Device features, desensitization strategies can help

By Colleen Lance, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

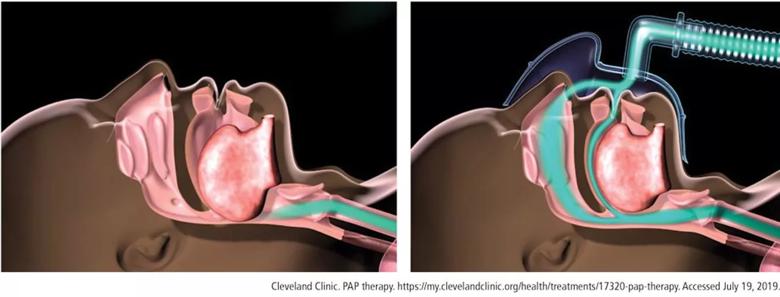

Positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy is used to open an obstructed upper airway (Figure 1). PAP therapy consists of a small bedside unit that creates a pressurized column of air that is delivered through tubing to a facial interface, which can be nasal, oral or both. Collin Sullivan, MD, created the nasal continuous PAP (CPAP) in 1982, using parts of a vacuum cleaner to create positive pressure that successfully resolved hypoxemia in a patient.1 Today, the various forms of PAP therapy include CPAP, the most common, auto-PAP (APAP) and bilevel PAP (BiPAP).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e7cf03dc-15f8-4a79-987d-13656ba8f7e7/Positive-Airway-Pressure-F1_large__jpg)

Figure 1. Obstructed airway (left) is opened with a column of air delivered using positive airway pressure therapy (right).

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine practice guidelines for PAP are based on 342 articles, most rated as evidence levels I and II, concluding that CPAP is superior to conservative treatment to:

These practice parameters are based on evidence of improved daytime sleepiness and reduced incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treated with PAP. The evidence is less clear for neurocognitive markers and cardiovascular events in the treatment of patients with mild sleep apnea.

Sleepiness

A study evaluated sleepiness outcomes in 149 patients with severe sleep apnea with an average apnea–hypopnea index of 69 relative to the duration of nightly CPAP use. Sleepiness was measured using the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Scale and Multiple Sleep Latency Test. Results suggest that a greater percentage of patients had improved daytime sleepiness as the total hours of sleep using CPAP increased.3

Advertisement

The Apnea Positive Pressure Long-term Efficacy Study (APPLES) was a six-month, multicenter, randomized study of neurocognitive function in patients with OSA (N = 1,098).4 Subjective sleepiness as measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale showed statistically significant improvement at two and six months for patients with moderate to severe OSA using CPAP. Objective sleepiness as measured by the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test showed statistically significant improvement (i.e., improved daytime alertness) at two and six months for patients with severe OSA using CPAP.

Neurocognitive function

APPLES also tested for attention and psycho motor function as well as verbal learning and memory, though no statistically significant improvements were found in these parameters.4 Executive function and frontal lobe function showed transient improvement at two months in patients with severe sleep apnea using CPAP, but the improvement was not statistically significant at six months.

Cardiovascular outcomes

Hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Use of CPAP therapy reduces blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. A study of 32 patients who had a baseline polysomnography with 19 hours of continuous mean arterial blood pressure monitoring were treated with therapeutic CPAP (n = 16) or subtherapeutic CPAP (n = 16).5 Therapeutic treatment with CPAP for patients with moderate to severe OSA resulted in statistically significant reductions in mean arterial pressure for both systolic and diastolic pressures. The blood pressure reductions achieved are estimated to reduce coronary artery diseases by 37% and stroke by 56%.5

Advertisement

The risk of cardiovascular events in men with severe sleep apnea is high but mitigated by the use of CPAP. In a cohort of 1,651 men, untreated severe sleep apnea resulted in a threefold increase in the rate of cardiovascular events per 1,000 patient-years compared with four other groups: a control group, men who snore, men with untreated mild to moderate sleep apnea, and men with OSA using CPAP.6 However, when men with severe sleep apnea use CPAP, the risk of cardiovascular events is reduced to the rate in men who snore.

Atrial fibrillation. In patients with atrial fibrillation treated with direct-current cardioversion defibrillation, the recurrence of atrial fibrillation at 12 months was greater in patients with untreated OSA (82%) compared with a control group (53%) and patients treated for OSA (42%).7

Heart failure. In a study of 24 patients with heart failure, an ejection fraction less than 45% and OSA, patients were randomized to a control group for medical treatment or medical treatment and nasal CPAP for one month.8 In the CPAP group, mean systolic blood pressure and heart rate were reduced, resulting in an improved ejection fraction compared with baseline as well as compared with patients in the control group.

In patients with heart failure (N = 66) with and without Cheyne-Stokes respirations in central sleep apnea, patients treated with CPAP were found to have a 60% relative risk reduction in mortality-cardiac transplant rate compared with the control group not using CPAP.9 Further stratification in this study showed that patients with significant Cheyne-Stokes respirations and central sleep apnea had an improved ejection fraction at three months and an 81% reduced mortality-cardiac transplant rate.9

Advertisement

Adherence to PAP therapy is a problem in terms of both frequency of use and duration of use per night. A review of randomized control trials of CPAP compliance between 2011 and 2015 found adherence varied widely from 35% to 87%.10 The average hours of PAP use per night was found to be five hours in APPLES.4 Patients adherent to PAP therapy at one month remained adherent at one year, suggesting patients using CPAP for one month were more likely to continue use at one year.10 Impediments to PAP use typically involve the facial interface discomfort, lack of humidity and pressure intolerance.

Today’s PAP devices have features designed to make them easier to use and more comfortable to improve adherence to therapy. Facial interface options, heated humidifiers, tubing accessories, cleaning devices, reporting of compliance data via telecommunication and pressure adjustment features of PAP devices may improve patient adherence and comfort, as highlighted in the case scenarios below.

Interfaces

Case scenario #1. A 32-year-old woman with moderate sleep apnea complains that her PAP nasal mask is making very loud noises and is disturbing her bed partner. She is a side sleeper and also reports that she wakes with an extremely dry mouth.

Management of the leak could include which of the following?

Answer: All of the above.

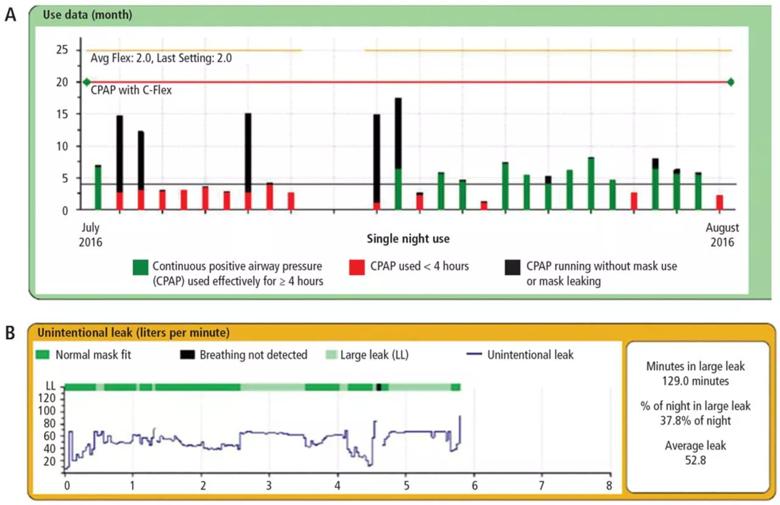

Figure 2 shows an overview of data from the patient’s machine for the past month and one night of leak data.

Advertisement

Both the month-use data and single-night leak data show mask leakage.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/01f8d124-8070-4aad-aa4a-8b96807247c3/Positive-Airway-Pressure-F2_large__jpg)

Figure 2. Download of positive airway pressure use data for a month (A) and leak data for a night (B).

There are many types of PAP interfaces, such as nasal masks, nasal pillows, nasal cushions, full-face masks and less frequently used oral and total face masks. The mask interface is a common impediment to use of PAP therapy, often due to poor mask fit or leakage.

Nasal masks cover only the nose and require that the mouth remains closed, which can be achieved with the addition of a chin strap. Nasal masks are available in a variety of materials including cloth. Nasal pillows actually go into the nostrils whereas the nasal mask is positioned under the nose. A nasal cushion mask sits under the nose but does not go into the nostrils.

A study by Lanza and colleagues11 evaluated patient comfort with PAP therapy based on the type of nasal interface mask. Patients using nasal pillows had improvement with respect to swollen eyes, discomfort, skin breakdown and marks on the face compared with patients using nasal masks; however, nasal pillows can cause nostril pain.

Several types of full-face masks are available, some that fit over the bridge of the nose and some that fit just under the nose. A variety of head straps are available to secure full-face masks. One benefit of full-face masks is that air pressure is delivered to both the nose and the mouth, so the mouth can be open or closed. However, the larger surface area of the full-face mask increases the potential for leaks. A study of adherence in 20 patients using CPAP with nasal masks or full-face masks evaluated hours per use, adherence at 12 months and comfort.12 Patients using full-face masks had more hours per use, better adherence at 12 months and more comfort than patients using nasal masks.

Interface skin irritation and leak management. To help combat skin irritation, particularly for patients with rosacea, cloth products are available for use beneath the mask and headgear. Silicone pads for masks that cause pressure on the bridge of the nose can help protect against skin breakdown. Sleeping positions other than the supine position can contribute to mask leak. CPAP pillows are designed to allow patients to sleep in their desired position while maintaining an adequate mask seal. The pillows are shaped or have cutouts that prevent the mask from pushing on the pillow and creating a leak.

Humidification

Case scenario #2. A 54-year-old man with severe sleep apnea recently initiated CPAP therapy. He quickly discontinued use due to nasal congestion.

Which of the following is NOT recommended?

Answer: Use of short-acting nasal decongestants.

Nasal congestion is a common reason for nonadherence to CPAP therapy.13 Pressurized air is very drying and can be very uncomfortable. Residual apneic events can even precipitate further congestion. The use of humidification with CPAP can improve patient comfort and compliance. The vast majority of patients use CPAP devices with heated humidifiers. Heated humidification has been found to increase CPAP use and improve daytime sleepiness and feelings of satisfaction and being refreshed compared with cold humidity or no humidity.14 Cold humidification improved daytime sleepiness and satisfaction, but not to the degree found with heated humidification.

Heated humidifiers are incorporated in the CPAP machine or attach to it. Heated in-line tubing helps with “rain out,” which refers to water condensation inside the tubing and mask associated with CPAP humidification.

Topical decongestants can actually worsen congestion and cause a reflex vasodilation. Topical nasal steroids can be used for nasal congestion and may be beneficial.

Tubing

The tubing from the PAP device to the facial interface can be a source of irritation to patients due to rubbing against the skin or entanglement. Products to cover the tubing to reduce irritation and avoid entanglement are available. Extra-long tubing is also available.

Cleaning

Some people find cleaning CPAP equipment daunting. Cleaning devices are available and recommended to patients looking for reassurance about how to keep their CPAP equipment clean. There are also CPAP wipes to clean the mask of oils and creams from the skin to improve the mask seal and reduce leaks.

Pressure control

Advanced modalities are available to adjust how pressure is delivered by PAP devices, including ramp, APAP, pressure relief and BiPAP. Ramp is a feature that delivers a lower pressure at the beginning of the sleep cycle and slowly increases pressure to therapeutic levels. The lower pressure makes it easier for the user to fall asleep and builds to therapeutic pressure once asleep. APAP adjusts the pressure automatically when needed and reduces the pressure when not needed. Pressure relief is a feature that allows the PAP pressure to decrease at the point of expiration. BiPAP gives a distinct pressure on inspiration and a distinctively different and lower pressure at the point of expiration.

Case scenario #3. A 52-year-old woman with hypertension and mild sleep apnea has a polysomnogram with an apnea–hypopnea index of seven events per hour that increase to 32 events per hour in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. She is on CPAP at 5 cm of water, but complains of waking every two hours with a sense of panic and hot flashes.

Which of the following is the most likely cause of her symptoms?

Answer: While all of these choices can occur, the most likely cause is undertreated REM-related apnea.

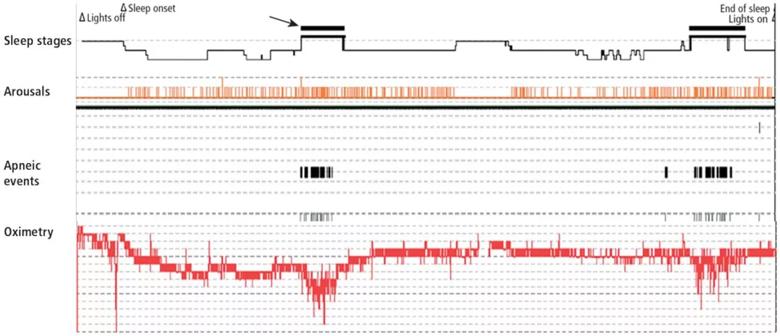

The sleep study overview for this patient is shown in Figure 3. During REM sleep, arousals and apneas are clustered and associated with a severe drop in oxygen levels. While doing well on CPAP at 5 cm of water, when the patient dreams, the apnea may become worse and more pressure may be needed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d44fed7d-0986-44e8-85b6-c2d68f4e3b56/Positive-Airway-Pressure-F3_large__jpg)

Figure 3. Sleep study overview showing rapid eye movement sleep (arrow/black bar) associated with increased arousals and apneic events and decreased oxygen levels.

What would be the best next step in treatment for this patient?

