Two major trials promise key progress against the last unaddressed major risk factor

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/996c5449-8e98-472c-ae10-284ff874f865/22-HVI-3411464_GLP-1-and-GIP-dual-agonism_650x450_jpg)

22-HVI-3411464_GLP-1-and-GIP-dual-agonism_650x450

Researchers and clinicians have long recognized a web of cause-and-effect relationships within the triad of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes and obesity. Diabetes promotes development of CVD, and at least two classes of diabetes medications have been shown to improve CVD outcomes in patients with diabetes. Likewise, obesity raises the risk of type 2 diabetes, and randomized trial evidence shows that substantial weight loss in people with obesity can reverse diabetes or reduce its risk of development.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

As for the third part of the triad — between obesity and CVD — a contributory role has been well established, with mounting data now indicating that excess body weight’s association with CVD risk seems to be independent of its promotion of individual risk factors such as hypertension. Yet the “effect” aspect in this part of the triad has been more elusive. Growing evidence from observational studies indicates that treatment of obesity with bariatric surgery improves cardiovascular outcomes, but these findings have not been confirmed in randomized trials, largely because of randomization challenges with bariatric surgery.

But now the quest for randomized evidence of CVD benefits from treating obesity may soon yield dividends, thanks to two major multicenter trials of anti-obesity medications — one run by the Cleveland Clinic Coordinating Center for Clinical Research (C5Research) and one with a Cleveland Clinic cardiologist as co-principal investigator. This article profiles these trials and their implications for management of CVD in people with obesity after briefly tracing the path to the launch of these studies.

The past several decades have been boom times for innovation across multiple CVD risk factors, bringing forth an abundance of medications to regulate lipids, control blood pressure, lower blood sugar and improve inflammation. Yet one leading risk factor — obesity — has been largely untouched by this innovation wave. In this absence of therapeutic advances, the proliferation of societal factors that promote weight gain has left the United States with a 41.9% prevalence of obesity and a 73.9% prevalence of overweight or obesity among its adult population, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Advertisement

“While we make progress on all these other CVD risk factors, obesity has continued unabated,” says A. Michael Lincoff, MD. “We don’t have nonsurgical therapies that directly target cardiovascular risk-associated overweight or obesity and the related metabolic abnormalities. The profile of a typical heart disease patient has shifted over the past 30 years from the hypertensive, chain-smoking, type A personality to someone with overweight or obesity and concomitant diabetes. We can treat some of that latter patient’s risk factors, but there’s still much risk associated with body weight that we cannot directly target with medical therapy beyond lifestyle changes.”

The “medical therapy” caveat in Dr. Lincoff’s comment is important, as the growth and refinement of bariatric (metabolic) surgery over the past 30 years has resulted in significant gains for many patients, not just in life span and quality of life but also in reversal of diabetes and reduction of diabetes risk — as well as compelling evidence suggesting cardiovascular benefits.

A good deal of that cardiovascular evidence has come from Cleveland Clinic researchers. A Cleveland Clinic team led by cardiologist Amgad Mentias, MD, recently published a large database analysis showing that bariatric surgery in Medicare enrollees with obesity was associated with lower risk of mortality, new-onset heart failure and myocardial infarction (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1429-1437).

Additionally, Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Steven Nissen, MD, has worked with bariatric surgeon Ali Aminian, MD, to publish a series of large retrospective cohort studies examining the effects of bariatric surgery on various clinical outcomes. Most notable is a study of cardiovascular outcomes among 2,287 patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity who underwent bariatric surgery at Cleveland Clinic and 11,435 matched controls (JAMA. 2019;322:1271-1282). The analysis showed that metabolic surgery significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events over 3.9 years of follow-up, with a hazard ratio of 0.61. The same researchers found similar effects on cardiovascular events from bariatric surgery in patients with obesity and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (JAMA. 2021;326:2031-2042).

