Research examines risk factors for mortality

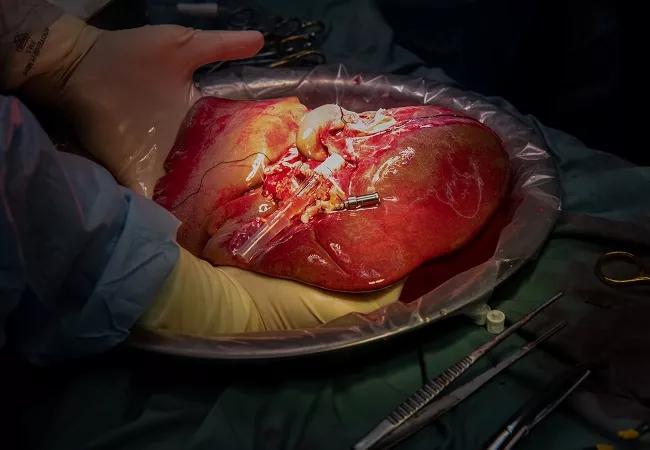

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6a1659ca-9762-4eca-a80c-50f2058a585a/22-DDI-3192632-Risk-factors-for-posttransplant-mortality-in-ACLF-650x450-1_jpg)

DDI 300384 Radigan 05-19-22

Patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), even those with advanced-grade disease and circulatory failure requiring multiple vasopressors, can achieve one-year survival rates exceeding 80% following liver transplantation, a large North American multicenter study including Cleveland Clinic researchers has found. The preliminary results indicate that transplants should not automatically be ruled out for ACLF patients needing moderate vasopressor support.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

However, the presence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in patients with ACLF grade 3 is associated with significantly reduced post-transplantation survival, the investigators found, prompting them to advise caution when considering whether to transplant in those cases.

“ACLF is a relatively newly recognized distinct clinical syndrome,” notes study coauthor Christina Lindenmeyer, MD, a transplant hepatologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. “Recent analysis suggests that patients with advanced-grade ACLF may have a higher mortality even than that of patients with acute liver failure, which is a more well-recognized clinical phenomenon associated with very high mortality. However, patients with acute liver failure receive special prioritization for liver transplantation, whereas critically ill patients with ACLF do not receive the equivalent waitlist designation.”

ACLF occurs in patients with decompensated cirrhosis (symptomology of ascites, variceal hemorrhage and/or hepatic encephalopathy) and is associated with severe systemic inflammation and organ failure. Its prevalence is rising nationally and internationally. ACLF severity is indicated by assigning one of three grades based on the number of failing organs, with grades 2 and 3 associated with increasing mortality. Liver and renal failure occur most often, followed by coagulation, brain, circulatory and respiratory failure.

Liver transplantation is the only lifesaving intervention for ACLF. Transplant has established survival benefits, although previous studies showed patients with ACLF-3 at the time of transplant had the lowest one-year survival rates. Those studies did not address several potential survival impactors, including the level of vasopressor dosages in patients with circulatory failure at the time of transplant and the presence of PVT.

Advertisement

To address these knowledge gaps regarding the risk factors for post-transplantation mortality among patients with ACLF, the Multi-Organ Dysfunction and Evaluation for Liver Transplantation (MODEL) Consortium was formed. As a part of this research effort, Dr. Lindenmeyer and colleagues analyzed transplant outcomes data to determine how various risk factors, especially PVT, impact survival among patients with ACLF-3.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed data from 10 centers in the United States and Canada. Their review included patients who underwent a liver transplant between 2018 and 2019 and who required care in the intensive care unit prior to transplantation.

The European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) criteria was used to identify ACLF. Of the 318 patients included in the analysis, 106 (33.3%) had no ACLF, 61 (19.1%) had ACLF-1, 74 (23.2%) had ACLF-2, and 77 (24.2%) had ACLF-3 at transplantation.

Circulatory failure in the study population was defined as the need for vasopressor support on the day of transplant due to either a mean arterial pressure of <70 mm Hg or an indication of hypotension. Patients with ACLF-3 who developed circulatory failure were grouped by whether their vasopressor dosage at transplant was moderate or low; moderate was defined as a norepinephrine infusion of >0.10 mcg/kg/minute.

A diagnosis of PVT in the study population was based on the most recent ultrasound or contrast-enhanced imaging before transplant. The researchers collected detailed information on the location and extent of the PVT, as well as treatment with anticoagulation.

Advertisement

Statistical analysis of outcomes data showed that the survival probability one year after liver transplantation was significantly higher among patients without ACLF (94.3%) compared with patients with the condition (87.3%). But one-year survival rates were similar across the three ACLF grades: ACLF-1 (88.5%), ACLF-2 (87.8%), and ACLF-3 (85.7%).

One-year survival rates also were relatively comparable among ACLF-3 patients with and without circulatory failure (82.3% vs. 89.6% respectively). Of the 29 patients with ACLF-3 who needed vasopressor therapy at the time of transplant, 24 (82.8%) survived at least one year. Sixteen of the ACLF-3 patients treated with vasopressors were receiving a moderate dose at transplant; 13 were on a low dose. The researchers observed a significantly lower survival rate among ACLF-3 patients with PVT at the time of transplant compared with no PVT (57.1% vs. 91.9%). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed a significant association between PVT and one-year post-transplant mortality. The researchers found no notable survival differences based on location or size of a patient’s PVT or whether a patient was treated with anticoagulants prior to transplant.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that patients with ACLF of all grades have a good probability of surviving at least one year after transplant, including those with ACLF-3.

These data also suggest that patients with ACLF-3 potentially can undergo safe transplantation even when multiple vasopressors are required prior to surgery, according to the study authors. However, Dr. Lindenmeyer and her colleagues note that the decision to proceed with liver transplantation ultimately should be based on clinical judgment and experience.

Advertisement

Additionally, this research sheds light on the association between PVT and significantly reduced post-transplant survival among individuals with ACLF-3. While caution is warranted, Dr. Lindenmeyer does not believe the presence of PVT should inevitably preclude patients from transplantation.

“This is a finding that we as a transplant team need to be aware of, particularly in this critically ill patient population,” she says. “These patients may be at higher risk than patients without ACLF and we need to be prepared with pre-determined strategies to reduce the risk associated with portal vein thrombosis in the operating room and then postoperatively.”

Regarding the similar survival rates for all grades of ACLF, Dr. Lindenmeyer acknowledged there are limitations to the research that must be recognized, including the potential for selection bias. “While the MODEL consortium offers granular, center-specific data, the analysis is retrospective,” she says. “So we were limited in our ability to analyze the less objective day-to-day factors that may impact center-specific transplant candidacy selection.

“The patients who get transplanted with ACLF-3 are our best critically ill candidates,” she says. “They are typically the patients who, for a variety of reasons, objectively or subjectively, are determined to have a higher likelihood of survival on the other side of transplant.”

This potential selection bias, according to Dr. Lindenmeyer, is why additional prospective research is critical to understand how patients are selected and what their survival probabilities are in the short and long term. The MODEL consortium hopes to better define and produce data that will help drive future prospective study.

Advertisement

“As hepatologists, we are all patient advocates,” Dr. Lindenmeyer says. “We don’t want to lose our patients, but we also want to provide them with meaningful quality of life after transplant. We hope to apply the information that we’re learning from these series of studies to better guide conversations in the intensive care unit with patients and their families.”

Another goal of the MODEL consortium is to educate providers and drive ACLF-specific protocols both pre- and post-transplant to optimize survival in this patient population. Dr. Lindenmeyer and her team recently opened enrollment for a prospective trial that is part of the CHANCE study, an international, multicenter research effort. As one of the flagship study sites in the U.S., Cleveland Clinic will be at the forefront of gathering data to help guide protocols and policy for liver transplantation among ACLF patients.

Advertisement

Enhanced visualization and dexterity enable safer, more precise procedures and lead to better patient outcomes

Minimally invasive approach, peri- and postoperative protocols reduce risk and recovery time for these rare, magnanimous two-time donors

Patient receives liver transplant and a new lease on life

New research shows dramatic reduction in waitlist times with new technology

Cleveland Clinic study shows positive outcomes for donors and recipients

Program's approach maximizes donor safety without compromising recipients' outcomes

Program expands as data continues to show improved outcomes

Atypical cells discovered after primary sclerosing cholangitis diagnosis