Rare genetic disease diagnosed in a young woman – then two additional patients

By Elias Traboulsi, MD, MEd, and Meghan DeBenedictis, MS, LGC, MEd

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A woman one week shy of her 22nd birthday traveled 200 miles to seek a second opinion from Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute’s Retinal Dystrophy Clinic team. The patient had been evaluated elsewhere and was told she had either optic atrophy or a cone-rod dystrophy. She also had been informed that all of her genetic testing had been negative.

Upon receipt and review of her test results, we confirmed the negative results. However, we noted that the genetic testing she had undergone was neither thorough nor comprehensive for the clinical diagnoses in question. She had been tested for mutations in the OPA1 gene (which causes dominant optic atrophy), but did not undergo deletion/duplication array analysis, which accounts for up to 15 percent of cases. The cone dystrophy testing only included the CRX gene (which causes a dominant cone-rod dystrophy that is not consistent with her phenotype or family history) and select codons of the GUCY2D and the GUCA1A genes. This analysis did not include testing of the other 29 known cone-dystrophy genes. Thus, based on the testing she had received, both diagnoses were still possible and we recognized the need for further analysis.

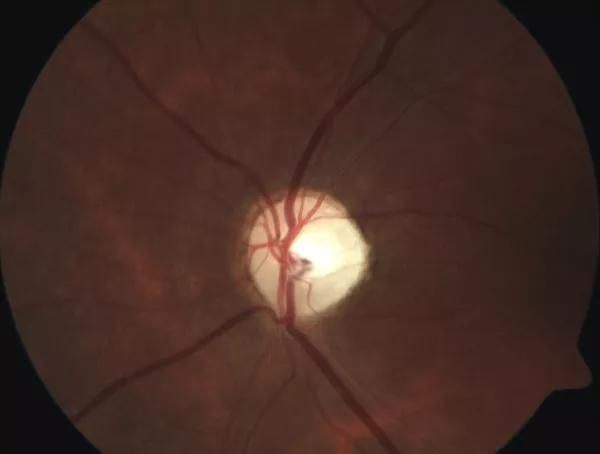

We followed our customary new-patient protocol — obtaining a detailed history of her visual symptoms; obtaining optical coherence tomography (OCT) images, fundus photos and fundus autofluorescence; and eliciting a family pedigree. OCT was significant for generalized atrophy. Fundus images and autofluorescence were normal. Her visual acuity was 20/25 OD and 20/40 OS, her visual fields were full to confrontation and she had a moderately abnormal score on color vision testing. Her family history was negative for vision loss.

Advertisement

The team also took the time to review the patient’s overall medical history, and it was through this questioning that we learned she also has type 1 diabetes, diagnosed when she was 7 years old. Upon review of her clinical data and discussion among team members, we determined that the most likely diagnosis for this patient was neither optic atrophy nor cone dystrophy. Instead, we were fairly certain she had a rare genetic disease called Wolfram syndrome.

Wolfram syndrome is an autosomal recessive condition due to mutations in the WFS1 gene that is characterized by juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, optic nerve atrophy and neurodegeneration with deafness. Diabetes mellitus is usually the first presenting sign, with optic atrophy following a few years later. Diabetes insipidus is present in up to 70 percent of patients. Additional symptoms include sensorineural hearing loss, loss of speech recognition, progressive neurological abnormalities (ataxia, dementia, psychiatric disturbance) and neurogenic bladder. The natural history and data from large patient cohorts affected by Wolfram syndrome are limited, with only 200 cases reported in the medical literature and an estimated prevalence of one in 500,000 people worldwide. We arranged genetic testing for this patient, and she was found to carry two heterozygous mutations in the WFS1 gene, consistent with the suspected clinical diagnosis. With molecular confirmation of Wolfram syndrome, the team was able to refer her to appropriate specialists for monitoring and treatment of Wolfram-associated complications.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/567301b5-3959-4db4-a7f4-237b77f560cb/17-EYE-1418-Traboulsi-CQD-Inset_jpg)

Atrophic and pale left optic nerve head in this patient with Wolfram syndrome.

It has now been four years since this patient was diagnosed, and she has graduated from college, is married and is doing well living with this condition. The systemic medical aspects of Wolfram syndrome are monitored and managed accordingly. Within one year of diagnosing this patient, we identified two additional patients with the same condition, highlighting the need for comprehensive diagnostic work-up and the value of a team approach to patient care in a subspecialty clinic.

Dr. Traboulsi is Vice Chair for Education and Director of the Center for Genetic Eye Diseases, where Ms. DeBenedictis is a certified genetic counselor.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

Treatment options range from tetracycline injections to fat repositioning and cheek lift