Answer: APAP.

APAP incorporates an algorithm that detects and adjusts to airflow, pressure fluctuations and airway resistance. The consensus from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine is that APAP is useful in the case of:

Case scenario #4. A 45-year-old man with severe sleep apnea uses CPAP at 10 cm of water. He complains of the inability to exhale against the pressure from the device.

What would be the best next step?

Answer: Set the pressure relief to a maximum of 3.

The CPAP device delivers pressure in conjunction with the patient’s inspiration and expiration. At the point of expiration, there is a decrease in the pressure delivered by the device to make it easier for the user to exhale. Three selectable settings provide flow-based pressure relief with a setting of 1 for the least degree of pressure reduction and a setting of 3 for the greatest degree of pressure reduction.16

In a study of the effect of PAP with pressure relief, 93 patients were assigned to use APAP without pressure relief, CPAP with pressure relief (C-Flex) or APAP with pressure relief (A-Flex).16 At three and six months, patients using A-Flex had the best adherence to therapy.

Quality of life was also examined in this study.16 For patients using APAP alone, there was no statistically significant difference in the Epworth Sleepiness Scale measuring daytime sleepiness or the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. However, in patients using A-Flex, daytime sleepiness improved, as did sleep quality, with statistically significant improvement at three months.

Case scenario #5. A 62-year-old man with severe sleep apnea uses CPAP set at 17 cm of water and pressure relief set at 3. He stopped using CPAP due to abdominal pain, extreme belching and pressure intolerance.

What would be the appropriate next step?

Answer: All of the above.

BiPAP devices provide two distinct pressures, one for inhalation and one for exhalation. BiPAP also has the ability to deliver a higher overall pressure. A CPAP device typically has a maximum pressure of 20 cm of water, but BiPAP has a maximum pressure of 25 cm of water on inspiration. BiPAP may be helpful in patients with air aphasia and extreme belching. If a patient cannot tolerate CPAP because of the pressure, and if C-Flex has not alleviated the problem, BiPAP would be the next step.

The effectiveness and level of comfort of BiPAP compared with CPAP for the treatment of OSA was evaluated by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.2 The analysis of seven randomized control trials reporting level I and II evidence found that BiPAP was as effective as CPAP in the treatment of OSA in patients with no comorbidities. For patients with OSA and comorbidities, a level III evidence study reported an increased level of comfort in patients using BiPAP.

Innovative strategies and approaches focusing on patient factors affecting PAP adherence include motivational interviewing, motivational enhancement, telemedicine and desensitization techniques.

Motivational interviews and enhancement

Motivational interviewing and motivational enhancement were first used to help with alcohol abuse.17 Motivational interviewing is goal-oriented, patient-centered counseling to elicit a particular behavioral change. The goal is to explore and resolve ambivalence, increase engagement, and evoke a positive response and perspective that builds momentum and results in action.

Motivational enhancement and motivational engagement in the use of PAP therapy were evaluated in the Patient Engagement Study.18 Patients were assigned to usual care (n = 85,358) or active patient engagement (APE) (n = 42,679). Usual care involved diagnosis of apnea, initiation of CPAP and follow-up, whereas APE included daily feedback (i.e., daily scores of apnea–hypopnea index, mask leaks, hours used), positive praise messages and personal coaching assistance. Overall adherence for patients assigned to APE was 87% compared with 70% in the usual-care group. The hours of use per night also increased for patients in the APE group.

The Best Apnea Interventions for Research trial randomized patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease (N = 169) to CPAP alone or CPAP with motivational enhancements for six months.19 Motivational enhancements and interventions included brief in-person and phone interventions. An overall average difference of 99 minutes per night improvement in CPAP use was reported in the motivational enhancement group compared with CPAP alone.

The Motivational Interviewing Nurse Therapy study trained nurses in motivational interviewing and randomized 106 patients with newly diagnosed OSA to CPAP alone or CPAP plus motivational interviews.20 Motivational interviews involved three sessions: one to build motivation prior to the CPAP titration, one to strengthen the commitment to achieve the prescribed time, and a booster session one month after CPAP setup. Adherence was found to improve at one, two and three months in the motivational interview group; however, no difference between the two groups in adherence was noted at 12 months.

Telemedicine

The role of telemedicine in improving adherence with CPAP therapy was evaluated in 75 patients with moderate to severe apnea randomized to APAP alone or with phone call support from a research coordinator.21 Phone calls occurred two days after device setup, and daily monitoring of several factors was done via modem. Patients were contacted if the mask was leaking more than 30% of the night, use was less than four hours per night on two consecutive nights, the apnea–hypopnea index was greater than 10, or the average pressure needed was higher than 16 cm of water. Statistically significant improvement was found in the telemedicine group in mean adherence, minutes used per day and mean amount of time spent with the patients.

