with active uveitis treated with steroids with glaucoma treated surgically with a tube, with a cataract.

A teenage with active uveitis treated with steroids, glaucoma with a tube and now pseudophakic who can only see counting fingers

This is the nightmare scenario for any ophthalmologist. Not only do we want to improve our patient’s vision, we want our interventions to not lead to worse outcomes. In these complicated cases, where it seems every treatment choice is followed by yet another setback, sometimes it is best to take a step back and re-evaluate the plan.

The patient is a teenage girl who presented to me after one year of declining vision. Diagnosed with idiopathic uveitis in one eye, she had been treated with topical steroid therapy without much success. In order to get control of her disease, local steroid injections were required. Unfortunately, the combination of active uveitis and steroids lead to elevated IOP. She required placement of a glaucoma tube in order to control her pressure. Her vision continued to decline and then she developed a cataract. The hope was that her vision would improve immediately after her cataract surgery.

She presented to the Cole Eye Institute one week after that surgery, performed elsewhere, with counting fingers vision and symptoms of a dark spot in her central vision, fearful about the possibility that her vision would not return.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0c00cc09-1f53-41e4-8b4e-cf615b134403/18-EYE-4338-Srivistava-CQD-Fig-1_jpg)

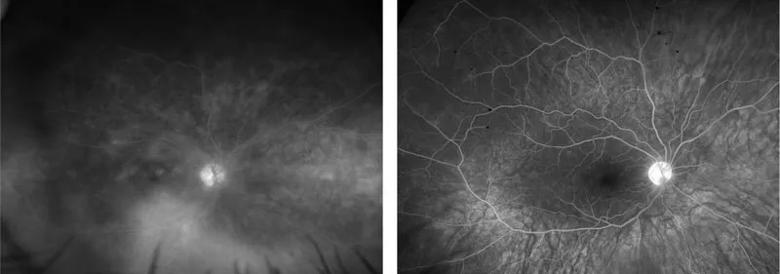

Initial fluorescein angiogram (left) with diffuse retinal vascular leakage indicates activity. Fluorescein angiogram 1 year later (right) shows significant improvement in leakage after immunosuppression

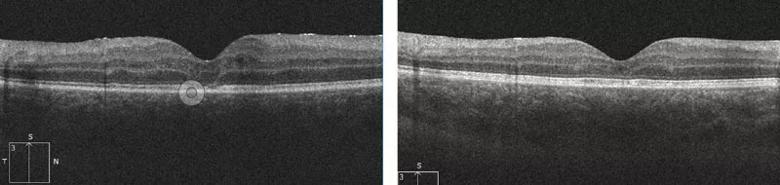

Her examination and imaging began to give us more of the story. Wide field fluorescein angiography showed evidence of diffuse retinal vascular leakage in her right eye. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed mild cystic changes, but more worrisome was outer retinal loss indicating chronic damage to her retina. Although her anterior chamber and vitreous did not reveal much cellular activity, the presence of the diffuse leakage and outer retinal loss on OCT told me her eye was severely inflamed, and had been for quite some time. It was time to have a discussion with the patient and her family about the need to adjust her immunosuppressive therapy.

Immunosuppression can be a scary topic for patients, especially for young people. Despite the excellent data on the safety and efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for patients like ours, it does take buy-in from the patient and family in order to treat this disease effectively. At the Cole Eye Institute, we often will manage our patients in conjunction with an adult or pediatric rheumatologist, very commonly with same day appointments.

For this case, my pediatric rheumatology colleague Andrew Zeft, MD, immediately completed a work up and adjusted her therapy to methotrexate and adalimumab. We decided to start her on oral steroids as well, to get her eye under control quickly. Since she already had a tube in place and was pseudophakic, there was a short discussion on using local therapy, but given the severity of disease at onset, I decided to start with oral medication first.

Advertisement

The patient returned in two weeks with some improvement – she was 20/400. Small win in the world of retina and uveitis! With time, we began to see other developments, including reduction in leakage and improvement in foveal contour. A few months later, no leakage was visible on FA and her outer retina began to look normal. Twelve months after her initial presentation, the patient returned with 20/60 vision. She and her parents were ecstatic, as were we.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/87956be8-294e-4c57-8637-ec9fd982dcc2/18-EYE-4338-Srivistava-CQD-Fig-2_jpg)

Optical coherence tomography of patient’s right eye at presentation (left image) indicates loss of ellipsoid zone (yellow arrow). At right, normalization of outer retinal anatomy is seen 12 months later.

Just when you think things are going well, you are reminded how challenging chronic diseases can be. The hardest thing about immunosuppression is that it is chronic and sometimes it is difficult for some patients to adhere to, even when things are going well. So it was not a big surprise when six months later, this patient presented with worsening vision.

Her macular edema had returned. The EMR showed that her medication was unchanged, but my nurse, Kim, picked up the truth – the patient does not like adalimumab injections, so she has been skipping some.

After some encouragement and discussion about whether to choose a different medication, she agrees to give it another try. Upon return one month later her vision is back to 20/60. We have come a long way, but we know that she will need continued coordinated care for many years.

We come up with a plan, adjust some medications and plan to check on her progress soon.

Advertisement

We hope for the best but know it’s a long road ahead.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A review of pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment options

How computational tools and personalized biomechanics can improve keratoconus detection, ectasia risk assessment and surgical outcomes

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists