Clinical cohort study helps define red flags for these rare MS mimics

Adult-onset genetic leukodystrophies should be part of the differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS), and leading red flags include progressive gait and other neurological symptoms, negative oligoclonal bands and atypical white matter lesions.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

That’s the conclusion of investigators who conducted one of the largest-ever clinical cohort studies of the prevalence of genetic leukodystrophies initially misdiagnosed as MS. The study was presented at the virtual ACTRIMS 2021 Forum in late February by researchers with Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris, and Hotel Dieu de France in Beirut.

“MS misdiagnosis is widespread, with approximately 20% to 30% of initial diagnoses ultimately proving to be misdiagnoses,” says the study’s presenter and lead author, Alise Carlson, MD, a Cleveland Clinic neurology resident and future fellow with the Mellen Center. “MS misdiagnosis carries a number of deleterious consequences, including unnecessary exposure to immunosuppressive therapies, psychosocial and economic stress on patients, and stress on healthcare systems.”

Dr. Carlson notes that about 2% to 4% of patients misdiagnosed with MS are eventually diagnosed with genetic white matter disease, or genetic leukodsytrophies. “Because adult-onset genetic leukodystrophies are relatively rare, they pose a diagnostic challenge,” she says. “That’s particularly the case because most literature regarding misdiagnosis of these disorders are case reports or are focused on just one specific condition. Literature descriptions of diagnostic red flags for genetic leukodystrophies are extremely limited.”

To help fill that evidence gap, Dr. Carlson and colleagues identified all patients who were seen at Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center from January 2000 to August 2019 for possible MS and later were referred for genetic evaluation and/or had a genetic diagnosis documented in the electronic health record. Of 413 such patients, 19 individuals met the study’s inclusion criteria — i.e., genetic disease confirmed by single-gene testing, panel sequencing or exome sequencing.

Advertisement

Retrospective chart review showed that these 19 patients had the following collective profile:

These patients’ initial suspected MS clinical categories were as follows:

Most of the 19 patients had a progressive symptomatology rather than a subacute or relapsing-remitting course. The most frequent symptoms over the course of the patients’ disease were as follows:

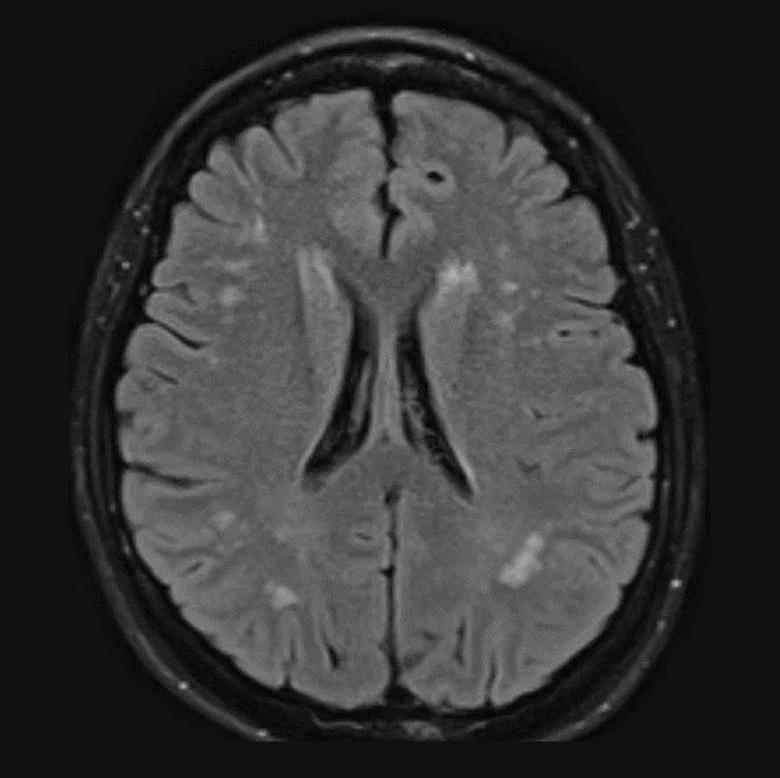

Atypical white matter lesions were common, most often characterized as multifocal (37%) or confluent (37%) but sometimes solitary or absent (26%) and occasionally contrast-enhancing (11%). Although some lesions suggested MS, more often they were atypical.

Oligoclonal bands were present in only two patients (11%).

All but five of the 19 patients had been started on treatment for MS — corticosteroids in 10 patients and disease-modifying therapy in four patients.

After genetic testing, the following genetic diagnoses were most common among the 19 patients:

Advertisement

The remaining six patients all had distinct genetic leukodystrophies with different causative genes.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/18f192b4-03c4-494e-a87f-94d6c79a7fea/21-NEU-2070733_CQD-inset_805x805_jpg)

MRI from one of the study patients who was ultimately determined to have hereditary spastic paraplegia linked to a c.1777A>T/c.1777A>T mutation in the SPG7 gene. Note the multiple scattered, discrete T2/FLAIR hyperintense lesions in the subcortical and periventricular white matter.

“When MS diagnostic criteria are applied inappropriately to patients with atypical clinical presentations, the pretest diagnostic probability decreases, which raises the risk for diagnostic error,” says co-investigator Jeffrey Cohen, MD, Director of the Experimental Therapeutics Program in Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center and also President of ACTRIMS. “In the case of patients who actually have a genetic leukodystrophy, misdiagnosis means delayed opportunities for genetic counseling and appropriate therapy in addition to potential harm from inappropriate therapies.”

“Our findings underscore the need to include adult-onset genetic leukodystrophies in the differential diagnosis of MS,” adds Dr. Carlson. “Suspicion for these disorders should be raised when an atypical presentation is accompanied by progressive neurologic symptoms — particularly gait symptoms — with negative oligoclonal bands and atypical white matter lesions. Yet there are always nuances, as oligoclonal bands are occasionally seen in genetic white matter disease and are therefore not 100% specific for MS.”

The researchers call for more comprehensive characterization of the clinical and imaging features of genetic leukodystrophies misdiagnosed as MS, noting that Cleveland Clinic is participating in a multicenter study to better characterize a larger cohort of these rare patients.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Study identifies Ketorolac as a potential repurposable drug

The relationship between MTHFR variants and thrombosis risk is a complex issue, but current evidence points to no association between the most common variants and an elevated risk

One-time infusion of adenovirus-based therapy is designed to restore heart muscle function

Cleveland Clinic researchers receive $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health

New Cleveland Clinic fellowship fosters expertise in the genetics of epilepsy

Integrates genetic and clinical data to distinguish from GEFS+ and milder epilepsies

First-of-kind study aims to enable prevention of brain disorders before symptoms appear

Advanced genomic research techniques show potential to treat a variety of conditions