Approach could help clinicians identify patients at an increased risk of progression who could benefit from more aggressive treatment

A recent, multi-institution, collaborative research effort suggests that, when compared with traditional clinicopathologic models, genomic risk stratification offers superior prediction of clinical outcomes in patients with soft tissue leiomyosarcomas (LMS). Additionally, the findings—published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research—showed that this approach is comparable to traditional models when used in uterine LMS.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Leiomyosarcoma, both soft tissue and uterine, is a relatively common sarcoma type and comes with a poor prognosis,” says study author Josephine Dermawan, MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Diagnostics Institute, Cleveland Clinic. “A key aspect of managing these cases is risk stratification to better understand which patients may progress and could potentially benefit from a more aggressive treatment approach.”

“Currently, however, we only use clinicopathologic criteria to risk stratify these patients,” she explains. “We have more and more cancer types today that undergo comprehensive molecular profiling. And so, we are interested in exploring if we can use genomic parameters to come up with a different way to risk stratify LMS tumors and determine how it compares to traditional methods.”

Dr. Dermawan and colleagues performed comprehensive genomic profiling in a cohort of 195 patients with soft tissue LMS (151 primary at presentation) as well as a control group of 238 patients with uterine LMS (177 primary at presentation). The analysis included at least one year of follow-up.

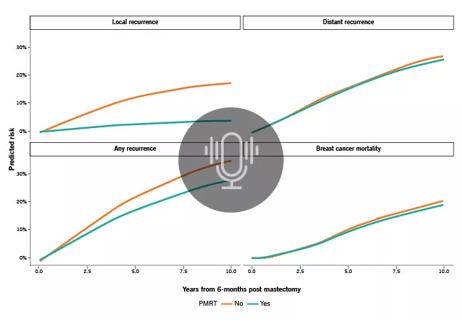

Data showed that the French Federation of Cancer Centers grade, but not tumor size, predicted progression-free survival (PFS) or disease-specific survival (DSS) in the soft tissue LMS cohort. Comparatively, tumor size, mitotic rate and necrosis were associated with inferior PFS and DSS among patients with uterine LMS.

In soft tissue LMS, researchers found that a three-tier genomic risk stratification performed well for DSS. This model is as follows: high risk (co-occurrence of RB1 mutation and chr12q deletion (del12q)/ATRX mutation), intermediate risk (presence of RB1 mutation, ATRX mutation or del12q), and low risk (lack of RB1 mutation, ATRX mutation or del12q). “The ability of RB1 and ATRX alterations to stratify soft tissue LMS was validated in an external AACR GENIE cohort,” according to Dr. Dermawan and colleagues.

Advertisement

For the uterine LMS cohort, a three-tier genomic risk stratification was significant for both PFS and DSS—high risk (concurrentTP53 mutation and chr20q amplification/ATRX mutations), intermediate risk (presence of TP53mutation, ATRX mutation or amp20q), and low risk (lack of any of these three alterations).

Through longitudinal sequencing, the researchers determined that the majority of molecular alterations were early clonal events that continued during disease progression.

“Our study showed that the performance of genomic risk stratification and traditional, clinicopathologic risk stratification is comparable in uterine leiomyosarcoma,” says Dr. Dermawan. “However, our research also suggests that, for soft tissue leiomyosarcoma, genomic risk stratification may do a better job in risk stratifying tumors compared to traditional clinicopathologic criteria.”

When discussing these conclusions, Dr. Dermawan cautions that long-term and external validation is still needed. “We are excited to see if this can be reproduced by other investigators and if this approach will be used more broadly in the future,” she notes. Moving forward, the researcher team is conducting related studies, particularly in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma.

Today, genomic testing of these tumors remains variable, depending largely on access. “While this testing modality is not necessarily available to everyone, it is becoming much more commonplace than even five years ago,” says Dr. Dermawan. “We hope that our study will offer new insights for oncologists and, when its feasible and not cost-prohibitive, they can perform genomic testing to further inform how they risk stratify patients’ disease.”

Advertisement

“Cancer treatment is always a multidisciplinary effort,” notes Dr. Dermawan. “As a pathologist, I encourage oncologists to always talk to us regarding their cases, and the more communication, the better. Sometimes just reading the report itself may not necessarily convey all the nuances regarding a case. And the same goes for research studies. Multidisciplinary collaboration is where the best outcomes and research comes from.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Genetic variants exist irrespective of family history or other contributing factors

Use of GLP-1s and improving cardiovascular health lowers risk of hematologic malignancies

Slower drug elimination from the body among females may impact safety and efficacy

Integrated program addresses growing need for comprehensive cancer care among adolescents, young adults and adults under 50 with early onset cancers

Study demonstrates potential for improving access

Gene editing technology offers promise for treating multiple myeloma and other hematologic malignancies, as well as solid tumors

Optimized models can personalize predictions for patients with prostate, breast and other cancers