Researchers identify potential path to retaining chemo sensitivity

A Cleveland Clinic team dedicated to improving outcomes for patients with ovarian cancer (OC) has found a potentially promising new path for interrupting the process that makes OC cells resistant to platinum-based chemotherapy.

In a recent study published in Molecular Cancer, researchers describe important new discoveries about the CD55 protein, which is found on OC cell surfaces.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The new insights build on work from 2017, when researchers discovered that the CD55 protein on cell membranes is prominent in certain subsets of cancer cells, including ovarian cancer.

“This protein not only protects the cells (against cisplatin), but it also turns on a signaling network that activates or induces a cancer promotion pathway,” says Ofer Reizes, PhD, staff in the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Sciences at Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute and the Laura J. Fogarty Endowed Chair for Uterine Cancer Research. “If we block this protein on cancer cells, we block cancer progression. We block them from being resistant to chemotherapy.”

In ovarian and uterine cancers, gold standard treatment is debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy. No targeted approaches currently exist. That partially accounts for why epithelial ovarian cancer, one of the most common gynecologic malignancies, has an overall five-year survival rate of only 45%. The disease also has vague symptoms and tends to be diagnosed in advanced stages.

For a while, the investigators’ work on CD55 focused on cellular signaling control of cancer progression. “This protein has been studied for 30 or 40 years, not necessarily on cancer,” says Dr. Reizes. “But it had always been studied in the membrane.”

The break-through emerged when Rashmi Bharti and Goutam Dey, postdoctoral fellows studying OC samples, noticed that CD55 was also in nuclei, not just at cell surfaces.

“We started looking at ovarian and uterine cancer cells that were both chemo-resistant and chemo-sensitive. We discovered that if they are resistant, the protein was in the nucleus,” says Dr. Reizes. “If they were not resistant, there were lower amounts of the protein and a lower amount in the nucleus. We're finding that if this protein goes from the cell membrane into the nucleus, the cancer becomes more aggressive.”

Advertisement

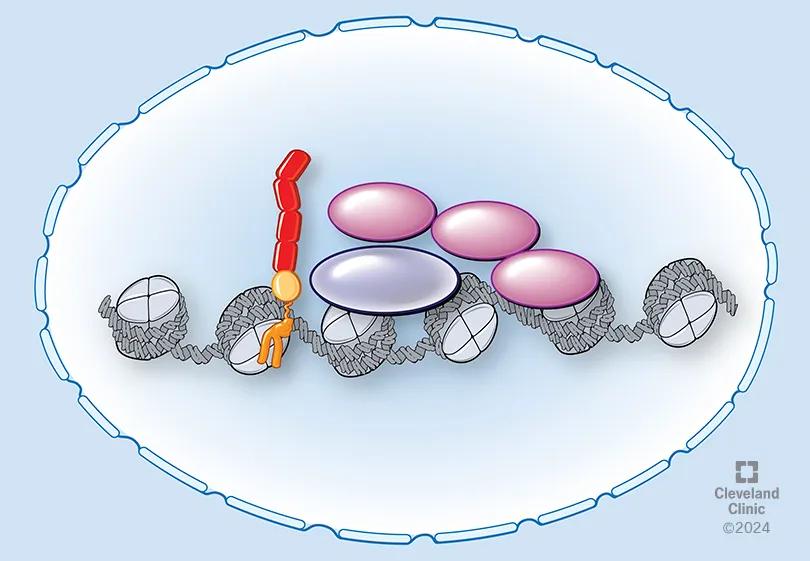

The investigators found that nuclear localization is driven by a trafficking code containing the serine/threonine (S/T) domain of CD55. Nuclear CD55 results in cisplatin resistance, stemness and cell proliferation in ovarian cancer cells. The S/T domain is necessary for nuclear entry. Deletion of the CD55 S/T domain is sufficient to sensitize chemo-resistant cells to cisplatin.

“We now have a hook,” says Dr. Reizes. “We have a path to identify ways to block this protein from going to the nucleus, but we need to find those molecules to block it. We have a patent at the moment on that process, but we need to show that we can actually do it.”

The team’s research is supported by Cleveland Clinic Innovations and a Catalyst Grant, which provide resources for the development of programs and technologies likely to have a positive impact on patients.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c3907bfd-8d34-43d1-8125-8b1cc559d8d5/Ovarian-CA_assets_2_24-LRI-4798611_CQD1)

CD55 interacts with ZMYND8 and PRC2 complex to modulate PRC2 target genes in ovarian cancer. (Illustration originally published in Molecular Cancer.)

Ovarian cancer relative treatability break down into three categories.

“When patients are platinum-sensitive, we can generally speak in terms of years between remission and a cancer coming back,” says Roberto Vargas, MD, a specialist in gynecologic oncology. “The drugs are able to give us meaningful responses and can even get us to a cure in some cases.

“Once platinum resistance sets in, for the most part we are speaking in terms of months between one treatment and another,” he adds. “We have a number of non-platinum chemotherapies, but their response rates are poor. A new class of drugs called antibody-drug conjugates have improved our ability to treat platinum-resistant disease. That said, the results from these drugs are still not comparable to the response we see in a platinum-sensitive tumor.”

Advertisement

The presence of nuclear CD55 may also hold potential as a biomarker for platinum-resistance, allowing patients to be stratified before starting chemotherapy, says Dr. Vargas.

“Currently, we give everybody the same chemotherapy, and for 80% of the patients it will work. Identifying the 20% who don't respond would allow us to be proactive with our treatment strategies,” he says. This might include alternative drugs and/or trial participation.

More analysis of tumor samples and associated treatment experience will be needed to establish nuclear CD55 as a platinum-resistance biomarker.

Positively early indicators should be interpreted with caution, but the nuclear CD55/OC discovery is giving the researchers a sense of optimism. Reducing or eliminating platinum resistance could “reshape our cancer treatment strategies,” Vargas says. “It could impact who gets platinum and when, as well as potentially allow us to prevent the cancer from developing resistance/adapting. The ability to keep a patient in the platinum-sensitive category would certainly be groundbreaking.”

Collaboration among departments feeds the progress, says Dr. Reizes.

“Our initial discovery was an ‘aha’ moment,” he says. “And then you keep digging and you realize, oh, this is more than an aha moment. This has the potential for really impacting patients. It’s very exciting, because my goal has always been to impact patients. I could be at some other place doing work, but being able to interact with our clinical colleagues, and then being able to answer questions with the tools that we have here — not every place has that.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Two blood tests improve risk in assessment after ovarian ultrasound

Robust research focuses on detection and prevention

Case highlights range of options for treating malignancies in pregnancy

Clinical trial to assess the value of nutritional, physical therapy and social supports prior to preoperative chemotherapy

Trial examines novel approach for a disease with a high mortality rate

A well-prepared team meets the distinctive needs of patients at hereditary high risk

Reassessing antibiotic dosage and type and restoring gut biome could improve survival rates

First full characterization of kidney microbiome unlocks potential to prevent kidney stones