Advertisement

“The average weight loss with sleeve gastrectomy, a common bariatric surgical procedure, is 20% to 25%,” says Dr. Nissen, Chief Academic Officer of Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute. “We wanted to see if losing 20% or more of body weight would have a major effect on mortality, cardiovascular morbidity and other forms of morbidity. And it certainly did.”

Nevertheless, bariatric surgery — although low-risk — is a highly invasive procedure that a limited number of patients are willing or able to consider. Even if all potential candidates chose to pursue it, their sheer numbers would swamp surgical capacity for many years to come. “We need pharmacological help to address the extraordinary effects and reach of the obesity epidemic,” Dr. Nissen says.

Yet the track record of anti-obesity medications to date has been “uniformly disappointing,” notes Dr. Lincoff, in terms of their effects on cardiovascular outcomes, their safety profiles or both.

However, around the time that bariatric surgery’s positive effects on diabetes and cardiovascular outcomes were emerging from observational studies, researchers were taking note of the weight-loss and cardiovascular effects of the GLP-1 receptor agonist medications (GLP-1 RAs) used to treat type 2 diabetes.

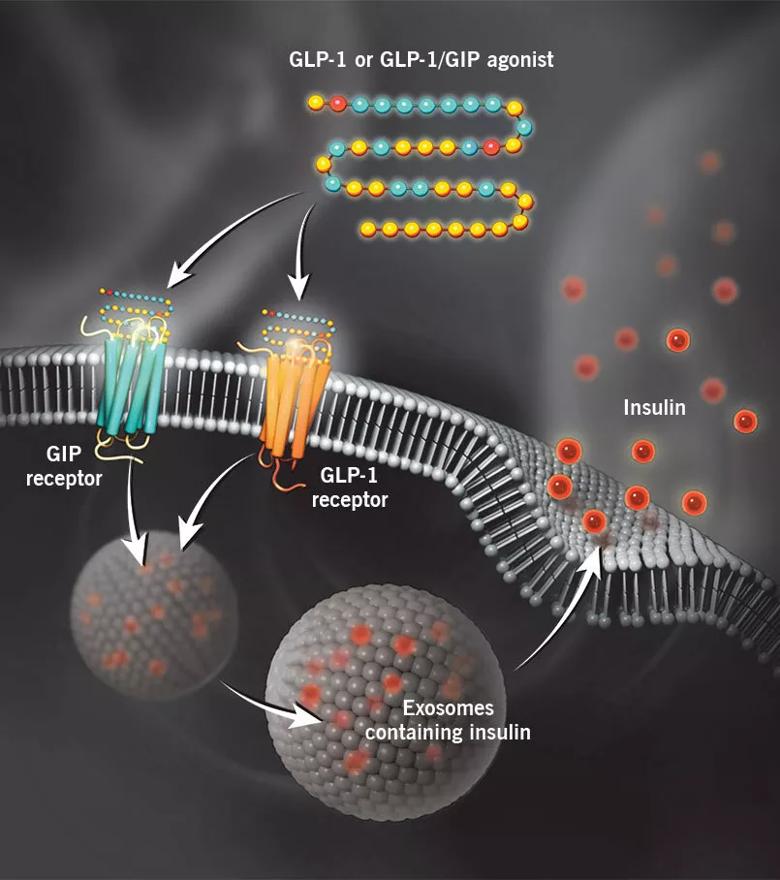

GLP-1 stands for glucagon-like peptide-1, a gut hormone released in response to eating that serves as a satiety signal, stimulating insulin release, inhibiting glucagon secretion and regulating gastric emptying.

Consistent with these effects, GLP-1 RAs have been associated with substantial weight loss in clinical trials, leading to FDA approval of two of these agents — liraglutide and semaglutide — for chronic weight management in adults with obesity or with overweight and at least one weight-related comorbidity. “Semaglutide, which is the most potent pure GLP-1 RA available, has produced weight loss of up to 17% to 20% in clinical trials designed to assess its effect on weight,” says Dr. Lincoff.

Advertisement

GLP-1 also produces effects that promise cardiovascular benefit, such as natriuresis, diuresis, and reduction of blood pressure and inflammation. Accordingly, GLP-1 RAs have reduced the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in a number of randomized outcomes trials in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, no completed trial has examined the effect of GLP-1 RAs on cardiovascular events in patients with established CVD and overweight/obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes.

That will change when results of the phase 3 randomized SELECT trial (NCT03574597) are released, perhaps as soon as 2023 or early 2024. This multicenter study is enrolling 17,500 adults aged 45 or older with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2 or greater and established CVD but without diabetes. Patients are randomized to 2.5 to 5 years of weekly semaglutide injections or placebo as an adjunct to standard care. The primary outcome measure is time to first major adverse cardiovascular event.

“The SELECT trial is designed to fill the gap of randomized trial evidence on cardiovascular outcomes with treatment of overweight or obesity independent of the effect that semaglutide has on diabetes,” says Dr. Lincoff, who serves as co-principal investigator of the study.

As the SELECT trial nears completion, a similar large trial was launched in autumn 2022, but this one involves a new wrinkle on GLP-1 receptor agonism that appears to yield even greater weight loss. It comes in the form of tirzepatide, a medication approved by the FDA in May 2022 to treat type 2 diabetes. Tirzepatide is the first in a class of drugs called dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists that activate the receptor for another gut hormone, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), in addition to the GLP-1 receptor.

Advertisement

With this dual agonism, tirzepatide has demonstrated the largest weight loss in a randomized trial of any medication for obesity/overweight to date, with its highest dose achieving a 22.5% reduction relative to placebo at 72 weeks in the phase 3 SURMOUNT-1 trial (N Engl J Med. 2022;387:205-216). Submission of the drug for FDA approval for weight loss is expected after completion of a second phase 3 trial, SURMOUNT-2, in spring 2023.

Notably, SURMOUNT-1, which excluded patients with diabetes, showed improvements with tirzepatide in all prespecified cardiometabolic measures. That, together with the Cleveland Clinic studies showing cardiovascular outcome benefits from bariatric surgery, prompted Dr. Nissen to help initiate the launch of the SURMOUNT-MMO trial (NCT05556512) in October 2022 (“MMO” stands for “Morbidity and Mortality in Obesity”).

This phase 3 multicenter study, which is coordinated by Cleveland Clinic’s C5Research academic research organization, is enrolling 15,000 adults with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥ 27) who do not have diabetes but do have either established CVD or multiple CVD risk factors. Patients are randomized in parallel fashion to subcutaneous tirzepatide once weekly or matching placebo. The primary outcome measure is time to first major cardiovascular event over five years of follow-up.

Dr. Nissen, who serves as study co-chair of SURMOUNT-MMO, notes that the exclusion of patients with diabetes will avoid confounding of results by favorable outcomes due to tirzepatide’s antidiabetic effects. “If this trial is successful, we will have the evidence necessary to show the medical community that obesity is a reversible risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and other outcomes,” he says.

He adds that SURMOUNT-MMO is also worth watching for a number of its secondary outcomes, including time to onset of type 2 diabetes, renal death or end-stage renal disease, and a variety of quality-of-life measures.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/aaa456fe-fe16-4a7a-8446-c6f1a83181fe/22-HVI-3411464-Inset_GLP-1-and-GIP-dual-agonism_jpg)

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and GLP-1 receptor/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor dual agonists bind to their respective receptors on pancreatic beta cells to stimulate glucose-induced insulin secretion. In addition to enhancing insulin secretion, binding to these receptors and downstream signaling slow gastric emptying and reduce appetite, leading to weight loss.

Dr. Nissen expects tirzepatide to soon join the pure GLP-1 RAs with an FDA-approved indication for weight loss in addition to diabetes, although it may meet the same payer reluctance around reimbursement for weight loss that the pure GLP-1 RAs have. But Drs. Nissen and Lincoff suspect that reluctance will erode over time as more of these types of medications get approved for weight loss, particularly if the SELECT and SURMOUNT-MMO trials result in indications for atherosclerotic CVD.

