Active or damage and how to manage

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 56-year-old female with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) comes to see you for follow-up. She has had disease for nine years with past involvement of the sinuses, lungs, kidney and orbit. She describes sinus congestion and discolored drainage suspicious for infection. She has chronic periorbital pain and enophthalmos which are unchanged. Her visual acuity is normal which has not changed. In addition to starting her on antibiotics, you perform a CT sinus/orbit that shows sinus mucosal thickening and a left orbital lesion that are unchanged.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/8238c71f-65c5-4e98-b526-e146a0a8542d/18-RHE-1291-Langford-Figure-01-650pxl-width_jpg)

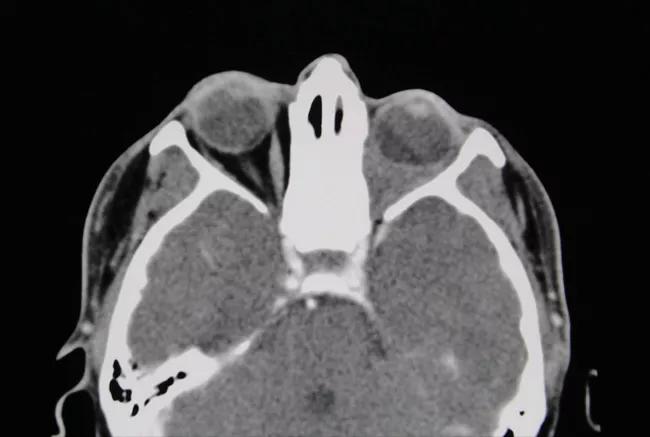

CT sinus/orbit shows a left orbital lesion that is filling the intraconal orbital space.

After completing the antibiotics, she is feeling improved and back to her baseline. Is there anything you should do for the orbital lesion?

A 46-year-old male with a three-year history of GPA comes to see you for follow-up. He has had past disease involving the sinus, lung, nerve and skin and has been in remission on methotrexate. At his follow-up visit, he comments on new pressure around his left eye with doubling of his vision when looking up and to the left. On exam, his left eye appears slightly more proptotic with restricted left eye movement on left lateral gaze. CT sinus/orbit shows chronic sinus mucosal thickening with erosion of the medial orbital wall and new soft tissue fullness along the extraconal orbital space abutting the medial rectus muscle.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1635b5b6-9579-4b8a-aec0-6e772fcddf39/18-RHE-1291-Langford-Figure-02-650pxl-width_jpg)

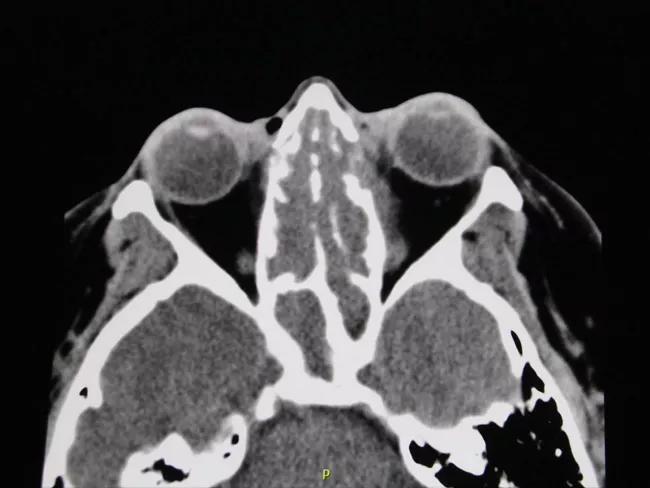

CT sinus/orbit shows sinus mucosal thickening with erosion of the medial orbital wall and soft tissue fullness extending into the left medial extraconal orbital space.

Advertisement

Is there anything you should do for the orbital lesion?

Orbital disease is among the most challenging disease manifestations of GPA. It can occur either de novo within the orbit or, most commonly, as a result of erosion of the lamina papyracea along the medial orbital wall, allowing inflammatory soft tissue to extend into the orbit from the sinus.

Presenting symptoms/signs of orbital disease can include pressure or pain in, around or behind the eye, as well as swelling of the eyelid or periorbital tissues. When the lesion abuts the ocular muscles, it can affect their function, resulting in disconjugate gaze and diplopia. Lesions adjacent to the optic nerve can impact vision. The optic nerve is particularly vulnerable at the orbital apex, where the nerve leaves the orbit and enters the intracranial space. Lesions in this location can also result in other oculomotor cranial neuropathies with corresponding clinical manifestations.

There are two key reasons why orbital lesions are challenging. The first of these is the anatomical construct of the orbit in being a confined, bony space. Inflammatory lesions within the orbit are close to structures vital to vision, such that even small lesions and any associated edema can have a profound impact. The second challenge is the rapid development of scarring that accompanies the inflammatory process and becomes permanent damage. This can result in chronic symptoms, signs and persistent radiologic changes. Over the course of time, scar tissue can retract, resulting in enophthalmos, which can also impact vision in some patients.

Advertisement

Treatment of orbital lesions is pursued with the goal of preventing progression and with the hope of halting inflammation that has not yet progressed to scar. The medications used for active orbital disease are the same as for other GPA manifestations and consist of glucocorticoids combined most commonly with rituximab, methotrexate or cyclophosphamide. Although some studies raised concern about the effectiveness of rituximab for orbital disease, others have supported benefit, reflecting the general difficulty in managing this manifestation. Orbital lesions can be particularly sensitive to changes in glucocorticoid dose, and some patients require long-term prednisone.

Surgery has limited if any role in management of orbital disease in GPA. Because of their composition of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts, orbital lesions can become adherent to adjacent structures. Surgical manipulation of lesions abutting the optic nerve can impact nerve function and result in vision loss. Because of this risk, surgery is almost always avoided in patients who have normal visual acuity.

Injecting glucocorticoids directly into the orbital lesion has no proven benefit, and radiation therapy has no role in treatment.

In the absence of other features of active GPA, determining whether to treat an orbital lesion is based on whether this is felt to reflect active inflammation or damage from scarring. This can be difficult to determine and is largely based on objective evidence from a careful ophthalmologic exam and changes in imaging. A persistent orbital lesion can occur as a result of damage from scarring and in the absence of growth is usually not an indication for treatment.

Advertisement

For patient 1 who had a known orbital lesion that had not changed, this was felt to reflect damage and treatment was not pursued. For patient 2, as there was development of a new orbital lesion, this was treated as active disease.

Orbital disease in GPA can be challenging for both patients and physicians. Effective management of these patients requires regular assessments by an ophthalmologist and intermittent imaging by CT or MRI, particularly in the setting of new symptoms. Preservation of visual acuity, minimizing chronic symptoms and avoiding treatment-related toxicity are the cardinal objectives, which can be achieved in many patients through careful multidisciplinary care.

Dr. Langford is Director of the Center for Vasculitis Research at Cleveland Clinic as well as Vice Chair for Research, Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being