Study reveals more about the pathophysiology of Salzmann’s nodular degeneration

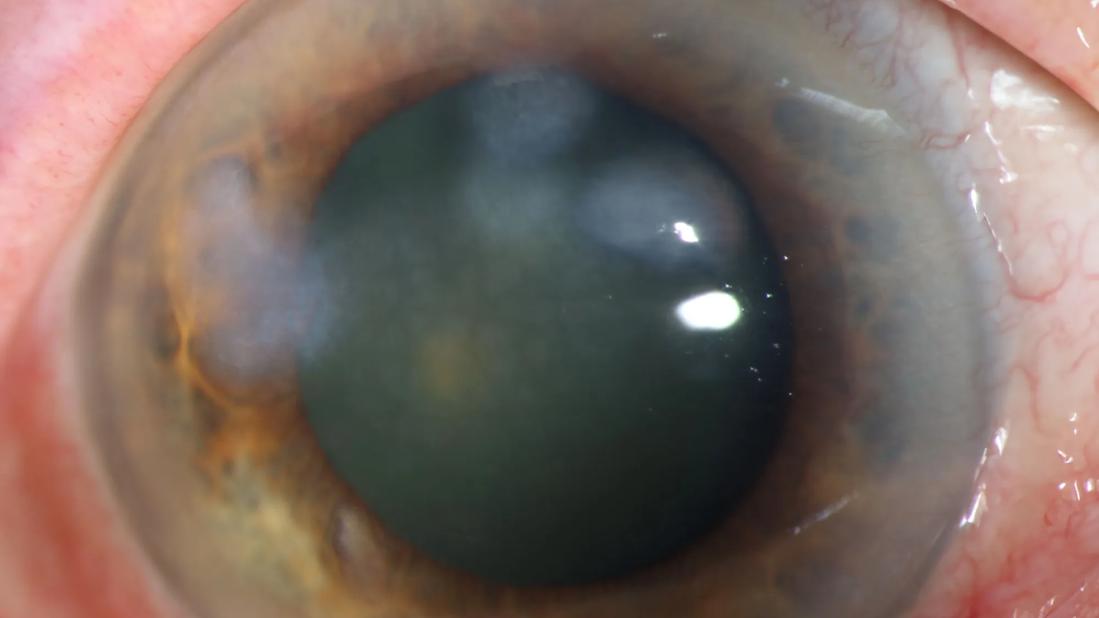

Salzmann’s nodular degeneration (SND) is a common, indolent condition in which fibrous nodules form on the cornea. When the nodules begin to affect a patient’s vision, ophthalmologists can scrape off the tissue with a scalpel to restore the cornea’s smooth surface.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Most ophthalmologists frequently perform this procedure,” says Steven E. Wilson, MD, Director of Corneal Research at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. “You don’t even need a laser. Usually, you just use a scalpel to scrape off the nodules in one piece. It’s as easy as removing the peel of an orange.”

At least, that’s the usual experience. Other times, the scarring fibrosis isn’t encapsulated in an easy-to-peel nodule. It spreads into deeper layers of the cornea, where it can’t be removed with simple scraping.

A recent study by Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute reveals more about the pathophysiology of SND and offers one explanation for why some cases are more challenging to treat.

According to earlier studies, Salzmann’s nodules are formed of myofibroblasts and the disordered extracellular matrix these cells produce. These corneal nodules are located between the epithelial basement membrane and Bowman’s layer, the most anterior layers of the cornea. This is noteworthy, says Dr. Wilson, because normally there isn’t a real space between those two layers.

“We think that people with SND had an earlier injury to the cornea — maybe a surgery, trauma or infection — that damaged the epithelial basement membrane,” he says. “Because of that damage, fibrocytes in tear film or corneal fibroblasts entered the space where there normally are no cells. Over time, those cells started proliferating thanks to transforming growth factor beta from the epithelium and tear film. They may have grown slowly, but eventually progressed into a collection of myofibroblasts and fibrous tissue that began to extend over the pupil, causing vision problems.”