“It’s going to be very hard for people not to accept the value of these drugs, particularly tirzepatide and future dual agonists, if we show they reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” says Dr. Nissen. “Tirzepatide produced weight loss at 72 weeks in the range of bariatric surgery, so a case can be made that this will be a cost-effective therapy. It may take time to convince payers, but it will happen. For the first time, I have hope that we can actually reverse the obesity epidemic.”

Dr. Lincoff is also optimistic, but he notes that cardiologists will need to gain familiarity with using the GLP-1 RAs and tirzepatide. “These drugs require dose titration, particularly to reduce adverse effects like nausea and diarrhea that are common soon after starting therapy,” he says. “So cardiologists will need to counsel patients through that and acclimate them to giving these drugs by subcutaneous injection.”

His colleague Dennis Bruemmer, MD, PhD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Cardiometabolic Health, already has considerable experience using these drugs for diabetes and weight loss. He says cardiologists will become increasingly comfortable using GLP-1 RAs and dual agonists, although they need to take care when starting them in patients with diabetes who are taking insulin. “In those cases,” he says, “cardiologists may need help from a physician specializing in diabetes, because the insulin dose will require adjustment and management becomes more complicated.”

Dr. Bruemmer notes that the medications are well accepted by patients. “These drugs are so powerful, and the injections and side effects compare so favorably with the invasiveness of bariatric surgery, that I think they will significantly reduce demand for bariatric surgery in the coming years,” he predicts.

Despite the promise of these new therapies to address all parts of the CVD/diabetes/obesity triad, approval and broad reimbursement for all these uses are likely still a few years off. What can be done in the interim for the tens of millions of Americans with CVD related to obesity or overweight?

That’s a question preventive cardiologists can find frustrating, for at least two reasons. First, the obesity epidemic fundamentally requires far more emphasis on prevention than on treatment. “We are reactive rather than proactive about this problem,” says Dr. Bruemmer, noting a range of contributors to obesity that are not proactively addressed, from societal factors to health system and payer factors. Second, many effective tools are available to manage obesity, but they are not widely used, for a variety of reasons. Dr. Bruemmer cites the example of medically supervised weight loss programs. “These can be quite effective,” he says, “but very few patients end up taking part,” for reasons that range from coverage and access challenges to inertia on the part of providers or patients.

Bariatric surgery is another effective tool, yet only a fraction of eligible patients undergo it. The reasons are multifactorial, but one key obstacle is limited access. While broader access is desired, Dr. Bruemmer cautions that bariatric surgery must be offered in a comprehensive way if it is to be safe and successful. “Patients need to be followed in a specialized bariatric surgery program,” he explains. “Their medications need to be titrated. They need to be on certain supplements to help with nutrition. They require monitoring on a number of fronts and careful, regular follow-up after surgery. This type of care from a high-volume center with a comprehensive program is the way to ensure good outcomes from bariatric surgery.”

The milestone NIH-funded Look AHEAD trial (N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145-154) found that intensive lifestyle intervention focused on weight loss did not reduce cardiovascular events in a large cohort of adults with overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes. Despite the reality that lifestyle change alone doesn’t adequately address these conditions in most individuals, Dr. Bruemmer says it’s an essential component of any ultimately successful treatment. That includes tirzepatide and the GLP-1 RAs.

“If patients start these medications without changing how they eat, the medications will be less effective,” Dr. Bruemmer says, “although they make it easier to eat less because they cause satiety. Initiation of these medications should always be accompanied by a nutrition session to instruct patients on portion sizes and other dietary issues.

“Regardless of any other treatments,” he concludes, “patients’ best chances for a long, healthy life are going to come with exercise and eating healthy.”

Advertisement

Initial data indicate tolerability and promising cardiac remodeling effects

LLM-driven system uses both structured and unstructured data, provides auditable justifications

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most