Desensitization to PAP therapy

Case scenario #6. A 33-year-old woman with a history of anxiety and depression and a remote history of abuse as a child was diagnosed with severe apnea. When she tries to use her CPAP, she has a sense of panic and cannot proceed.

Which of the following has NOT been shown to be beneficial in this situation?

Answer: Short-acting hypnotics.

The short-acting hypnotic zaleplon (Sonata) was evaluated in a one-month study of 88 patients compared with placebo control, and no difference was found between the two groups in measures of adherence to therapy or symptoms.22

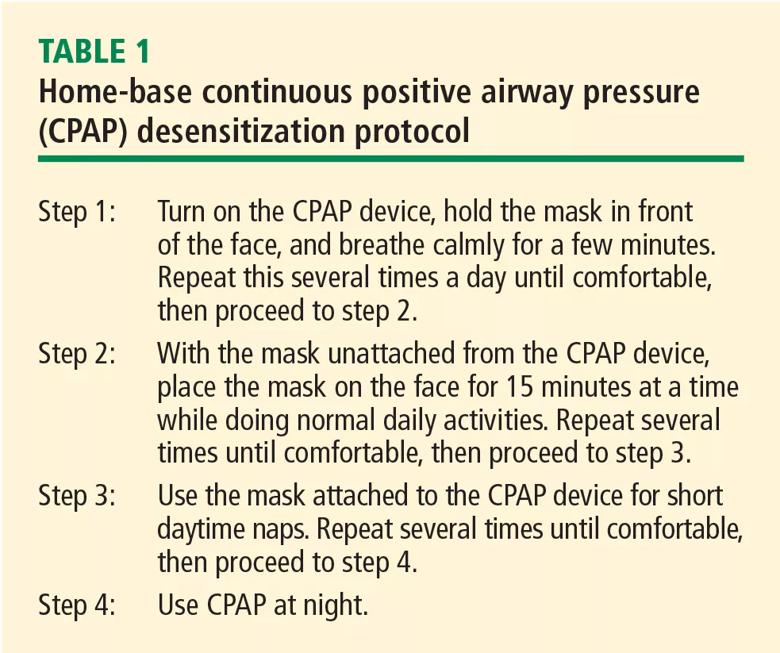

A protocol for desensitization to CPAP use is helpful to assist patients in acclimating to therapy. An example of the steps in a desensitization protocol that patients can do at home is provided in Table 1.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7906c44e-8b59-4e66-bc10-af0dd6e2d697/CCJM_32tbl1_jpg)

PAP NAP. For some people, at-home desensitization is not enough, and a sleep lab session may be needed. A PAP NAP is a daytime study conducted in the sleep lab. Patients do not necessarily sleep, but work with a technologist with a minimal hookup to polysomnography equipment on mask desensitization as well as biofeedback techniques. PAP NAPs are indicated for patients with claustrophobia, anxiety surrounding PAP therapy or pressure intolerance.

A study of 99 patients with moderate to severe apnea and insomnia and concomitant psychiatric disorders resistant to CPAP evaluated adherence in a group receiving a PAP NAP (n = 39) compared with a control group (n = 60).23 The PAP NAP group had marked improvement in completion of CPAP titration in the lab, filling the CPAP prescription and using CPAP more than five days a week and more than four hours a night.

A new innovative concept called the Sleep Apnea Patient-Centered Outcomes Network is a collaborative group that includes patients, researchers and clinicians.24 The group addresses issues such as cost, outcomes and value in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea. A patient-centered website provides forums, education and data collection capability for researchers (myapnea.org).

PAP therapy is the gold standard for treatment of patients with moderate to severe OSA, though poor adherence to PAP therapy is a persistent problem. Advanced features in PAP devices such as APAP and other innovative strategies like motivational enhancement, desensitization protocols and PAP NAP are being used to address poor adherence. More randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate PAP for sleep apnea.

Note: This article originally was published in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2019 September;86(9 suppl 1):26-33).

Advertisement

Study shows comparable success rates to tongue base dependent epiglottic collapse

Screening tool helps flag conditions that warrant further attention

Patients with epilepsy should be screened for sleep issues

A deep dive into the evolution of surgical sleep therapy

Cleveland Clinic study finds that durable weight loss is key to health benefits

Novel procedures provide options for patients who can’t tolerate CPAP

Large cohort study suggests need for routine sleep screening as part of neurological care

A review of conservative, pressure-based and surgical treatments for OSA