Advertisement

This process can take years, he surmises, which is why patients may not present with SND until decades after refractive surgery or other corneal insults, including ones they may have forgotten they had.

“Our article postulates that all patients with SND had past corneal trauma of some kind that damaged the epithelial basement membrane,” Dr. Wilson says.

That may explain the typical cases of SND, which are easily removed with scraping.

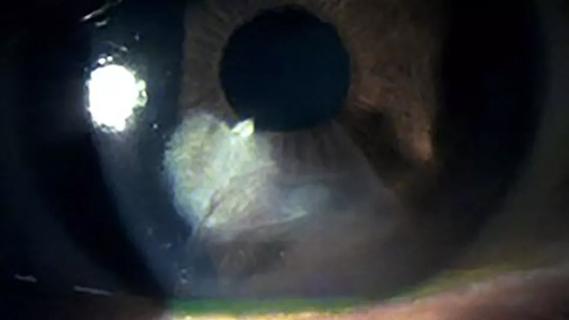

“However, if the patient had a previous surgery like LASIK, involving an incision through Bowman’s layer, the fibrosis can extend down the incision,” he adds.

When the fibrosis isn’t confined but spreads deeper into the cornea’s anterior stroma, it is more difficult to remove.

“SND really should be called Salzmann’s subepithelial fibrosis,” Dr. Wilson says. “That’s a more accurate description. It’s fibrosis that can spread in all directions.”

In their study, published in the Journal of Refractive Surgery, Dr. Wilson and corneal surgeon William J. Dupps Jr., MD, PhD, reviewed three atypical cases of SND treated at the Cole Eye Institute. All three patients had a history of surgery in the eye: Two patients had a history of LASIK, and one had a history of photorefractive keratectomy (PRK).

“In the patients with LASIK, I was able to remove enough of the nodules to improve their vision, but there was fibrosis deeper in the cornea, along the flap margins, which would have required more aggressive action to remove,” Dr. Dupps says. “We will watch these patients over time to see if the nodules regrow and require further treatment.”

Advertisement

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can help distinguish between nodules that will easily scrape or peel off and those that won’t, he notes. While OCT of the patient with PRK showed that the fibrosis had not spread beyond Bowman’s layer, the OCT of the patients with LASIK showed the opposite, explaining why their treatment was more challenging.

“Usually, the fibrosis stops at the subepithelial space. Those nodules are easy to remove,” Dr. Dupps says. “But, if there isn’t a sharp delineation there and if the opacity of the nodule appears feathery, that indicates that the fibrosis extends into the cornea. Those nodules will be more surgically significant.”

The occurrence of deep Salzmann’s extension after LASIK appears to be more common after LASIK performed with a microkeratome rather than a femtosecond laser. No cases of SND have been reported in over 15,000 LASIK cases performed at the Cole Eye Institute since 2003, note the authors.

For nodules that extend deep into the cornea, Drs. Wilson and Dupps advise trimming off the portion of the nodule that’s causing irregularity of the corneal surface.

“Get the surface as smooth as you can, knowing that you may have to leave the fibrosis that extends down the incision,” Dr. Wilson says. “Trying to remove the rest may cause more damage.”

In those cases, follow the patient. If vision problems recur due to regrowth of the nodule, consider more extensive surgery, such as lamellar keratoplasty.

For patients that are not candidates for surgery, Dr. Wilson hypothesizes that topical losartan can kill myofibroblasts and halt the progression of SND. However, it likely will not remove the opacity already present. Typically there are no corneal fibroblasts in the subepithelial space to remove the disordered extracellular matrix produced by myofibroblasts, as occurs in the deeper stroma.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Studies continue to indicate effectiveness and safety

Identifies weak spots in the cornea before shape change occurs

Novel use of tPA reduces fibrin response in the eye

Researcher gives guidance for clinical trials

Untreated seropositive erosive RA led to peripheral ulcerative keratitis

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence