Visual acuity goes from 20/200 and counting fingers to 20/40 and 20/60 after three doses

An 82-year-old patient presented to Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute with thyroid eye disease. Her visual acuity was 20/200 in the right eye and counting fingers at 3 feet in the left eye. Her left eye also had afferent pupillary defect with constriction of visual field.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

An outside ophthalmologist had been treating the patient’s condition with high-dose steroids — standard first-line therapy for thyroid eye disease with vision loss — but the condition appeared nonresponsive. In addition, an outside endocrinologist was managing the patient’s thyroid disease (Graves’ disease).

Although Graves’ disease can be related to thyroid eye disease, some patients have only mild Graves’ disease with no eye changes. Others have moderate eye disease, which can involve proptosis or eyelid retraction. Visual complaints in these patients are often due to dry eye. In severe cases, inflammation causes eye muscles to enlarge dramatically, compressing the optic nerve.

Thyroid eye disease is usually correlated with hyperthyroidism, but not always, says Cleveland Clinic orbital specialist and oculofacial plastic surgeon Catherine Hwang, MD.

“One type of thyroid eye disease occurs mostly in younger patients, who tend to have more eye retraction and dry eye,” she says. “That usually runs its course in 18-24 months, after which they may need decompression, eye muscle or eye lid surgery once the disease has stabilized. More serious, however, is the type that typically occurs in older patients or patients who smoke. There’s more muscle swelling in the eye, although not necessarily bulging. These are the patients we need to follow closely and need to treat swiftly if there is compression of the optic nerve, which can cause permanent vision loss.”

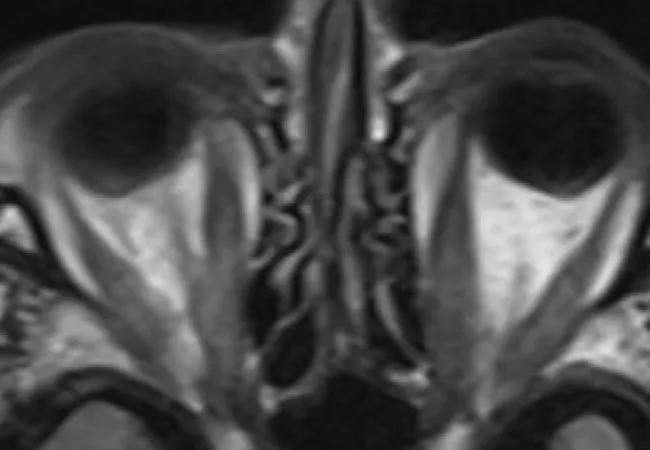

An MRI confirmed compression of nerves at the patient’s orbital apex. Since previous steroid treatment had not been effective at easing the compression, orbital decompression surgery was recommended.

Advertisement

“During surgery we open up the medial wall of the eye socket to create more space for the orbital contents so there’s less compression on the optic nerve,” says Dr. Hwang.

However, due to the patient’s personal preference and the COVID-19 pandemic, the patient refused surgery. Dr. Hwang then offered a new alternative treatment with teprotumumab (Tepezza®). Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in January 2020, teprotumumab is the first drug indicated for the treatment of thyroid eye disease.

“Initial studies of teprotumumab reported improvement in eye bulging, eye discomfort and other signs of thyroid eye disease, but not specifically in vision loss due to optic neuropathy,” says Dr. Hwang. “Even so, the patient was willing to try the drug as an alternative to surgery.”

Once approved by the patient’s insurance provider, intravenous infusions of teprotumumab began. Eight doses were prescribed, to be administered every three weeks at an infusion center. Dosage was based on patient weight: 10 mg/kg for the first dose and 20 mg/kg for doses 2-8.

While some patients experience nausea, muscle spasm and other adverse effects, this patient reported none.

After her third dose, the patient returned for a follow-up appointment with Dr. Hwang. The patient’s visual acuity had improved to 20/40 OD and 20/60 OS. Over the course of treatment, motility and proptosis improved and the inflammation around her eyes decreased.

Since completing all eight infusions, the patient’s vision is now 20/40 and 20/50 with resolution of the afferent pupillary defect.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cb73b77b-8449-4303-a2e9-8ae8642a231a/20-EYE-1934027-CQD-Thyroid-Eye-Disease-Case-Study-Inset-1_jpg)

Patient before teprotumumab (A) and after fifth infusion (B).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/80a84dc2-7b53-49d5-ac8e-fd4f8425889d/20-EYE-1934027-CQD-Thyroid-Eye-Disease-Case-Study-Inset-2_jpg)

MRI before teprotumumab (A,B) and after fifth infusion (C,D).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/986b0eca-3172-40d1-b906-3d5a7b15a642/20-EYE-1934027-CQD-Thyroid-Eye-Disease-Case-Study-Inset-3_jpg)

Visual fields before teprotumumab (A), after third infusion (B,D) and after fifth infusion (C,E).

Although teprotumumab is not indicated specifically for optic neuropathy in thyroid eye disease, the patient in this case has had dramatic improvement in vision with teprotumumab treatment.

“When there’s optic nerve involvement, surgery is the most direct and quickest way to resolve the issue,” says Dr. Hwang. “However, in patients who can’t or don’t want to undergo surgery, teprotumumab may be an alternative.”

Time to resolution is a concern, she adds. While surgery usually produces an immediate resolution, medication may take longer, especially if insurance approval is involved and medication can’t be started right away. The patient noticed improvement in her vision after the second infusion of teprotumumab, and the exam after her third infusion confirmed it. The patient has retained visual improvement after completion of the eight infusions (24 weeks).

“This patient was my first to try teprotumumab,” says Dr. Hwang. “Since then, other patients have undergone treatment and feel they are improved. Clinically, inflammation has dramatically decreased and we have seen improvement in proptosis and extraocular muscle motility. Some have reported side effects, including muscle spasms and fatigue, but none bothersome enough to stop treatment.”

Teprotumumab has been studied in active thyroid eye disease with high inflammatory scores and may be beneficial in patients with optic neuropathy. More studies are needed to determine the spectrum of patients with thyroid eye disease that would benefit from this new therapy.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

Treatment options range from tetracycline injections to fat repositioning and cheek lift