Results demonstrate need for better adherence to practice guidelines

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/eb3aa555-06e1-4eae-a769-6194d0c42b58/22-HNI-3211321-CQD-Hero-650x450-1_jpg)

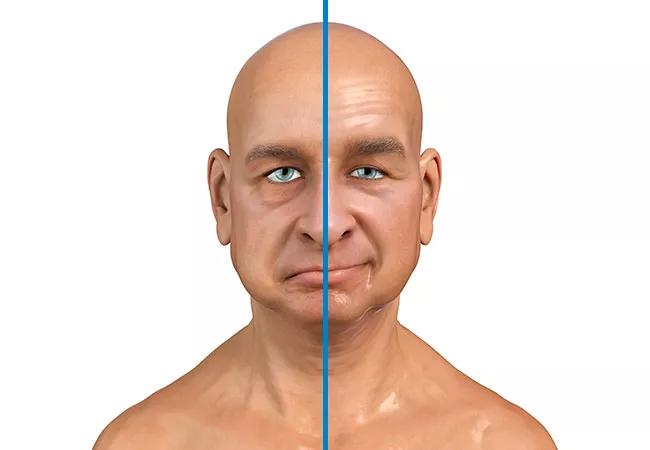

Bell's palsy

The most common single nerve disorder, Bell’s palsy (BP), presents as partial or complete facial paralysis and can be associated with additional symptoms including hyperacusis, epiphora, dysgeusia, facial numbness or pain, oral incompetence and dysarthria. The exact cause of BP isn’t known, but the evidence suggests that reactivation of a dormant viral infection can cause the facial nerve to swell and become inflamed.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

BP varies in severity from mild to severe and usually resolves without intervention within three weeks of symptom onset. Complete recovery is usually achieved within three to six months. However, some studies have found that 30% of BP patients do not recover fully and experience residual facial paralysis, asymmetry or synkinesis.

When people seek medical care for BP at an emergency department or primary care facility, they may see providers with little or no experience with this uncommon condition. Patients with severe or persistent BP may be referred for evaluation by a specialist, such as a neurologist, head and neck surgeon, or facial and reconstructive surgeon.

At the Cleveland Clinic Head and Neck Institute, clinicians were seeing BP patients “months or years after initial onset of their symptoms without having had proper follow up with a facial nerve specialist,” says Peter Ciolek, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Head and Neck Institute.

This prompted the Institute to conduct a large retrospective study of BP patients to learn their presentation, management, referral pattern and outcomes. The findings were presented at the American Academy of Otolaryngology (AAO) 2022 annual meeting.

The study investigators used the 2013 American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) BP clinical practice guidelines as the standard of care. The guidelines strongly recommend a 10-day course of corticosteroid therapy at a high dose (50 mg prednisone for 10 days or 60 mg prednisone for 5 days followed by 5-day taper), ideally initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset for BP patients 16 and older. Oral antiviral therapy may be prescribed in combination with steroids but not as monotherapy.

Advertisement

Additionally, the AAO-HNS guidelines advise that patients who do not demonstrate spontaneous and complete recovery within three months should be referred to Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (FPRS) and closely followed. For the 30% of patients who do not fully recover, treatment options include non-surgical therapies such neuromodulator (botox) injections and facial retraining therapy, and surgical therapies including selective neuromyectomy, depressor anguli oris resection, nerve transfer procedures and gracilis free flap.

The investigators conducted a retrospective chart review on a cohort of 903 Clinic patients: 687 (76.1%) who presented to ED, 87 (9.6%) to internal medicine, 77 (8.5%) to family medicine and 52 (5.8%) to urgent care. On initial presentation, 759 patients (84.1%) had incomplete paralysis and 144 (15.9%) had complete paralysis; 114 patients (12.6%) had a prior history of BP.

Regarding treatment, 804 patients (89.0%) were treated with steroids and 592 (65.6%) were prescribed antiviral therapy, with 700 (77.5%) receiving a course of steroids lasting less than 10 days while 203 (22.5%) received a course of at least 10 days. Of those patients, 177 (19.6%) received appropriate duration and dosage of steroid therapy and 123 (13.6%) received both appropriate steroid therapy and antiviral therapy (combination therapy).

Eye involvement in BP has not been well defined in the literature but it is associated with drooping upper eyelid (lagophthalmos). Eye care was provided to 580 patients (64.2%).

Advertisement

Imaging (CT or MRI brain) was included in the workup of 491 patients (54.4%). Subspecialty referrals were made to Neurology (286 patients, 31.7%), Ophthalmology (97, 10.7%), physical therapy (36, 4%), and FPRS and/or Otolaryngology (51, 5.6%).

Regarding outcomes, 283 patients (31.3%) had complete resolution and 197 (21.8%) incomplete resolution, 62 (6.9%) had persistent palsy without improvement, and 361 (40.0%) were lost to follow up. A small number, 17 patients (1.9%), underwent surgical intervention.

The results demonstrated that only 15.5% of patients received medical therapy in accordance with AAO-HNSF clinical practice guidelines, consisting of adequate corticosteroid dosing in combination with antiviral medication. Regarding clinical settings, 31.2% of patients presenting to family medicine received appropriate medical therapy per the guidelines compared to 17% of patients presenting to the ED. “The majority of patients did not receive the standard of care for acute onset Bell’s palsy. All patients should have a 10-day course of steroids, unless contraindicated by another underlying medical disorder,” says Dr. Ciolek.

Since most BP cases can be diagnosed based on patient history and physical examination, the AAO-HNSF guidelines strongly discourage diagnostic imaging for acute onset, uncomplicated BP, less than the more than one half of study participants (54.4%) who had imaging.

As a result of these findings, the investigators are planning to “create better systems and protocols to ensure that patients are getting adequate therapy. We plan to establish system-wide care pathways to help guide our primary care colleagues in the proper management of acute onset Bell’s palsy,” says Dr. Ciolek.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Analysis of HNSCC patients shows HPV status to be predictive of higher abundance of oncobacteria within the tumor

Case study illustrates the potential of a dual-subspecialist approach

Evidence-based recommendations for balancing cancer control with quality of life

Study shows no negative impact for individuals with better contralateral ear performance

HNS device offers new solution for those struggling with CPAP

Patient with cerebral palsy undergoes life-saving tumor resection

Specialists are increasingly relying on otolaryngologists for evaluation and treatment of the complex condition

Detailed surgical process uncovers extensive middle ear damage causing severe pain and pressure.